14 Criteria

Description

Criteria can be understood in a variety of ways. The dictionary definition of the term is one way we typically use it. Using criteria in a scientific manner is another way. In addition, there is the philosophical notion. I will start this essay with a general introduction of the term criteria. Then, I will start to explain the philosophical use of criteria. I will do this by explaining Wittgenstein’s notion of criteria. Hereafter, I will discuss the three C’s from Philosophy For Dummies. Finally, I will put the criteria into practice by analyzing some positions in the debate about international students in the Netherlands.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines the term criterion (the singular of criteria) as a standard by which you judge, decide about, or deal with something. In our daily lives, we apply criteria frequently. We judge things based on criteria, and we judge them continuously throughout the day. Even if you’re not aware of it, for example, when you see a chair, you use criteria to determine that it is a chair. Does it have legs? Does it have a surface to sit on? Does it have a back? We also need criteria in our interactions with other human beings. Certain roles in life have criteria. For example, when looking for a job, you will come across different criteria that need to be met by the applicant. Assignments and tasks also have criteria. Another example would be a school assignment. To pass the assignment, you need to meet the criteria that your teacher has set.

The term criterion in philosophy is usually associated with Ludwig Wittgenstein. I will explain his use of the term by referring to Lars Hertzberg’s work.

In his earlier works, Wittgenstein barely mentions the term criteria. It is in his later works that criteria become important. Hertzberg thinks that Wittgenstein used the term criteria to understand how a word is used. Questions like: ‘When do we say …?’, or ‘How does one tell …?’, or ‘What is meant by calling something …?’ are used to understand the use of a word. According to Hertzberg, Wittgenstein thought that the answers to these questions were criteria. Wittgenstein often asks, ‘What are the criteria for x?’ in his writings. Rather than supplying the answer himself, he seems to invite his reader to critically reflect on these questions.

Wittgenstein’s criteria are connected to the use of language and different practices. The term ‘practices’ in Wittgenstein refers to the various ways in which words or sentences are used within specific contexts. These contexts could include games, conversations, professions, or cultural settings. Hertzberg argues that according to Wittgenstein, the meaning and grammar of words depend on the practices in which they are employed. Philosophical problems often arise when we overlook or misunderstand these practices. Hertzberg says that criteria are the grounds or evidence we accept for applying words within a practice. These criteria can include knowing, understanding, expecting, or having an opinion. Wittgenstein’s criteria are not fixed or universal. They vary based on the purpose and situation of language use. My main takeaway from Wittgenstein is that finding the right criteria begins with asking the right questions like: ‘When do we say …?’, or ‘How does one tell …?’, or ‘What is meant by calling something …?’

Before Wittgenstein, but especially after his publications, the use of criteria has been important to philosophy. Philosophers use criteria to define certain concepts and to assess arguments. Criteria are a tool for assessment. The Philosopher’s Toolkit explains that philosophical criteria are usually expressed as ‘if and only if’ statements (iff for short) or as ‘necessary and sufficient’ conditions. This would look something like this: An object is a square if and only if it has four corners. Having four corners is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for something to be a square. It is necessary because a square needs four corners. However, it is not sufficient because other shapes can have four corners without being a square. That all four sides, all four angles, and the diagonals are equal is a sufficient and necessary condition for a square. In general, it is important to understand the use of iff statements in philosophy.

A philosophical argument must satisfy the traditional logic requirements of validity and soundness. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, an argument is valid iff there is no possibility in which the premises are true and the conclusion is false. An argument is sound iff it is valid and all the premises are true.

Tom Morris, the author of Philosophy for Dummies, describes three criteria by which we should judge positions. They are as follows:

- Is the position coherent?

- Is the position complete?

- Is the position correct?

The first criterion questions whether the different components that make up the position are logically connected. A position is coherent if it is plausible and consistent. The second criterion takes into consideration whether every relevant aspect has been added. It also assesses possible blind spots. In short, the criterion of completeness assesses the overall scope of the argument. The third and final criterion is correctness. Here, the content of the position is under examination. Is what is said true? An example that satisfies all three criteria is the following argument:

premise 1: without gas my car will not run.

premise 2: my car does not have gas.

conclusion: my car will not run.

The three C’s are a unity for a reason. Correctness alone is not enough. You need to assess the Coherence and Completeness in order to have a good position. Correctness without completeness lacks the full scope of facts. Completeness and coherency are not enough because you need to assess the content of the position on correctness. And this goes for all possible options. If one of the three C’s is not satisfied, a position is not a good position. So, to conclude this section, you can, and should, use the three C’s to assess the positions you come across.

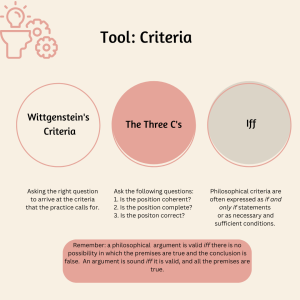

The above discussion offers some different ways of understanding and using criteria in philosophy. I have put these tools in an infographic to visualize them.

Application: Is the migration of international students to the Netherlands a problem?

The Netherlands has a high number of students, and this number has been rising for years. Nuffic observed that this year, the number has grown significantly less than in previous years however, seven percent as opposed to ten to twelve percent the years before. Quite a large part of this group consists of international students. The question is whether this rising number of international students is a problem. This topic is discussed in an article from Onderwijskennis.nl, which lays out the different positive and negative effects of internationalization among students. I will summarize this article and take a few of the positions to apply philosophical criteria to them.

The article approaches the internationalization of students on three levels: micro (students and university staff), meso (universities), and macro (society). I will first explain the positive effects.

Studying abroad can have a great effect on a student, according to research from Stebleton et al (2013). The Three International Competence Model from Nuffic reflects this:

- Intercultural competence: students have an open mindset and are interested in different perspectives. They respect diversity and can communicate in a different language. They can navigate different cultures and styles of communication.

- International orientation: students are familiar with international organizations and developments of their discipline. They use their international perspective to critically reflect on their social standing and those of others worldwide.

- Personal development: the student is more independent, creative, and able to adapt to different environments.

These skills can also be adopted by employees of educational institutions if they participate in internationalization activities. These skills will positively impact the students when they enter the job market after their studies.

There are many ways in which universities can profit from internationalization. International talent will positively impact the research quality at the university. This can happen through interaction with different research methods, for example. Partnerships with other universities can make teamwork easier as well.

Internationalization positively impacts society as well. Take brain gain and innovation in the Netherlands, for example. According to research from Elfferic (2022), one in four international students stays in the Netherlands for at least five years after graduating. These highly educated graduates contribute to the labor productivity and the international knowledge position of the Netherlands. According to CPB (2019), the Netherlands profits from international students as their presence in the country yields profit to the economy. Internationalization activities also promote open communication and active dialogue between countries. Understanding other cultures and perspectives plays a big role here.

All these points are important to take into account when discussing the growing number of international students in the Netherlands. There are, however, negative impacts as well. These will again be approached from a micro (students and employees), meso (universities), and macro (society) level.

Not everyone is able to study abroad. First-generation students, students with a lower socioeconomic background, students with children, and students with a migration background tend to miss out on these opportunities. It should not be the case that only an elite group of students can study abroad.

The negative aspects of the growing number of international students are much debated in the Netherlands. The main issues seem to be the limited number of available places at numerus fixus studies, student housing, and the quality of education. A study done by the Inspection of Education (2019) shows that there is no evidence to conclude that Dutch students are negatively impacted by the growing number of international students when it comes to the available places at numerus fixus studies.

The Netherlands has a tight housing market and more international students put pressure on the housing market. This can result in higher prices on the housing market in popular student cities like Groningen. Some students cannot find student housing once they have arrived in The Netherlands. In 2018 this problem was so big that hundreds of international students temporarily had to sleep in tents. A lot of international students experience rejection from possible housing because the tenants do not want internationals in their buildings. Some advertisements even say ‘no internationals’.

Universities started to offer more studies in English. This is a reason for the growing number of international students in the Netherlands. However, this shift in language can be a barrier for Dutch students. There are also worries that international students create a larger competition for numerus fixus studies. Yet, there is no hard evidence to back up these worries.

One of the societal concerns is inequality in the educational system. There can be certain obstacles to cooperation between different universities when it comes to inequality in resources, power, and knowledge. Wealthy countries attract the best students from poorer countries. So, another concern is that these wealthier countries with better job opportunities create brain drain in the poorer countries.

This article shows the many positive and negative aspects of the migration of international students. It is a great example of a thoroughly researched pro and con article. It sets out to investigate the most important positive and negative aspects of internationalization among students. Before diving into the three C’s I want to mention Wittgenstein. As he asked many times in his works: what is meant by calling…? This article starts with the question: what is meant by internationalization in education? and refers to a page where they give a definition that they use throughout the article. This goes to show that a criterion like clarity helps to find correct definitions (for more information about definitions check out entry 8). I will now set out to analyze this article using the three C’s.

There are two positions in this article, namely: internationalization of students has positive effects, and internationalization of students has negative effects. I will analyze both positions, and I will start with the positive position.

To analyze whether the positive position in this article is coherent, I have to check if there are any contradictions within the position. The position is organized at micro, meso, and macro levels. Each of these levels contains a few reasons why internationalization is positive. Namely: the personal developments for students who study abroad (these can also translate to university staff and Dutch students when implementing an international classroom). The university’s research and partnership with other universities would improve. The international students will enhance Dutch society through brain gain which improves labor productivity and the international knowledge position of The Netherlands. The Netherlands also profits financially from international students. None of these points are in contradiction with each other. The position seems complete because looking at the problem via the micro, meso, and macro levels helps to include most people that are involved in the situation. I think that the article should have included another group, namely the citizens of the cities that have a lot of student residents (Groningen, Leiden, and Amsterdam, for example). Another caveat I have when it comes to completeness is that it is not fully explained in the article how The Netherlands profits financially from international students. This specific issue has been a point of debate recently as well. However, the article does refer to a page that includes more information concerning this argument. Lastly, is the position correct? I would say yes. Each point is backed up by scientific research. It is important to fact-check your arguments and this article has done that very well. Therefore, the position in favor of internationalization of students satisfies the three C’s.

The position against consists of the same structure (micro, meso, macro). The position considers that not everyone can study abroad. It also considers the housing shortage and the quality of education. None of these points contradict each other or fail to logically relate to the position. I do not think, however, that the position is complete. This is because it fails to mention an important negative effect. The growing number of international students increases the workload of teachers at the university. Adding to that is the decrease in personal interaction between teachers and students. Since these topics are essential in the debate, this position in the article does not satisfy completeness. It does satisfy correctness, as the points that are mentioned are well-researched.

As explained before, a good position must satisfy all three C’s. Since the negative position does not satisfy all three C’s, it is not a good position. This article is not a debate, it gives insight into different reasons to be for or against internationalization. This could be a good resource for arguments that you can use in a debate.

To deepen the analysis given above, you could use Wittgenstein’s questions to arrive at criteria for each topic. For example: What does personal development for students who study abroad mean? What is a fair workload for university teachers?

Analyzing arguments, debates, and positions is an important skill in philosophy. Having the right tools to do that is essential. The three C’s are just one example of a set of criteria one can use. Understanding and creating criteria plays a big part in exercising that skill. Hopefully, this entry has shed some light on the use of criteria.

I have created a visual guide to accompany the philosophical tool criteria. In this guide, I have written down the three examples of criteria and their functions that are mentioned in this entry.

Philosophical Exercises

- Try to be like Wittgenstein in your thinking. Ask yourself the right questions to discover the criteria you need. The last section of this entry contains examples of this.

- Read the entry on definitions (entry 8) and reflect on the relationship between Wittgenstein’s criteria and definitions.

- As mentioned in this entry, the article discussed provides good resources for a debate about the increase of international students in the Netherlands. Get a group together to have a debate about this topic. Make sure to analyze any resources you use according to the three C’s.

References

- Baggini, J., & Fosl, P. S. (2010). The philosopher’s toolkit: a compendium of philosophical concepts and methods (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hertzberg, L. (2022). Wittgenstein on criteria and practices (Ser. Cambridge elements. elements in the philosophy of ludwig wittgenstein). Cambridge University Press.

- Morris, T. (2002). Filosofie voor Dummies (Pearson Education Benelux) Frontline, Nijmegen.

More information about international student migration in the Netherlands:

- This video from the NOS highlights more aspects in the debate: https://nos.nl/l/2438815

- https://www.adviesraadmigratie.nl/actueel/weblog/blogseries-en-commentaren/2023/internationale-studenten—de-belangrijkste-feiten-op-een-rij

- https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2022/11/40-procent-eerstejaars-universiteit-is-internationale-student