6 Class Critique

Yihan WANG

Description

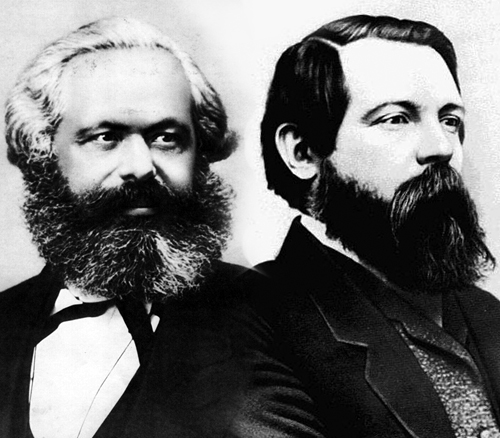

Class critique is a tool used to critique ideas and theories that serve the upper and ruling classes or exploit the lower classes. This critical approach was mainly developed by German philosophers, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the theory of Marxism.

In Marxism, society consists of a base and a superstructure. The base refers to a society’s mode of production, and the superstructure refers to relationships and ideas not directly related to production, such as culture, ideology, religion, and the political system. The classic Marxist view is that the economic base determines the superstructure. For Marx, class is an organizing principle of society and is formed by the ownership of the means of production. Building on the theory of Marxism, the Greek-French philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis stated that class should be determined more by control over production and exchange than by ownership. In Castoriadis’ theory, those with control give the orders and are the higher class, while the lower class can only accept and carry out the orders.

In distinguishing between different classes, the German philosopher Max Weber, who was heavily influenced by Marx, proposed status in relation to economic life, and status in society, and referred to the idea of social honour and prestige. It can be seen as a further addition to this view of Weber, and in relation to how class arises and perpetuates itself, the French philosopher Pierre Bourdieu proposed four types of capital.

He classifies capital into economic, social, cultural, and symbolic capital (Bourdieu, 1977). Economic capital refers to wealth, social capital refers to social connections and networks, cultural capital is represented by degrees awarded by schools and ceremonies, and symbolic capital refers to reputation and prestige. As a tool and measure for defining and distinguishing between different classes, these four types of capital can be transformed into each other, e.g., acquiring a higher degree by means of economic and social capital which translates into cultural capital. The continuation of the flow of these capitals in society cannot be separated from another of Bourdieu’s concepts, the Habitus, which is similar to habits. The process of people interacting and growing up in family and society is the process of forming and training the habitus. In this process, the different classes instil their habits and tendencies of thinking, reacting, mental activity and behaviour in the people of the class. People of higher classes control and set the rules of society, and thus, people of higher classes are more likely to adapt and succeed in an educational and social system that suits them better, while people of lower classes need to work harder while having fewer opportunities.

Lawford-Smith (2016) pointed out class privilege and the need to eliminate it. Most groups have a relative class advantage, only those in the lowest class do not. People from higher class may use the privilege that comes with this advantage to deliberately keep people at the bottom in the lowest social class. This may be in their interest and helps them continue to maintain their high class.

Class critique is primarily a reaction to social and political change. Any political ideals or philosophical theories related to this must consider the general social facts, circumstances and feasibility. According to Marxism, there are two main groups in society, capitalists and workers. Capitalists own and control the means of production, while workers have no control over the means of production but intend to strive for ownership of them. In modern societies, social hierarchies are being updated with more blurred boundaries. It is impractical to just distinguish the society by using capitalists and workers while the reality is more complex. It is therefore more feasible to distinguish between different classes by the accumulation of Bourdieu’s capital. On this basis, observing the system of the society’s functioning, its rules, government policies and regulations, ideas or political changes that appear to be fighting for the rights of the people can be formulated for the benefit of higher-class capitalists. These rights can benefit the higher classes and protect their status and interests, but they may also come at the expense of exploiting the interests of the lower classes or disadvantaged groups.

While applying a class critique, we need to pay particular attention to, for example, whether a policy is motivated by the interests of the higher classes and comes at the cost of the right to exploit the interests of the lower classes. It is quite possible for policy makers to be influenced by the higher classes and to focus on the economic and political rights of those top groups, thus creating policies that favour the higher classes, making the higher classes more privileged, and the lower classes more exploited. A class-critical attitude towards society is therefore necessary to promote justice and the interests of the disadvantaged groups and lower classes.

Application

Introduction

Migration is a common and worldwide phenomenon, and it is interesting to see how class plays a role in this progress. I will first begin with a brief historical background of migration to help understand the formation of modern migration trends and flow. We will be able to see the different relationships and positions of classes at different periods. Following this, I will analyse the role of class in migration from the perspective of immigrants and countries by using class critique. The analysis mainly focuses on questions, for instance, who can migrate, which institution or power decides this, and who can get benefits?

Historical Background

Populations have been migrating since ancient times – to more fertile lands, to richer places or to completely new and vast territories. In the modern perspective of migration, the reasons that make people want to break up a settlement may be conflict or persecution, war, the search for better living conditions, study or work, and so on. These people who change their country of residence are defined by the United Nations as international migrants (United Nations, 2023). Data show that international migrants have accounted for an increasing percentage of the global population since the last century. Qiu (2005) divides the process of modern international migration beginning with the mass movement and migration of populations into four stages from a historical perspective.

The first was by the end of the 15th century and early 16th century, when Spanish colonists conquered a large part of the American continent and this was the beginning of the colonial stage. Then came the 1800-1914 period of industrialisation in Europe and the United States, the earliest into the industrialisation of the climax of the United Kingdom began to the Americas to the new continent of large-scale immigration, in addition, there was a wave of German immigrants. The mass emigration during the period of European industrialisation was due to economic development, not lack of development. It was also during this period that black slavery was gradually replaced by indentured labourers from Asia who were sent to the European colonies.

The outbreak of the World Wars contributed to the formation of the third phase. Between 1914 and 1960, the war interrupted the European boom in outward migration and most countries tightened their immigration policies. There was a decline in economic migration and an unprecedented increase in political migration, such as that brought about by prisoners of war, labourers, and territorial changes as a result of the war.

The last and current phase is the post-industrial period. In recent decades, the global exporters of migrants have shifted from Europe to the developing countries of the Third World. There has been a significant increase in outward migration from Asia, Latin America and Africa, and a decreasing proportion of outward migration from European countries followed by receiving large numbers of immigrants. Throughout this process, North America has been the oldest recipient of immigrants and still receives large numbers of immigrants. Europe, from being initially a major exporter of migrants, has become a major importer of migrants around the 1970s.

Our main focus here is on recent international migration, that is, post-industrial migration represented by international migration from developing countries to developed countries such as those in Europe and North America.

Migrants

There are various channels for international migration such as ordinary labour contracts, talent acquisition, studies, and marriage. These channels correspond to immigration measures that correspond to different types of potential migrants. For example, migrants can be categorised according to the amount of capital and the level of skills. They can thus be categorised as people with substantial resources versus people with very limited resources, low-skilled versus high-skilled workers, and so on. However, it is worth mentioning that these highly educated or high-skilled individuals are often referred to as “expatriates” rather than “immigrants” (Bonjour & Chauvin, 2018). They are certainly included in the category of immigrants, but the designation distinguishes them from other immigrants.

People may want to go to richer countries, pursue higher wages, get a better education for their children, and escape from chaos and strife, so they may then become potential migrants. Of these people who want to migrate, not all are able to complete international migration. Van Hear (2014) received this response in an interview, “I will go as far as my money can take me”. In other words, migrants make choices of channels and destinations that are not determined by their will, but by the capital they have or the resources they can gather. The desire to achieve international migration usually requires the accumulation of large amounts of capital in various forms. Only those with resources or privileges can choose the channels and destinations they want to migrate to, or at least a destination they can afford, while those with insufficient resources have to stay in their original regions. Ownership of resources, privileges and capital usually depends on class. Class can therefore be seen as a major determinant of migration.

Upon realising international migration, in addition to potentially having higher wages or a better quality of life, people may also experience class mobility. Immigrants’ sense of their position in the class hierarchy may experience both upward and downward mobility (Bonjour & Chauvin, 2018). Compared to their home country, they have a better life, but at the same time, they are highly likely to experience downward mobility of class as the capital used to migrate is depleted and as they seek to reintegrate into a new society. This may be reflected in relatively less capital, a downgrade in consumption, a fresh start in social status, etc.

Here we call the countries that export migrants and the countries that migrants leave as home countries. Other names have been used, such as sending country, exporting country, host country and so on (Van Hear, 2014). The countries that receive the migrants are the destinations of the migrants and hence have been called destination countries, other scholars also call them receiving countries (Bonjour & Chauvin, 2018).

Impact on Destination Countries

Destination countries consider migration from two perspectives, market demand and social control, and there are tensions and possible contradictions between the two sectors (Marfleet, 2022). The consideration of market demand is centred on economic issues, focusing on the costs and benefits of migration for the home country. The consideration of social control focuses on culture, identity, power and policy. According to Engels, class conflict intensifies, and state institutions intervene directly to ensure that the bourgeoisie consolidates its hegemonic position (Marfleet, 2022). Considering the class mobility of immigrants mentioned earlier, this intervention is a challenge for newly arrived immigrants, especially those who do not have a lot of capital to ensure that they remain in the upper class in the new society.

The classic view of class critique should argue that immigration serves the market, driven by economic considerations in the pursuit of profit. When considering their attitudes towards immigration and formulating their immigration policies, the destination countries’ consideration of potential immigrants is not based on the applicants’ individual characteristics and strengths, but only on how they will benefit themselves. If the immigrant belongs to an upper class, a promising class, then he/she is likely to be perceived as beneficial to the destination country. These groups that are more likely to have access to opportunities have “economic entitlements” that represent class, culture and stereotypes. The collective entitlement of the upper classes is likely to imply the collective undesirability of the other classes, which may be corresponding to an exploitation of the weaker classes.

Many scholars have argued that the labour provided by immigrants is the main reason for destination countries to accept incoming immigrants (Bonjour & Chauvin, 2018; Marfleet, 2022; Van Hear, 2014). Low-skilled workers imply a large pool of cheap labour that is attractive to some employers in destination countries. If certain specific skills are in demand in the local labour market, low-skilled workers could benefit from the corresponding immigration policies. High-skilled groups are generally perceived to integrate well and, importantly, to produce more profit. Immigration policy is thus a top-down process of selecting potential immigrants to meet economic concerns.

Impact on Home Countries

The impact of international migration on home countries is mainly a brain drain. Due to the high costs usually associated with international migration, as mentioned in the previous section, it is often difficult for people in the lower classes to afford them, and therefore they are unable to migrate internationally or to migrate through official legal channels. In contrast to the situation in the destination countries, where migration can solve the labour shortage problem to some extent, a study on international teacher migration showed that international recruitment does not lead to labour shortage in the home countries but leads to brain drain (Appleton et al., 2006). The labour in the outflow is usually more effective than the local labour force and therefore represents a loss to the local market and government. However, Appleton et al. (2006) also found that the local labour force tends to perceive labour outflows as beneficial to them because it creates more jobs. A mass exodus of quality labour may imply a reshuffling of the local labour market and may also lead to many opportunities for class leapfrogging. Thus for the local market, international migration means a decrease in work efficiency, but for the local labour force, it means that they will have more opportunities to move to a higher class.

Conclusion

Class often plays a decisive role in the process of migration and influences migration policies, trends and outcomes from the perspective of destination countries, home countries and individuals. However, we do not often see “class” directly in documents or official policies, but rather as capital requirements and criteria that set the bar for potential migrants. Immigration policies cater to the needs and interests of the importing countries, and through these policies, the importing countries select those who meet the criteria, especially those potential immigrants who can generate profits for them. Migrants who meet the criteria and have enough capital in various forms come to the new society in search of a better life, and they may have to face upward and downward class mobility. Throughout this process, lower-class potential immigrants are excluded from international migration policies; they neither have enough capital, nor do they have the skills that would bring profit to the importing country if there was no match with the market demand in the importing country (for example, a case of matching is the market demand for cheap labour). These people who are not considered part of the promising class are exploited in their quest for a better life and find it difficult to make the class leap or find opportunities to emigrate due to class and stereotype entrenchment. As a result, while those in the middle and upper classes realise international migration, the rest are left to stay put or migrate illegally. In this way, immigration, or official international migration, from a class-critical point of view, is entirely a means to benefit the ruling and upper classes combined with the exclusion of the needs of the lower classes.

Philosophical Exercises

- Imagine yourself in a higher class. How would your political, economic and life needs be different? Would the fulfilment of these needs mean the exploitation of other classes?

- Try to apply class critique to daily life rather than always to philosophical or political thinking, e.g., in a relationship or interaction with another person. Try to observe if a person in a higher position is more likely to rely on his/her own interests to dominate this relationship or interaction.

References

Appleton, S., Morgan, W. J., & Sives, A. (2006). Should teachers stay at home? The impact of international teacher mobility. Journal of International Development: The Journal of the Development Studies Association, 18(6), 771-786.

Bonjour, S., & Chauvin, S. (2018). Social class, migration policy and migrant strategies: An introduction. International Migration, 56(4), 5-18.

Lawford-Smith, H. (2016). Offsetting class privilege. Journal of Practical Ethics, 4(1).

Marfleet, P. (2022). Marxism, Migration, and the State. In Marxism and Migration (pp. 57-81). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Qiu, L. (2005). International Migration: Its History, Present Situation and China’s Related Policy. Overseas Chinese History Studies, 3(1), 1-16.

United Nations. (2023). International migration. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/migration

Van Hear, N. (2014). Reconsidering migration and class. International Migration Review, 48, S100-S121.