13 Ambiguity and Migration: Are We All Immigrants, After All?

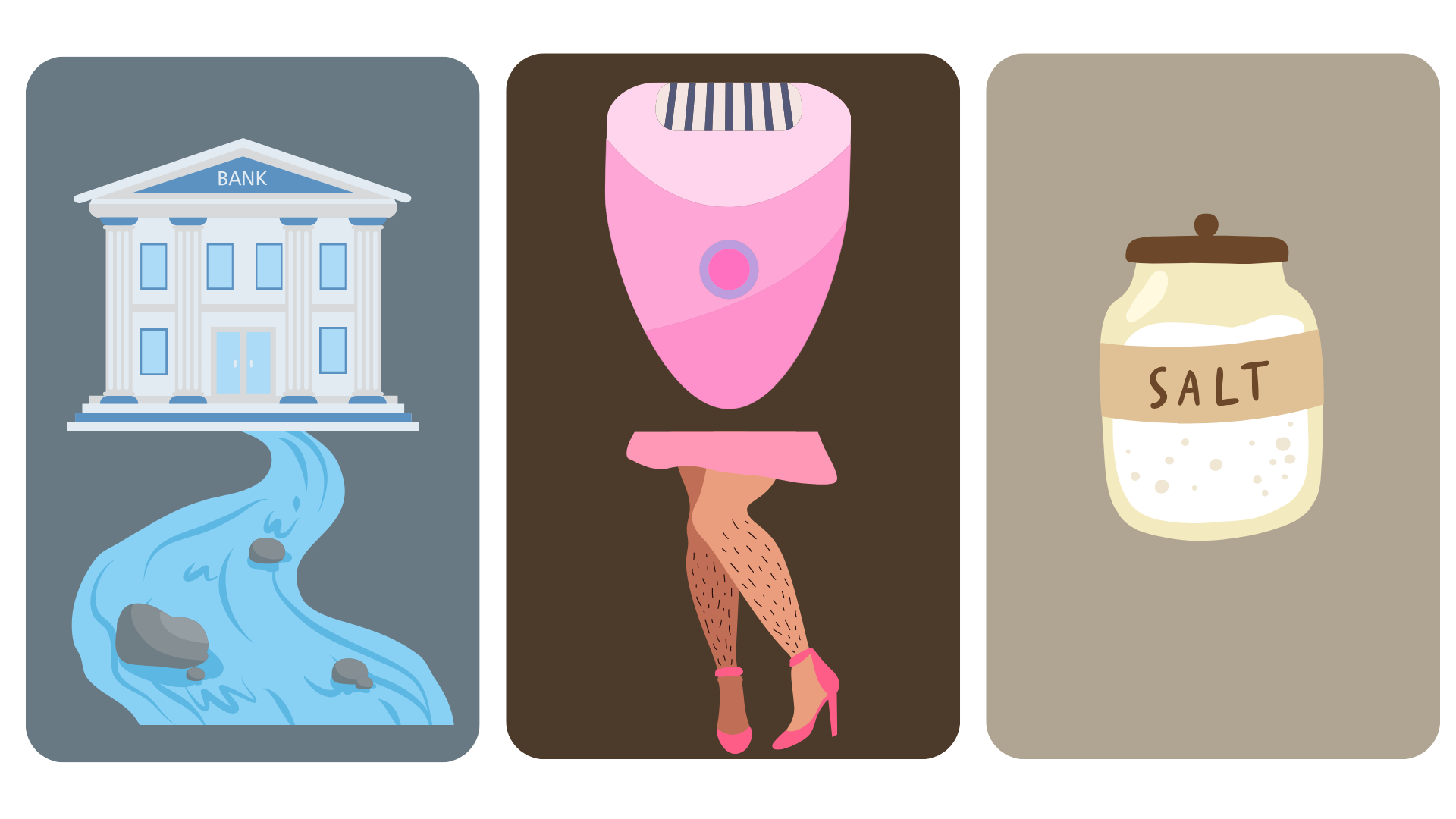

It is a cozy Saturday morning. You are just walking out of the house with the car key in your hands, when your mom asks: “Where are you going?” “I’m going to the bank!” you answer. “Wait!” She rushes down the stairs with your purse and starts laughing when she sees a big backpack on your shoulder with fishing rods sticking out of it.

AMBIGUITY occurs when something can be interpreted in more than one way which causes the audience to be confused. This, however, by no means suggests that we always want to avoid ambiguity. Rather, they can be unexpected surprises in songs, poets, movies…

In the “Nothing gold can stay” by Robert Frost, he writes “Nature’s first green is gold, Her hardest hue to hold.” Here, “gold” represents two layers of meaning. In a literal way, the color of leaves are usually gold before they turn green. On the other hand, “nature’s first green” is usually something very valuable, just like gold. The existence of ambiguity creates this beautiful imagery of new leaves. However, things can be very different when ambiguity is used in a philosophical context. Specifically, it is different from several terms that share similar meaning in casual use.

In the “Nothing gold can stay” by Robert Frost, he writes “Nature’s first green is gold, Her hardest hue to hold.” Here, “gold” represents two layers of meaning. In a literal way, the color of leaves are usually gold before they turn green. On the other hand, “nature’s first green” is usually something very valuable, just like gold. The existence of ambiguity creates this beautiful imagery of new leaves. However, things can be very different when ambiguity is used in a philosophical context. Specifically, it is different from several terms that share similar meaning in casual use.

Different Kinds of Ambiguity

Just as any kinds of philosophical terms, ambiguity in philosophy takes various forms.

Lexical or Linguistic

Lexical or linguistic ambiguities are the most common ones where one single word has more than one meaning. The “bank” example above is a demonstration of such ambiguity. Identifying this type of ambiguity is relatively straightforward. You just need to observe and determine the different meanings of the word that are reasonable within the sentence. A famous philosophical ambiguity of this kind is the Frege-Russell “is” ambiguity, which argues that “is” can have two different meanings: “be equivalent with” or present a relationship of belonging. For instance, when we say “water is H2O”, we mean that the term “water” is equivalent to the chemical formula H2O. On the other hand, when we say “water is liquid”, we are introducing water as a type of liquid, as the category of liquid includes a larger variety of elements and components than just water.

Synthetic

However, sometimes, ambiguity occurs within sentences rather than single words, where the structure of the sentence itself leads to multiple interpretations. For example, the phrase “superfluous hair remover” can be understood as both “a remover that removes superfluous hair” and “a superfluous remover that removes hair”. The interpretation depends on whether one perceives “superfluous” as describing the “remover” or “hair”. Therefore, it is not any of the three words making this quote ambiguous, but rather the structure of the quote. It is worth noticing that although Groucho Marx’s quote seems to belong to ambiguity of this type, it is in fact the meaning of “in” makes this quote ambiguous. (i.e. whether “in” means wearing something or within something) Thus, it belongs to the previous type.

Pragmatic

How about the ones that don’t fit precisely into either of these categories? For instance, when someone asks “Can I have the salt?”, they are typically requesting you to pass the salt to them. However, if we take the literal meaning of the sentence, it will sound like the person is asking if he is able to have the salt. These kinds of ambiguity involve what’s known as pragmatic ambiguity, when the literal meaning of a sentence differs from its typical interpretation in specific social and communicational contexts.

In conclusion, though language is limited, the complexity of the world often adds layers of meaning to a word or phrase based on the context. Even the word ambiguity itself, as demonstrated above, can be interpreted differently depending on whether it is used in a philosophical context. To clarify, ambiguity can be as straightforward as rephrasing a sentence, or just directly conveying your idea such as showing your mom you are going to fish rather than going to the financial institution. But in other cases, it may require systematic and extensive effort. For instance, in Simone de Beauvoir’s book The Ethics of Ambiguity, she points out that ethical judgements are never simple black-and-white judgements. They often carry a sense of ambiguity and need to be considered within the context of individual circumstances.

In conclusion, though language is limited, the complexity of the world often adds layers of meaning to a word or phrase based on the context. Even the word ambiguity itself, as demonstrated above, can be interpreted differently depending on whether it is used in a philosophical context. To clarify, ambiguity can be as straightforward as rephrasing a sentence, or just directly conveying your idea such as showing your mom you are going to fish rather than going to the financial institution. But in other cases, it may require systematic and extensive effort. For instance, in Simone de Beauvoir’s book The Ethics of Ambiguity, she points out that ethical judgements are never simple black-and-white judgements. They often carry a sense of ambiguity and need to be considered within the context of individual circumstances.

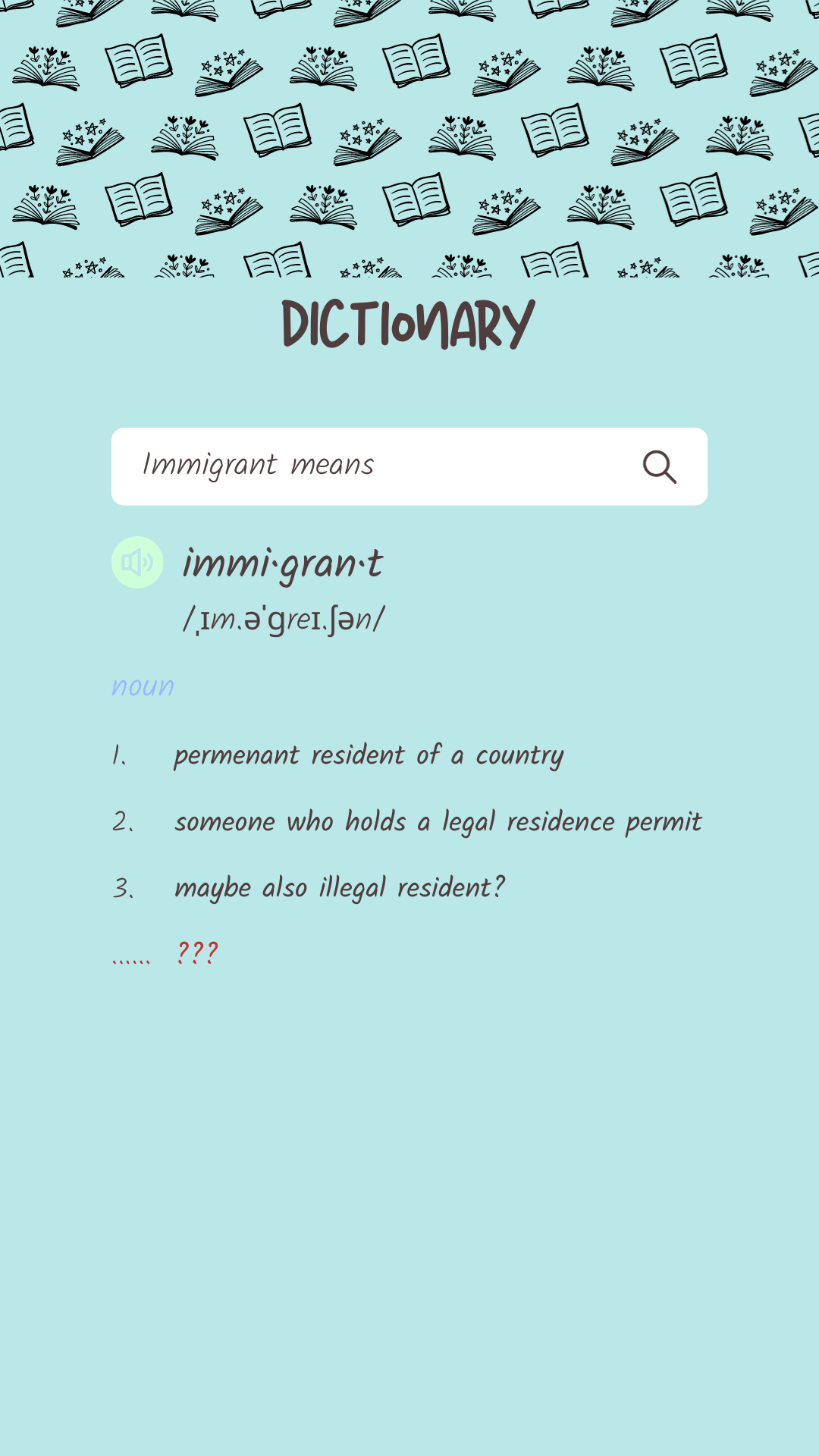

Lexical Ambiguity

The most prominent source of ambiguity concerning immigration relates to the usage of the term “immigrant.” Typically, when someone states, “I am an immigrant (of a country),” they are indicating that they have acquired the legal documentation to become a permanent resident of that country. It is unlikely for individuals who are just traveling, studying, or working in the country temporarily to label themselves as immigrants. On the other hand, those who have obtained citizenship may identify themselves by the nationality of the country, saying, for instance, “I am Dutch.”

The most prominent source of ambiguity concerning immigration relates to the usage of the term “immigrant.” Typically, when someone states, “I am an immigrant (of a country),” they are indicating that they have acquired the legal documentation to become a permanent resident of that country. It is unlikely for individuals who are just traveling, studying, or working in the country temporarily to label themselves as immigrants. On the other hand, those who have obtained citizenship may identify themselves by the nationality of the country, saying, for instance, “I am Dutch.”

However, this definition also depends on the context. For example, when we consider the term “immigrant” within a legal context, the story is completely different. According to the Immigration and Naturalization Service, individuals can hold various immigration statuses, such as living as a family member or partner of a citizen, for work, for study, as an au pair, as a long-term EU resident, or as an asylum seeker within the country etc. For instance, the phrase “student immigrant” is used to describe students who are residing in a country other than their home nation for a period exceeding 12 months. They are also required to apply for a residency card and register with the municipality. Moreover, we employ “immigrant” to refer to individuals who have acquired the nationality of the host country, even including their children who were born and raised in that country (often referring to them as “second-generation immigrants”) when comparing them to people with multiple generations of ancestors residing in the country. Thus, depending on the context, the scope of the term “immigrant” can be significantly broader than its common usage.

This Ambiguity Is Problematic Because…

“Why would it be problematic?” you might wonder. People can tell the difference when it is used in different contexts, right? However, even the “common use” is not agreed among people who are labeled as immigrants and who are not. In fact, researches have found that whether someone is perceived as an immigrant could be irrelevant of whether they have an immigration experience (Bengtsson et al., 2011). For example, people with a more “foreign look”, which is an appearance (skin, hair, eye color, facial structure, etc.) that is different from the majority of the population within the country, are more likely to be perceived as an immigrants, even if they speak perfectly fluent official language or act in the same manners as the “natives”. The natives or the dominant population has the initiative power of labelling who the immigrants are; which creates an imbalance of the conception of immigrants not only between the natives and the immigrants, but also among the immigrant groups according to their original ethnicity.

This “ambiguous” self-identification extends to immigrants themselves through instances when they realise that fitting into the expectation of one identity conflicts with the expectation of another. For instance, the debate between marrying a person that represents the tradition of their original nationality and one that represents the country they are currently staying in never stops (Karthick Ramakrishnan, 2004).

Moreover, the distinction doesn’t become clearer even if we refer to legal definitions and relative immigration policies. In fact, the ambiguity could become a tool for more political support (Schultz, 2020). Since the ambiguity creates more leeways for the local officers to execute the policies in favor of local situations, being ambiguous avoid generalising the policies. However, the Schultz paper also points out that local officials in Germany face similar difficulties as the central government. It is hard for them to examine all the information of each immigrant regarding all the manners they are dealing with. Thus, they were also using the “common use” as a resource of their decisions. This suggests that decisions are correlated with the original nationality of the immigrant, which reflects the criticism above.

Thus, the following questions posed by Bengtsson are worth our deliberation. Are we just resembling the ethnic hierarchy that already exists in the country again in the immigrant community? More fundamentally, who are immigrants? They mentioned a conversation between a professor and a female immigrant in the book where the immigrant has been living in the country for many years and wants to dispense of the label of “an immigrant”. The professor, however, affirmed her that she is still an immigrant and will be one as long as she has the experience of immigration with her. Therefore, the problem rises when the ideal self-identification of an immigrant may be incongruent with the common social perception he or she receives.

Speech Acts and More Prominent Problems

While the previous section has discussed how a lexical ambiguity of the word “immigrant” can cause hidden problems, this section will demonstrate how the use of “immigrant” can become a speech act and cause actual harms.

As Spanish is the second most spoken language in the U.S., the Spanish or the Hispanic population no longer seems to be a minority population in the country. You might think that the label “Hispanic” probably makes the population closer to the mainstream American culture. However, studies have shown that this label actually causes negative consequences. Alejandro Portes and Dag MacLeod, in their study surveying children of immigrants in southern Florida and southern California, found that the children who identify themselves as Hispanic are more likely to have poorer English skills, lower self-esteem and higher rates of poverty (Portes & MacLeod, 1996). Harms like these are caused, at least partially, by the label of “immigrant” and thus the self-identification of being an immigrant. Therefore, labelling and stigmatising caused by ambiguity leads to more than confusion.

The source of this harm is the underlying assumption of excluding the person from the dominant social group. “Immigrant” indicates that someone’s “root” or ancestors aren’t from the country. There are many underlying assumptions coming with this intuition. Therefore, by calling the person an “immigrant”, it becomes an act of excluding them: for example, new immigrants who identify themselves as a citizen of the country and are sensitive to their identities. They may agree with the values that the country promotes (e.g. a new U.S. immigrant agreeing with democracy and protecting human rights), they speak the language, they try to blend into the community and make meaningful connections with the locals. Furthermore, these exclusions come with realistic social consequences, such as lower socioeconomic status and racism.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the concerns stated above stem from the fact that the word “immigrant” comes with assumptions that are generalized without careful deliberation. Even within the population of immigrants who decide to join the nationality, there is more than one kind of lifestyle regarding their connections to their previous country. For instance, one can maintain a close relationship and agree with the values of the country one comes from not blending into the new country; one can also do the opposite. Most realistically, people will keep connections with both their mother nation and their new nation.

Are we all immigrants after, all? In some sense, we can all be characterized as 10th generation, 50th generation immigrants and this tracing back won’t end before the beginning of the human era. So the question left to be considered is, what kind of perspectives should we take regarding whether to view others or ourselves as immigrants. More importantly, how can we act accordingly?

References

Bengtsson, B., Strömblad, P. and Bay, A.-H. (2011) Diversity, inclusion and citizenship in Scandinavia. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars.

Karthick Ramakrishnan, S. (2004) ‘Second‐generation immigrants? the “2.5 generation” in the United States*’, Social Science Quarterly, 85(2), pp. 380–399. doi:10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.08502013.x.

Portes, A. and MacLeod, D. (1996) ‘What shall I call myself? Hispanic identity formation in the second generation’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 19(3), pp. 523–547. doi:10.1080/01419870.1996.9993923.

Schultz, C. (2020) ‘Ambiguous goals, uneven implementation – how immigration offices shape internal immigration control in Germany’, Comparative Migration Studies, 8(1). doi:10.1186/s40878-019-0164-0.