11 Principle of Charity

Femke de Rijk

Immigration and the Principle of Charity

The principle of charity has been a topic of philosophical discussion for decades. It is not about ethics, but rather about linguistic interpretation. There is no exact definition of the principle of charity, but at its core, the principle of charity entails that when there are different ways to interpret someone’s behavior or arguments, we should use the most favorable interpretation. In other words, we should be charitable to other people’s arguments, views, and/or behavior, even when the point of view from the other seems to contain errors or logical fallacies at first. The principle of charity does not require real charity, but rather a charitable way of interpreting (Dresner, 2011).

The principle has a long history, officially coined by Wilson (1959) in his work, Substances without Substrata. It was later redefined and developed by numerous philosophers such as Lewis (1974), Dennett (1982), and Quine (1960). However, the philosopher whose view on the charity principle has received the most attention is Davidson (1984a, 1984c, 1990). Davidson is a constructivist philosopher of communication, who believes that what something means linguistically is dependent on the way we interpret communication with others. He argues that interpreting others charitably is essential to achieving a shared understanding of a speaker’s beliefs and intentions.

According to Davidson, a key feature of the principle of charity is that we ascribe two things to others; (1) logicality and rationality and (2) the belief that the others’ beliefs are mostly true (Dresner, 2011).

In essence, this means that we should not immediately discard others’ views as irrational, but instead attempt to make sense of what they are saying. For example, when someone speaks in a way that we find hard to understand, we do not immediately think that they are stupid and that it is not worthwhile to figure out what they are saying. Instead, we try to understand them because we believe that it is worthwhile.

Dennet (2013) even takes this one step further. He says that we should try to improve others’ arguments so that we can criticize the best version of it (Dennet, 2013). This is often referred to as the steel man argument; we make the claim of others as strong as steel before criticizing it. This is the opposite of what we often tend to do. We often make a straw man version of other people’s arguments. This means that we make the opponent’s arguments seem weaker so that they are easier to knock over, just like a straw man. By making a steel man argument, we do not only try to understand what someone is saying when we don not understand them, but we also try to see why they speak so intelligibly. The aim is to find out the reasons for someone’s behavior so that we can understand them better. By discovering the reason behind their speech, we can avoid assuming that they’re irrational or stupid.

It is important to note that the principle of charity does not encourage us to simply accept all arguments. Rather, it aims to promote understanding and fairness, and decrease misunderstanding. According to Davidson, we can only disagree with one another when we also have a substantial background of agreement. This means that we should agree on many seemingly unimportant basic aspects of the world around us (Dresner, 2011). For example, when we see a table, chair, or whatever object, we must both linguistically agree that it is this specific object. Otherwise, the interpretation of the other is impossible. If we cannot understand each other, we can also not have disagreements. Yet, when we have a substantial background of agreement, we can have meaningful language and therefore, meaningful discussions (Dresner, 2011). One aspect of the Dutch society that can greatly benefit from a charitable interpretation is the interpretation of asylum seekers. This is what the next section will look at.

Application

‘Bus no longer stops at asylum center Budel after incidents’; ‘A growing number of suspicions crime against asylum seekers’; ‘Growing numbers of shoplifting by asylum seekers in ter Apel, regardless of increased measures’; ‘half of the citizens in Cranendonk no longer want an AZC in Budel’. These are just a few of the many headlines about asylum seekers in the Netherlands in the past years by the NOS (Dutch Broadcasting Foundation). The main story behind these headlines is that local citizens have made reports of theft, intimidation, and feelings of unsafeness, specifically around stations and public transport. In short, they tell us that asylum seekers in the Netherlands are causing trouble.

Most of the stories that the NOS posts are also posted on Facebook. If we take a look at the comment section of Facebook, we mostly see comments against asylum seekers. The most common comments are: ‘’there is only one solution; send them back to their own country’, ‘close the borders’, ‘They are ungrateful’, ’ They do not know how to behave’ or ‘This kind of behavior is to be expected’ and the list goes on. These points capture what is often believed to be the general view of Dutch citizens; asylum seekers are trouble and not welcome in the Netherlands.

This belief that this is the general view of asylum seekers can have a large impact on politics and policymaking because, in a democracy, policymakers try to implement policies that most people support. This can have an impact both on a local and national scale. This raises questions such as: is this view fair? are (all) asylum seekers only trouble? And should they be unwelcome here? Maybe even more importantly, does thinking about asylum seekers this way help us out of the problems we are experiencing with them? Is there maybe a better approach? Let us try the principle of charity.

Earlier in this chapter, we have learned from Davidson that a key feature of the principle of charity is that we ascribe two things to others; (1) logicality and rationality and (2) the belief that the others’ beliefs are mostly true (Dresner, 2011). In other words: we try to gain a shared understanding of a group, or persons, beliefs, and understandings. So how do we apply this to the general view of asylum seekers?

Well, firstly, we ascribe logically and rationally to asylum seekers as a group. This means that if a group of asylum seekers act in a way that is unacceptable in our culture, we do not immediately assume that they are ‘ungrateful’ or that ‘it is to be expected’. Rather, we try to gain an understanding of them – this starts with interpreting them to have logical and rational reasons to act in a certain manner. Secondly, we understand asylum seekers to have true beliefs and the things they say are mostly true. Hence when we ask them why they do something, we interpret them with the expectation that they answer with honesty.

Applying these two steps can help us widen our perspective, but it does require us to assume many things – we assume people to speak the truth and be logical and rational. But are there any reasons for us to believe these assumptions in the real world? Making a steel man can help us find these reasons.

Making a Steel Man

With the basics of rationality, logicality, and truthfulness, we can now try to go from a straw man to a steel man. To do so, we have to actively look for reasons against the general view that asylum seekers are unwanted. The key to building a steel man is asking questions and listening. This section will try to build an argument for asylum seekers as strong as steel by asking questions that go beyond our original scope, such as: what other news is there about asylum seekers? Or, are there things I don’t know about? Further investigation of the news can bring you to such headlines:

‘Asylum seekers in Goes are sick of it: pests, bad hygiene and cold’; ‘Asylum seekers emergency shelter Purmerend on a hunger strike, unrest in asylum reception grows’; ‘ ‘inhumane’: again a critical report on the shelter of asylum kids’. These are just a few of the many headlines by the NOS that report on the poor living conditions of asylum seekers in the Netherlands. In short, the headlines and the articles tell us one thing: the living standard of asylum seekers is very low. Through widening our perspectives, we increase our understanding of why asylum seekers are causing trouble. They are living with too many people in small rooms, in inhumane circumstances, and lack opportunities. Any human being would not be able to tolerate this for extended periods. By widening our perspectives, it suddenly makes much more sense why they are causing trouble, because it increases our understanding. This is how we can build a steel man and with this gain the ability to better understand the other.

Focusing on the Individual

In the previous section, I have focused on creating a steel man for the generalized perspective on asylum seekers. While it is relevant to change the general picture of asylum seekers for the reasons named above, it is unfair to only judge asylum seekers as a group. In any group, there is always a big range of behavior, and we cannot tar everyone with the same brush. Furthermore, it is individuals that we encounter in our everyday lives. Therefore, whatever we conclude about a group should not define our opinion about individuals: we should also apply the principle of charity to individuals. Now, how can we do this? That is what this section will investigate. I will do so via an example.

I will analyze an interview with asylum seeker Hijasul. In this interview, the principle of charity unfolds beautifully and it shows how we can simply apply this in our everyday lives. You can read the full interview here. I will only summarize the most important part of this article.

In short, Hijasul was born and raised in the safe country of India. He has a master’s degree in sociology and in 2015, he came to the Netherlands for his studies. This is when things went downhill. He got scammed by the company that arranged this. Now he is stuck in the Netherlands without a residence permit. He cannot leave, study, or work. He quickly ran out of money and started looking for an unregistered cleaning job. After some time, he found a job together with a woman. He thought she looked nice in her Facebook profile picture. When he met her, she wasn’t. She was moody, did not smile, was suspicious of him, and did not want him to touch anything without asking. She asked Hijasul to fold clothes, but he did not know how to do this. When she found out, she was annoyed and said that he had to stop and let her do it. After a little while, she asked what he was doing in Amsterdam. He told his story and she concluded ‘’You are really nice aren’t you?’’ and her attitude completely shifted. She was now friendly and understanding of why he couldn’t fold clothes. She told her life story and after this, Hijasul didn’t see her as a moody woman anymore. Rather, he understood her.

In this story, we can beautifully see the effects of being charitable. In the first part, the cleaning lady seems unkind, suspicious of Hijasul, and is frustrated when it turns out that he is not capable of doing the job well. From the very beginning, the lady was not being charitable. She made a straw man out of Hijasul, or at least, she was not being charitable. In her eyes, he was probably an untrustworthy refugee that she now had to share her money with. When it turned out that he was not good at his job, her straw man suspicions were, at least in part, confirmed. She could have stuck to this idea, like many people do. Rather, she did something else. By asking him the simple question of what he was doing in Amsterdam she applied the principle of charity without knowing. She tried to understand him.

When she asked him what he was doing in Amsterdam, she understood him to be rational, logical, and truthful and everything changed. She did not discard his behavior to be irrational but tried to make sense of why he was behaving this way. By asking questions, she started building a steel man. Together, they solidified it. They achieved a shared understanding of Hijasul’s beliefs and intentions. Her questions inspired him to do the same, which led them to build a steelman for her. With this, their understanding of each other grew. Their attitudes completely changed the situation: they went from disliking each other to liking each other.

Their story is not exceptional. There are many stories like this. What we can learn from this is that we should give every individual a chance, regardless of their image as a group. We can do so by asking them questions, listening to them, and trying to build a steel man together.

How Building a Steel Man Can Help Us

On a Generalized Level

Now, how can a steel man on a generalized level help us? Most importantly, it can help us find the source of the problem. Rather than concluding that there is a problem and trying to achieve the impossible: to get rid of it, we now grew an understanding that we can apply in the process of finding a realistic solution. This can help change decisions and policymaking on a national level. When stuck to a straw man built in the comment sections of Facebook, it is easy to believe that asylum seekers are trouble and that they should leave the country. If this is understood to be the main view of society, this can be harmful. When we put effort into building a steel man, we can make sense of why they are causing trouble. With this, we can have a better overview of the problem and how to solve it. If this can be adopted by more people and become more vocal in the media, politics and decision-making regarding asylum seekers may change, bringing us closer to a solution.

On a Personal Level

Now, how do we benefit from being charitable to individuals? Being charitable to individuals can help us in our everyday life and shift our perspective. Long-term, it can help change the generalized view of asylum seekers, but short-term, it can help our own relationship with asylum seekers. It can help us communicate with them and overcome unnecessary frustrations and biases, guide us to solutions in our personal lives rather than problems and create a better environment to live in for both asylum seekers and locals. A society based on understanding can bring us further than a society based on assumptions.

Conclusion

At the beginning of this chapter, I stated that Davidson believes that the principle of charity is about linguistic interpretation, not about ethics. Yet, in the process of writing this chapter, I have learned that it is near impossible to separate these two. When we try to understand someone charitably, ethics also come into play. The principle of charity is also about fairness, right or wrong, responsibility, and so on. While this piece has diverged from Davidson’s original intentions, I believe that the addition of morals can enhance his point. Taking everything together, the principle of charity encourages you to ask questions, listen to others, widen your perspective and try to understand others. One of the tools you can use for this is building a steel man. With the principle of charity, we can build a society based on understanding, which can bring us further than a society based on assumptions.

Philosophical Exercise

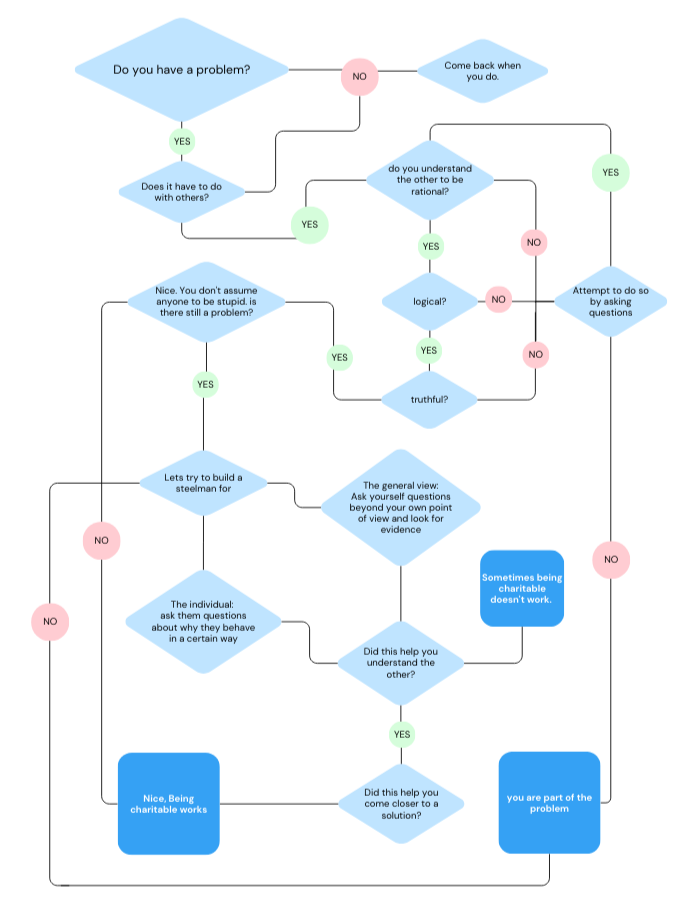

- You feel yourself being uncharitable towards an individual asylum seeker or to asylum seekers as a group. Follow this flow chart. It aims to make you think, be charitable and come closer to a solution. Did it work?

- Imagine a person that is strictly against asylum seekers on both a general and a personal level. Can you recognise ways in which they are being uncharitable? How could you get them to apply the principle of charity? And how can you both benefit from this application?

References

Davidson, D. (1984a). Radical translation. In D. Davidson, Inquiries into truth and interpretation (pp. 125–139). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Davidson, D. (1984c). Truth and meaning. In D. Davidson, Inquiries into truth and interpretation (pp. 17– 36). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Davidson, D. (1990). The structure and content of truth. Journal of Philosophy, 87, 279–328.

Dennett, D. (1982). Making sense of ourselves. In J. I. Biro & R. W. Shahan (Eds.), Mind, brain, and function: Essays in the philosophy of mind (pp. 63–81). Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Dennett, Daniel. 2013. Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking. New York: W. W. Norton Company

Dresner, E. (2011). The principle of charity and intercultural communication. International Journal of Communication, 5, 14.

Lewis, D. (1974). Radical interpretation. Synthese, 27, 331–344.

Quine, W. V. (1960). Word and object. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

The mind collection, 2023. #elephantintheroom [picture]. The mind collection. https://themindcollection.com/steelmanning-how-to-discover-the-truth-by-helping-your-opponent/

Vluchtverhalen (2017). Hijasul [photograph]. Vluchtverhalen. https://vluchtverhalen.nl/scherpe-randen-amsterdam/

Wilson, N. L. (1959). Substances without substrata. Review of Metaphysics, 12, 521–539.