16 Philosophical Art

Bente Oost

Philosophers often put their ideas into words. They write essays or books, give lectures, and hold discussions to get their point across. These philosophical works often characterise themselves by their particular style and method: often, philosophers try to be very precise in the formulation of their arguments. However, even a very precise formulation may sometimes not suffice to get your point across. When this occurs, art may come in as an useful tool for doing philosophy. A thousand word description might sometimes be more easily understood in one picture. In other words: show, don’t tell.

What Does the Tool Entail?

Art can be used in many different ways as an extension of philosophy. Because of this, it is difficult to pinpoint exact characteristics of the tool. Roughly, two ways of application can be distinguished.

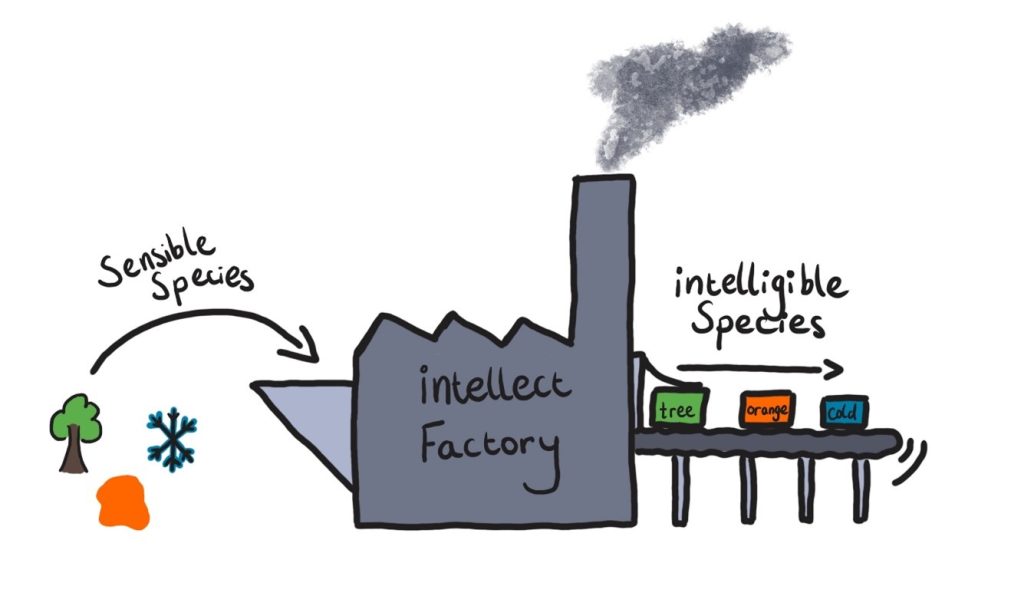

In the first way, artworks can be used in a clarificatory manner. Art can be used as a source of examples and illustration of philosophical arguments or concepts. A philosopher might reference an artwork in their work, or perhaps add the work itself, in order to get the reader to understand the point that is made. For example, below you can see an illustration that I made in order to explain Aquinas’ account of the intellect. By making such a drawing, Aquinas’ ideas become a lot more concrete to the reader, and I have to use significantly less words in order to get my point across.

Apart from using illustrations, one could also opt for applying certain artistic choices in one’s display of a certain position. A prime example of this would be Plato’s dialogues. Plato chooses a certain set-up, with certain characters, which has influence on how the point will get across to the reader.[1]

In the second way to apply this tool, the focus shifts from clarification to argumentation. Art can also be used to make an actual argument. For example, Martha Nussbaum and Richard Rorty find art and narrative literature beneficial to explore moral issues. The idea behind this is that a reader becomes more empathetic to others by reading about them in a narrative discourse, which will have more impact on their moral development than a list of rules to follow would have. In this way, the argument that someone wishes to make is communicated through the art itself. A novel can actually spread a message, and convince someone.

In this second way, I also consider artworks that try to raise questions about our point of view. These artworks do not always contain fully developed arguments, but can be easily developed into one. Take for example Magritte’s painting of a pipe, with the description “ceci n’est pas une pipe” (English: “this is not a pipe”). This painting raises questions about the notion of representation and experience: is what you see truly a pipe, or only a representation of that pipe? Merleau-Ponty interacted with these topics in the essay “Eye and Mind”, to which Magritte in turn responded to. Magritte’s painting caused a lot of philosophical debate.

Though the tool can be very useful to function as an extension of philosophy, it must be used wisely. Art can also make concepts, ideas or arguments more vague instead of concrete. It is therefore to be advised to carefully consider whether this tool will help to get your philosophical point across, or whether it will only complicate things.

How Can You Apply This Tool?

Should you have come to the conclusion that art will be useful for your philosophical endeavours, here are some steps to take in order to apply this tool:

- Determine in what way you wish to use art as an extension of philosophy.

Do you want to clarify a point or idea, or do you want to make an argument or propose a new idea? In this step, it might also be valuable to consider why just explaining your point in words will not be sufficient. This prevents the vagueness problem described above, but also makes you mindful of the goal of your application.

- Determine your medium.

When determining your medium, take into account the limitations of your own artistic abilities. You will not be able to communicate what you want in a medium in which you do not feel comfortable. In other words, find a medium that suits the purposes of your application, taking your own artistic abilities into account.

- Determine your audience.

Is your audience used to looking at art? Is your audience already familiar with the point you wish to make? These are questions to answer in this step, so that your end product comes to full fruition.

Once you have taken these three steps, all there is left is to use your philosophical and artistic abilities to make and present your artwork to the audience. Time to start showing!

A Problem

Should you wish to migrate to another country, you submit yourself to a complex process, with a lot of things that have to be organised. Depending on the nationality written in your passport, and on the location you wish to migrate to, this process can become very difficult, with loads of hurdles to jump.

A way to determine whether you have a passport that allows you to move relatively freely, you can consult the Henley Passport Index. This index gives points to the number of travel destinations you can visit without a visa, or where you can get a visa immediately upon arrival. In this way, it can determine the ‘best’ and the ‘worst’ passport out there. According to this index, the worst passport is that of Afghanistan. This country is all the way at the bottom of the list, at place 107. The best passport is given to people from Singapore. With this passport, you can access the most countries with minimal obstacles.

My home country, the Netherlands, is given a fourth place on this list. The topic of migration is always a controversial one during elections. The country struggles to house all migrants coming here, because of its population density. The Netherlands also characterises itself by its hefty bureaucracy: getting a permanent visa is no small feat. However, depending on your passport, this procedure can gain complexity. For example, migrating from Germany (which has the third place on the Henley Passport Index) to the Netherlands is relatively easy. According to the governmental website of the Netherlands, there are about twelve steps one must take before you can live in the Netherlands. For example, you have to open up a bank account, sign in to a municipality, get health insurance and change your driver’s licence. But should you wish to enter the same procedure from Afghanistan, the picture looks a lot different. According to the same website, migrating from Afghanistan to the Netherlands takes about 23 steps. Apart from the things a German must do, an Afghan also has to apply for a visa and residence permit, complete a criminal record declaration, and provide biometric data, to name just a few.

What passport you end up with is something what I believe to be something arbitrary. You are born in a place which leads you to having a certain booklet with a certain name on it. However, as I showed above, such an arbitrary matter of fate has a lot of effect on where you can move. This arbitrariness therefore frustrates me: your birthplace has too much effect on your ability to move around. Though this arbitrariness frustrates me, I also find it hard to encompass what it is like to experience migration having a ‘bad’ passport. I was gifted with the fourth best passport in the world. Therefore, it is difficult to understand the migration experience of someone from Afghanistan.

Thus, the problem I wish to present is twofold. Firstly, there seems to be a completely arbitrary element to your migration, which, secondly, causes an experience that I cannot grasp.

Applying Philosophical Art

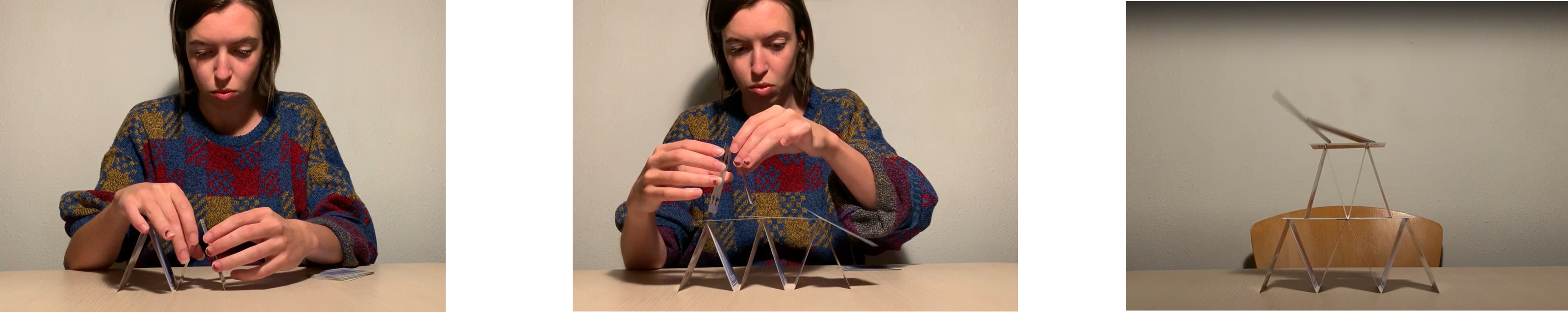

In order to address the problem presented above, I made performance art in which I built houses of cards. I performed my artwork twice, but with a different amount of cards. First, I made a house of cards that was three stories high. This first house represents the process of migration from Germany to the Netherlands. Building this house took approximately 25 minutes. Next, I made a house of cards that was double the size of the first one, in order to represent the doubling of steps one must take in order to migrate from Afghanistan to the Netherlands. This also took me more than double the amount of time I needed for the is first house. I captured my performance by making two photo series, which you can see below.

The artwork contains a lot of symbolic elements, some more literal than others. First of all, I chose to build houses, as when you are migrating, you wish to build a home. However, I did not choose to simply build a house, but specifically a house of cards. The cards are, just like passports, arbitrarily dealt. It is just a matter of luck whether you get a good hand. The cards also refer to the paper documents that are handled in the process of migrating to the Netherlands. The instability of the house hints again at the arbitrariness of the entire operation: one small mistake, and the entire house falls apart. There are no steady, well-founded foundations on which the house is built, but it is merely holding itself up with circumstances. Lastly, I chose specifically this kind of performance art, as the experience of building a house of cards creates stress and frustration. One must be patient in order to achieve it successfully. The process of migration has similar features.

When applying this tool, I used the same steps as described above. Let’s retrace the steps that I have taken in order to make my thought process more clear.

First, I had to decide what the purpose of my artwork was. Why did I need to make an artwork? The artwork that I created makes two arguments. First, it shows the arbitrariness of the passport you are given. Just one single name on a document is reason enough to have to build a house of cards that is twice as high. The artwork tries to show how strange this is, by taking the same elements but putting them in a different setting. By doing this, I hope to raise questions in the viewer: why would you want to build such a high house of cards? Why did you build two houses? The absence of the reason why argues for the arbitrariness of it all.

Secondly, by making this performance art, it allows primarily me, the artist, and secondarily, the audience, to grasp what it is like to migrate from one place to another based on a passport that is not originally yours. It allows me to experience a fraction of the stress, frustration, and length of the process. This would normally not be available to me. By empathising with the artist, the audience can also gain a glimpse into the experience of migration.

Especially the latter point justifies the usage of an artwork. Experience is not something that is easily put into words. An immigrant can tell their story using words, explaining the steps they had to take, and how long it took to complete the process, but it is not very likely that you will feel the same emotions as them when they tell you the story. In this artwork, the painfully long and frustrating process is actually experienced. Though it is only a symbolic version of migration, it still allows me to feel more emotions than if I were to merely read about a story of an immigrant.

The next step was to think about a medium. I have used two mediums, with the main medium being performance art. This medium was chosen because I believe it to be a very suitable medium in order to mimic experience. The artist has to act whilst making the art, thus experiencing simultaneously. As this was part of the problem I needed to tackle, performance art seemed like a sensible choice. In hindsight, I am quite content with this medium. I was certainly feeling frustrated and tense at times. Moreover, motivation started to decrease once the house had come down a couple of times. A lot of patience was required in order to complete the project. This was exactly what I had in mind.

Above, I advised to take into account your own artistic abilities. I did not have any previous experience with performance art, which made it a less attractive option. My knowledge about performance art before doing this project was rather limited. I was especially thinking about the performance artist Marina Abramović, who makes quite daring performance art, with a high level of discomfort. For example, she held on to a bow and arrow, with the arrow directed towards her heart. This was not the kind of performance art I saw myself making. However, by keeping the performance in itself quite simple, I did not feel uncomfortable in this medium. Building the houses of cards was not fun; it was never meant to be, but it was also not dangerous or very intense. Thus, even a medium that I did not have any experience in was still manageable in a form that suited my purposes.

The second medium I used was photography. This medium was used out of necessity, in order to be able to show you what I made during the performance itself. The photographs were thus just a practicality. I wanted them to show the process of what happened during the performance, with some additional information in the descriptions. A video would have been too long. The audience would have never seen the full video, therefore never seeing the complete experience. I therefore opted for a medium in which you could see more of the process.

For the last step in the process, I had to think about you, the audience. This step is a bit different in the current application under investigation, as you, the reader, are the audience. You do not merely see the artwork, but you are also able to access this explanation you are currently reading. This allows me to keep the art a bit vague, as I can explain a lot to you in the text around the art. If I did not have this option, I would have tried to incorporate the specific case more into the art itself, instead of only keeping it in the title of the art.

After completing all three steps, all that I had to do was make the art itself. This is not a step to take for granted, of course, but if you have done most of the thought process, you only need to execute! Below you can find two philosophical exercises that you can try to complete for yourself if you wish to try to make philosophical art. Best of luck!

Philosophical Exercises

- Seek out inspiration from other artists that have made artworks about migration. What is the message that they wish to show with their artworks? Do you agree with their choice of medium?

- Try to make an artwork yourself about the experience of migration. Personally, I find it easiest to start out with an artwork that explains a point already made, such as a small illustration. However, if you feel inspired to make something else, do not hold back! As all tools, it takes practice to get good at it.

Footnotes

[1] Rowe, pg. 10.

Bibliography

Rowe, Christopher. Plato and the Art of Philosophical Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. The Primacy of Perception. Edited by James M. Edie. Translated by Carleton Dallery. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1964. Revised by Michael Smith in The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader, Galen A. Johnson, ed., Evanston: Northwestern Univ. Press, 1993.

Asghari, Muhammad. “The Priority of Literature to Philosophy in Richard Rorty.” In Journal of Philsophical Investigations 13, no. 28, 2019.

Tate Museum, Migration and Art: Explore how Artists reflect on moving to new Places.