3 Foucault’s Discourse Analysis

Giuseppe Carretta; Stijn Hospers; and Will Shengbo

Description

Short Introduction of Foucault and the Different Methods We’ll Discuss

Michel Foucault (1926-1984), that titan of France, grew great as he did in that plethora of fields not through a single-minded occupation with theoretical philosophy, but through the development of a distinctive blend of history and philosophy. Spanning topics as diverse as sexuality in ancient times to the emergence of the modern penal system, his oeuvre is hard to characterize without referring to Foucault’s philosophical preoccupations. On the other hand, Foucault has left very little in terms of hard theoretical writing, given that most of his major works are histories – and rather formal, academic histories – of some kind. Somewhere in the later years of his life, Foucault started insisting that all of his major works could be read as “parts of a single project of historically investigating the production of truth”.[1] Perhaps this is indeed the best way to communicate the coherence of his work.

Foucault’s research can be divided into work done according to two ‘methods’, which employ a single, broad, interpretive technique. These two methods are “archaeology”, associated with the first part of his career, and “genealogy”, associated with the later part. Both these methods generally involve the unearthing of meaning in bygone times through an analysis of discourse which is to say “discourse analysis”, the earlier mentioned overarching technique in Foucault’s work. This entry will be structured according to the above division of Foucault’s work, presenting the gists of “archaeology”, “genealogy” and “discourse analysis” seriatim.

Archaeology

The method of archaeology is focused on the archaeology of knowledge. The metaphor of archaeology can be best understood as knowledge that lies beneath the surface and which can be excavated. But there is a difference between the history of knowledge and the archaeology of knowledge. The conception that Foucault’s method is simply ‘dusting off’ ideas through reading history is skewed (incomplete?). Whereas history operates only on the level of concepts and theories of particular sciences, archaeology operates at the level of the cognitive structures that define the shared cognitive field in which these concepts and theories are deployed (Lawlor & Nale, 2014). The method of archaeology does include reading historical texts in a certain domain at a certain time, but the focus is on the ‘determining fundamental rules governing the use of language in that written corpus’ (Lawlor & Nale, 2014). To put it in simpler terms; with this method we are not merely interested in the concepts from a different period in time, but also in how this discourse in that period is limited or governed.

Foucault would not deny that humans influence the making of their history. But he would claim that this role is limited by the ‘discursive formation’; a complex of rules that define the sorts of objects, concepts, forms of cognitive authority (“enunciative modalities”), and theoretical viewpoints (“strategies”) that are possible in a given historical context (Lawlor & Nale, 2014). Different periods in time therefore have different discursive limitations. For instance, in the book Madness and Civilization, Foucault examines the concept of mental illness in Europe. The treatment of mental illnesses (or madness) was seen in the modern time (19th century) as an enlightened liberation of the mad from the ignorance and brutality of preceding ages (Gutting, 2022). But, as Foucault wanted to point out, this conception of the mad as being sick and in need of treatment was not a clear improvement from earlier conceptions. For instance, in the Renaissance period, the mad were depicted in art as having a certain wisdom and there was a generally accepted idea that the mad were in contact with mysterious forces of cosmic tragedy (Gutting, 2022). What was presented in the modern times as an unquestionable scientific discovery, was more the product of questionable social structures.

The archaeological method, though only theoretically enunciated in 1969 in The Archaeology of Knowledge, characterized the earlier of Foucault’s works. In Madness and Civilization (1961), but too in The Birth of the Clinic (1963) and The Order of Things (1966), pertaining to the history of the modern medical science and the history of the so-called ‘human sciences’ (biology, political economics, linguistics), respectively, Foucault probes for the linguistically-rooted epistemic conditions of ages past, the confines of knowledge, with a special eye for the hidden logic of their changing. In the early ‘70s though, as he grows more active politically, Foucault advances a similarly-minded, but subtly different method of doing history: “genealogy”.

Genealogy

When we encounter the concepts of “power” and “knowledge” at the same time, it may be difficult to find a connection between the two. Typically, we think of power in terms of politics, while knowledge is the pursuit of truth. But whose truth is it? Where does the authority of truth come from? With the help of Foucault’s genealogy, we might have some unique discoveries.

“Genealogy (thus) means origin or birth, but also difference or distance in the origin.”[2] Like Foucault’s archaeological approach to knowledge, genealogy as a philosophical method also has meanings that differ from what itself refers to. Originally, it was a method for locating and classifying the origins of noble families. For Nietzsche, it was used to examine the derivative relationships of morality. Foucault’s genealogical analytical method is also developed from the latter – in many arguments, Nietzsche’s book On the Genealogy of Morality played a role as his important reference. Nietzsche delved into the past of morality that stretches infinitely into darkness, or rather, the history of values and meanings. While it may seem like a work of tracing origins, this kind of genealogy emphasizes the heterogeneity, contingency and rupture of historical facts, aiming to oppose the metaphysical pursuit of the continuity and essentialism of origins. “Genealogy does not oppose itself to history as the lofty and profound gaze of the philosopher might compare to the molelike perspective of the scholar; on the contrary, it rejects the metahistorical deployment of ideal significations and indefinite teleologies. It opposes itself to the search for ‘origins’.”[3] There is opposition, struggle, and overturning between different systems of moral evaluation. “Genealogy means both the value of origin and the origin of values.”[4] The crystallization derived from Nietzsche’s genealogical method does not show that value is a linear progress. Behind its true history lies the naked history of power— the struggle between masters and slaves over moral discourse. Foucault’s genealogy also presents itself as anti-essentialist historicism. The continuation of knowledge and discourse is not a linear development but the result of struggle.

As mentioned before, if we liken Foucault’s archaeology to digging for knowledge beneath the surface, ‘reading historical texts in a certain domain at a certain time,’ then this can be seen as a horizontal, synchronic analysis done after selecting a specific geological layer. Its limitation lies in the lack of diachrony, making it unsuitable for studying the effects of specific events or activities. Genealogy, on the other hand, is a vertical, tree-like structure, a supplement and continuation of his earlier knowledge of archaeology. Archaeology is more concerned with how discourse or knowledge is expressed, but why some are called “knowledge” or “truth” while others become “opinions” directly relates to the operation of power by the speaker, this is where genealogy comes on stage.

In summary, as a standpoint, Foucault’s genealogy follows Nietzsche’s direction, opposing the essential development of history, emphasizing the irreconcilable contradictions, and questioning truth as merely the result of struggles between discourses. “If the genealogist refuses to extend his faith in metaphysics, if he listens to history, he find that there is ‘something altogether different’ behind things: not a timeless and essential secret, but the secret that they have no essence or that their essence was fabricated in a piecemeal fashion from alien forms.”[5] As a method, it is not aimed at restoring fractured history, but rather, in these fractured facts, it explores the mechanisms of how ‘knowledge-power’ is mutually constructed, and how individual and individual discourses are produced under the operation of this construct. “A genealogy of values, morality, asceticism, and knowledge will never confuse itself with a quest for their ‘origins’, will never neglect as inaccessible the vicissitudes of history, On the contrary, it will cultivate the details and accidents that accompany every beginning; it will be scrupulously attentive to their petty malice; it will await their emergence, once unmasked, as the face of the other.’”[6]

Discourse Analysis and the Overlap of Foucault’s Methods

The ‘methods’ of both archaeology and genealogy share one enormously central preoccupation: a preoccupation with discourse. In either method, discourse is shoved forward to become the central vehicle of analysis and sense-making. Foucault’s work in explicating discourse theoretically, and especially in its relation to power and knowledge, and revealing discourse analysis practically, has been, and is, central in the development of the social sciences.

“”Discourse” in this sense is usually a mass noun. Discourse analysts typically speak of discourse rather than discourses, the way we speak of other things for which we often use mass nouns, such as music…”[7] A mass noun means a unified body of matter with no specific shape; and one can begin to find some parallels with the notion of “migrants” and “migration”. What are the origins of the word “Migrant”? What are its connotations? Has the meaning of “Migrant” remained the same throughout the years?

The object of discourse analysis is to study language use that goes beyond the sentence boundary. Yet it also prefers to analyze “naturally occurring” language use. By language beyond the sentence, we intend to say the studying of larger chunks of language as they flow together. Thus “frame analysis” is important. This is a type of discourse analysis which seeks to ask what activity the speakers are engaged in when they speak on any given subject or topic. What do they think about when they are talking this particular way and in this particular time? Thus, frame analysis implies history (or archaeology in terms of Foucault), it implies historical context and a form of relationship between the past and the present (or genealogy in terms of Foucault): “History should not be used to make ourselves comfortable but rather to disturb the taken-for-granted.”[8] While frame analysis will not be the focus of our discussion, its core theme and aspect will be central to tackling the discussion of migration. This is due to the fact that frame analysis looks to the foundations of how people develop ideas and activities. Any idea, stereotype and concept must have had a basis in history, an origin, so to speak. Moving on from this, we need to answer the most important question: what is discourse analysis? What does it argue for?

In a broad sense, it is the study of language and its effects. This overlap in different areas is quite evident in Foucault’s methods. When it would come to analyzing any one thing, language, in our case, there needs to be reference to the past. This will be our foundation: “Foucaultians are not seeking to find out how the present has emerged from the past. Rather, the point is to use history as a way of diagnosing the present.”[9]

Application

Stijn

In this application, I will make use of Foucault’s methodology on the subject of ‘migration’. As is described in the general method section in this book, Foucault used historical texts on topics like punishment, medical perception and insanity. His reading of these texts and his archival work was extensive. Not only could he investigate the discourses in specific societies deeply, he could also note the differences (in discourse) over a long period of time. This application, because of its size, shall be more modest. Therefore, I will mainly focus on migration in the early modern period (1550-1800) in the Netherlands. This period is marked by great diasporas and housing big numbers of migrants on which I will explain hereafter. I cannot account for all migration flows occurring during that time, but the main migration events with the biggest impact will be discussed. Not only are these statistical facts of movements of people interesting and important, but to stay true to Foucault’s methodology I will focus on the discourses of migration in the early modern period in the Netherlands. Despite this application being modest in size, I hope it can still shed light on some of the differences in discourse on migration between the early modern period and today.

First, I will give insight on the discourses within the early modern period in the Netherlands, its impact on the overall culture and the attitude towards migrants and the term ‘migration’ by making use of G.H. Janssen’s essay ‘The Republic of the Refugees’ (2016). I then move to some comparisons between discourses in that period and the discourses of today and try to show in which way it is limited (or not). I will conclude by bringing these facets together.

Discourse on Migration in the Early Modern Period

In general, communities that get confronted with big numbers of ‘strangers’ in their country do not generally react with pure positive attitudes. This was no different in this period in the Netherlands. But despite this, a gradual shift in the discourse and attitude towards ‘migration’ occurred that made it more a common virtue.

Since most of the Netherlanders were protestant, its influences reached into daily life and this translated into the general perspectives. Biblical parallels were used to reinforce a more heroic reading of migration; ‘by comparing contemporary refugees to ‘Israel’s children’, Reformed ministers linked the confusing experiences of displaced Netherlanders to venerable stories of the biblical tradition.’ (2). The diaspora of returned exiles (slight ahead in time of southern immigrants) was broadly imagined as an honourable spiritual experience.

One of the big population movements happened during the Eighty Years War (1568-1648). Around 100,000 people moved from the southern part (what is now Belgium) to the northern part in a short period of time due to an attack on religious freedom, rising taxation and a threat to local autonomy. This population (mainly families) was around 7 percent of the total population of the Netherlands (then ‘the Republic’) in that period of time (1).

Although these southern immigrants greatly benefited the Dutch economy, there were also three recurring themes of critique around the theme of migration that Janssen points out. One, the local elites wanted to keep these southerners out of office. In an essay written during that period, the mayor of Amsterdam was quoted in saying that ‘the management of affairs’ should be in the hands of ‘persons of a prudent, steady, and peaceable disposition, which qualities, I believe, prevail more among the natives than among those who have come here to live from other lands’. Second, religious differences between Calvinists and Reformed Protestants added to this political exclusion. And third, critics of migration were afraid of a certain moral degeneration because of the extravagant behaviour of some wealthy refugees.

Shifting tides in the ongoing war resulted (at around 1600) in a (re-)invention of the Dutch identity through rising patriotism. Historic readings from the Batavians fighting against the Romans became the breeding ground for an identity focused on ‘freedom’. The link was made with the war happening at that time that envisioned the Dutch people as freedom seekers where religion, whatever preference, was accepted. However, interesting to note, this imagery was for a great deal created by immigrants. Batavian stories and biblical parallels (Israel’s children) shaped the vocabulary about freedom (of religion) as something typically Dutch and migration therefore developed into a more broadly defined code of social respectability (2).

Discourses on migration during the seventeenth century were mixed, but tilting towards a more positive view. These new immigrants were accused of putting pressure on housing markets, charitable facilities and discourses of exclusion were commonplace but they were also ‘highly permeable and fragmentary’ (2). Not only was the religious aspect of immigrants important for the image of the Netherlands, the economic part of the equation became more apparent and this in turn helped the gradual shift towards a view that being a refugee in the Netherlands was not problematic; it became a respectable category in Dutch society (2).

New generations of immigrants, in line with those from the South, influenced more inclusive local and national discourses. The reconceptualization of Amsterdam as a tolerant cosmopolitan city was for a large part due to creators of texts and images that came from migrant families. Groups of migrants and religious diversity are explicitly mentioned by these second generation writers (s.a. Olfert Dapper and Caspar Commelin) and are portrayed as typical of Amsterdam and a source of local pride (2).

Changes in Discourse

While writing the piece above I noticed striking similarities between the discourse then and now. The question whether immigrants will endanger the national identity seems timeless (3). As Janssen points out, this rise of nationalism or patriotism is reoccurring with every wave of new immigrants. Practical accusations such as immigrants who are pressuring the housing market and discourses of exclusion are just as commonplace as they were then.

I however want to focus on the differences. It seems that there are three important factors that were able to change the negative discourse of migration into a more positive and tolerant discourse. These are economic influences, the influence of the church/biblical readings and the influence of the migrants themselves.

Of the three, the economic influence seems the most common to the discourse on migration today. Besides the cultural aspect, which after Pim Fortuijn and 9/11 have taken over most of the discourse on migration in the Netherlands, does the economic influence play a large part in the discussion of how many refugees are welcome today. Not only was the economic opportunity a reason of migrants to come to the Netherlands in the early modern period, the cost-benefit analysis of migrants also played a role in the discourse of migration. This shifted towards a narrative that highlighted the economic advantages of refugees. Migration did eventually play a large part in building the Netherlands as we know it today by working in the fields, setting up shop in big cities or helping with the VOC.

The biblical and religious influences on the discourse in the early modern period are undeniable. It is safe to say that in the early modern period, religious repression was the main reason for people to leave or flee their country besides economic incentives. Although religious refugees are as common now as they were then, it seems that the discourse is not so much, or at least much less, influenced by religious sentiments here in the Netherlands. I am not talking about the cultural differences resulting from religion, since that has become the major component of today’s discourse (think here of the discussion whether Islamic immigrants clash in Dutch society, although counter to this, one could think of all the different religions of the refugees that have come to the Netherlands in the early modern period (Huguenots, Jews etc.)). But the main difference is that biblical parallels are not as present when we talk about migration. It is not an illogical claim to say that secularization has influenced discourses on migration. How effective would a heroic reading of migration be today if it would link biblical stories to it? It is safe to say that the ‘Israel’s children’ example was more impactful in the early modern period than it would have been today.

What struck me the most surprising is the major influence of immigrants themselves in the discourse on migration. Immigrants intently tried to shape a vocabulary that was on the one hand patriotic and on the other hand inclusive. Although this lead to friction with the establishment early on, it eventually resulted in a discourse that was seen as typically Dutch. The full explanation to how this was possible is difficult to trace, but one of the reasons was a flexibility in language. The range and meaning of the terms ‘refugee’, ‘exile’, and ‘diaspora’ may often have been blurred in seventeenth-century Dutch texts, but as Müller’s Exile Memories explains, it was exactly this flexibility that allowed new groups of migrants to appropriate part of this vocabulary (2). The influence of immigrants in discourse (Olfert Dapper etc.) also shows that some immigrants had the opportunity to get involved with public discourse and eventually, over a period of time, held influential positions in society.

To draw a narrative Foucauldian thread through all of this would be to find an answer to the question of how the discourse on migration in this period was limited or governed. Three factors that seem to be the most reasonable answer to this are the fact that most of the establishment (and society in general) at that time was religious, that individuals had a certain freedom to voice their opinions whatever background they had and that individuals were able to climb the social ladder. As already mentioned, religion was a big factor in the reading of migration and these biblical readings were spread by reformed ministers. But also the influence of the church on political institutions, let alone ordinary citizens, was very great at that time. The church and the political institutions would have governed, or at least guided towards, these biblical readings. Besides, the fact that individuals had the opportunity to climb the social ladder in the Netherlands and that ordinary citizens were able to voice their opinion are two factors that demonstrate an open climate in society. It seems that if one was contributing to society that, whatever background, one was able to reach influential positions and even influence the major discourses on topics like migration.

To conclude, this application has taken a case study of the discourse on migration in the early modern period in the Netherlands. I have examined various factors of the shift in discourse from hostile to tolerant during this period. Although modest in size, this application is able to show some of the main discussions on migration and my Foucauldian methodology adds to the answer of how the Netherlands came to be known as ‘the Republic of refugees’.

References

- Lucassen. J. (1994). ‘The Netherlands, the Dutch, and Long-Distance Migration in the Late Sixteenth to Early Nineteenth Centuries’, in Nicholas Canny (ed.), Europeans on the Move: Studies on European Migration 1500–1800(Oxford, 1994; online edn, Oxford Academic, 3 Oct. 2011).

- Janssen, Geert. (2016). THE REPUBLIC OF THE REFUGEES: EARLY MODERN MIGRATIONS AND THE DUTCH EXPERIENCE. The Historical Journal. 60. 1-20.

Giuseppe Carretta

“History should not be used to make ourselves comfortable but rather to disturb the taken-for-granted.“[1]. With this application, I will discuss how the ideas and definitions behind “migration” have changed and involved over time. This will be done through the lens of Foucault’s discourse analysis. There are many different reasons as to why the changes to definitions, even not strictly tied to migration, may have and are, in fact, still occurring today. These reasons can vary significantly in relation to the period in time as well as place. The goal within this chapter is that of understanding the various forms of migration in relation to the very people undertaking these travels as well as the to the people who are not migrants and so witness the movement of people. There are many more reasons and forces to why a person may decide to migrate. Before we can begin with this application, a distinction between involuntary and voluntary migration needs to be made as well as to understand the definitions behind refugees. The reasons behind migrating differ for every person and thus the definition of migration is not necessarily a straightforward answer. Thus by having several “versions” of migration, this will lead to several definitions of the word migration. Migrants who move countries due to increasing job opportunities will not have the same intentions as a refugee who is fleeing a war and thus moves between countries. While in both of these cases, we have an external force driving both sets of people, one set is not limited to these forces. These distinctions are often quite difficult to make and subjective, due to the fact that more often than not the motivators for migration are often correlated. Historically, human migration can be defined as the movement of people from one place to another with the intentions of settling, permanently or temporarily, at a new location. There are many reasons as to why people may choose to migrate. Migrants are traditionally described as persons who change their country of residence/origin for general purposes, be it job opportunities, studies and healthcare needs. Anyone changing their geographical location at will is a migrant. Refugees, on the other hand, are defined as persons who do not willingly move between countries. The reasons for their movement may be due to war within that country, or other forms of oppression. In their case we can say that there are external forces outside of their control. Even with these seemingly “easy” definitions, one can begin to sense a level of history underneath the ideas that travel deep and far. This is not simply a phenomenon that occurred overnight. There are the stories of countless humans, and a past that more often than not tends to be forgotten. Just as history should not be used to take our present for granted, so too should the present; the now, be challenged. So, too, will this application seek to better understand the foundations that were laid and the evolution that followed.

Foucauldian discourse analysis would highlight there is no precise “moment” in time and space where something is affected and/or changes. Rather, it is a continuous series of events that compound on each other much like dominoes would. One piece falling causes another piece to fall in turn. This, then, leads to any event that is seen in our now, which is the reason that before we are even able to tackle the concept of “migration”, one needs to first address the dominoes that fell before that.

Migration, for this reason, has always been a contentious topic. The domino pieces, in our case, would be formed of entirely separate and yet interconnected events and situations. The political aspect, job opportunities, economical opportunities; the list can go on indefinitely. This starts to form the idea of different areas and fields being interlinked. One can, therefore not talk about migration in general without having to also tackle the aspect of politics. “We tend, instead, to be interested in what happens when people draw on the knowledge they have about language, knowledge based on their memories of things they have said, heard, seen, or written before to do things in the world: exchange information, express feelings, make things happen, create beauty (…) This Knowledge- a set of generalizations, which can sometimes be stated as rules, about what goes where in a sentence“[2]. Language in general and words, more specifically, affect the way that we view the reality around us. Our reality is comprised of many different interacting instances; these interactions do not exist within a vacuum and thus it is necessary to understand how these interactions affect our reality. Language, much like humanity, changes and evolves over time. Foucault would reject that we are using the past to “fix” the present, rather we are using the past to understand what where we have come from and what had led us to be in the position we are now. It is for this reason that we cannot fix the now as, from a certain point of view, there is nothing to fix. We can only learn from it, “The product of a Foucauldian genealogy is not an I; it is a we“[3].

Throughout history, there have been documented accounts of migration, however, with the advent of globalization, this had led to ease of travel, to a convenience of travel as well as, more importantly a necessity for travel. If we are to fully understand the concept of migration and its evolution over the millennia, we would need to understand human history in general. “Migration”, as a strict concept, can be traced back to the human movements that took place with Homo erectus leaving Africa and migrating into Eurasia about 1.75 million years ago. This sparked the global migration which would eventually lead to Homo sapiens arriving in the Americas around 20,000 years ago. While this is a very broad and brief overview of what would otherwise be a vast human event, the aspect of migration or movement as a human trait, therefore, can be said to be one that has existed for millennia which would lead us to evolve into the modern humans we are now. Hence being able to understand the historical aspect of our past can better help us understand the human progression through time. The idea of humans migrating and moving through time and space has been a concept as old as humans have existed on the earth, however, following the technological advancements made following the Industrial Revolution, this facilitated the movement and travel. Virtually overnight, travel was reduced vastly and this was met with more need and desire to travel. Thus over the years our definition of “migration” has undergone a gradual and noticeable change. While the concept of migration has been around since the first humans leaving Africa, the arrival of the Industrial Revolution halfway through the 18th century, in a sense, kick-started our modern idea of migration between countries. However, the question that can be asked is to why the Industrial Revolution can be considered a turning point to our definition and idea of migration? The “modern” notion of migration arose through the technological advancements that took place during the 18th century “As in its influence on general political and societal developments like the Arab revolution (…), the impact of technology on migration is undeniable. It facilitates the flow of people across the planet and the formation, growth and maintenance of diaspora communities and family ties.“[4]. However, before we can begin to understand the impact that the Industrial Revolution had on the larger scale, it is crucial to understand the time period that this would have been taking place in. During the 18th century the Atlantic Slave Trade would have been at its peak, “Europe’s impulse to conduct a trade in Africans enjoyed an ideological underpinning in the theory of mercantilism (…) drawing raw (especially tropical) materials from the colonies (…), and keeping skilled artisans at home while supplying the colonies with low-priced unskilled labour.“[5]. This form of migration, as had been discussed earlier, was a non-voluntary form of migration. This was forcefully relocating a huge amount of people away from the countries and areas of origins “between 1492 and 1820 slaves accounted for more than three-quarters of the 11.3 million migrants to the Americas, while Europeans accounted for less than a quarter (..) Yet it was not until 1880 that the cumulative flow of Europeans to North America exceeded that of Africans.“[6]. Migration, by the 18th century definition, was about the movement of slaves within the Atlantic Slave Trade. Imperialism and Colonialism was the order of business, with the new colonies in North America, Central America and South America in heavy demand for “low-priced unskilled labour” counted on involuntary migration. Slaves accounted to almost 8.5 million migrants heading for the Americas. As seen in the excerpt, it was only until the 1880s when Europeans began to exceed that of Africans in terms of movement and migration. This coincided with the Industrial Revolution. To put it somewhat briefly, the Industrial Revolution can be argued to be the beginning of the notion of globalization. While the notion of globalization was not used by name, the core idea had already began to take form. The world became smaller, events that would take days and maybe weeks to accomplish could suddenly be done within much shorter time spans. The harnessing of electricity, steam power, the radio etc made life in the 1900s much easier and less unpredictable. As is most well known, the Industrial Revolution was characterized by its factories, “The growth of new communities shifted the balance of population from the South and East to the North and Midlands; enterprising Scots headed a procession the end of which is not yet in sight; and a flood of unskilled, but vigorous, Irish poured in, not without effect on the health and ways of life of Englishmen. Men and women born and bred on the countryside came to live crowded together, earning their bread, no longer as families or groups of neighbours, but as units in the labour force of factories; work grew to be more specialized; new forms of skill were developed, and some old forms lost. Labour became more mobile, and higher standards of comfort were offered to those able and willing to move to centres of opportunity.”[7]. Thus some main distinguishing factors were eventually made in regards to migration: labor migration, refugee migration and urbanization. The Industrial Revolution proved to be one of the clearest examples of urbanization, or in other words, the movement of people from the countryside to the more urban and industrial life. Thus the definition of “migration” began to change slowly over time. The population slowly began to move towards the uncertainty of rural life to a more certain and secure urban lifestyle. Migration now soon took on the mantle of “security” and “job opportunities”. The rural lifestyle was one rife with uncertainty especially in financial security. The concept of being able to have a stable and “secure” job, as safe as a factory could be, was an overwhelming temptation which led the more and more people leaving the countryside for this stability. The definition of migration, therefore, took on a role of advancements, of progress and of prosperity. There were incentives to migrate. This is seen through the fact that the majority of migrants were leaving for the “New World”, or in other words, the Americas. The work market was booming just prior to the 1900s. This was the start of the “American Dream” years before it was first coined in the 1930. This was the incentive that was the prime motivator for migration during the periods of uncertainty. Why remain here when I could move to America for a chance at the big wins? This consensus kept growing past the abolishing of the Slave Trade from Africa to the Americas and thus evolved through into the basis of prosperity.

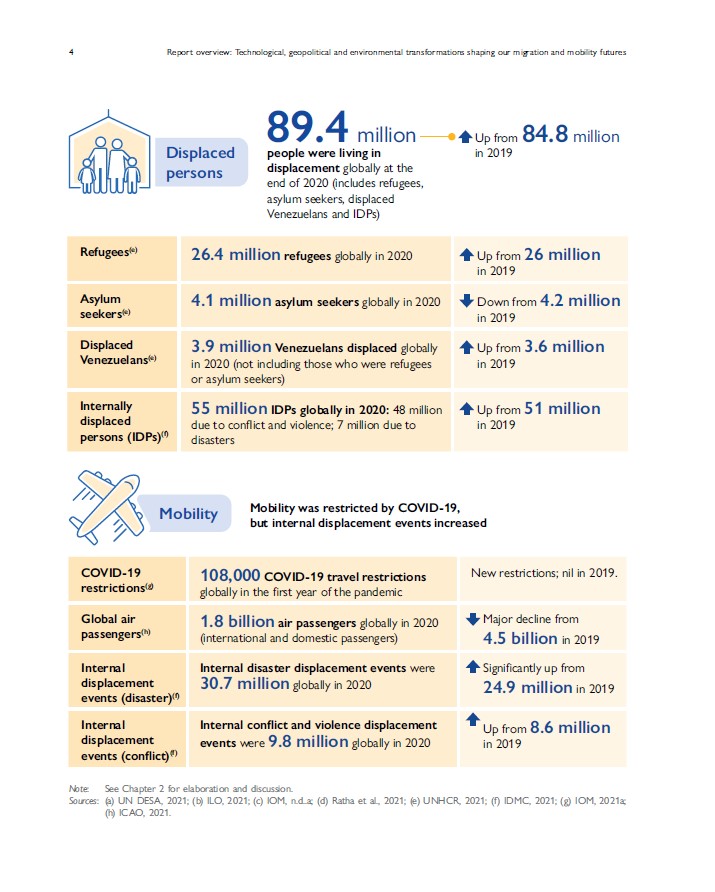

“Foucaultians are not seeking to find out how the present has emerged from the past. Rather, the point is to use history as a way of diagnosing the present.“[8]. Through the ideas of Foucault, we will attempt to understand the reason as to why our present is the way that it is. Our present and thus the “now” is rooted in history, our collective history. We will not be seeking to find out how the present has emerged from the past as that is creating a fixed point in time; rather we will attempt to understand the now through the lens of our history. Foucault’s Discourse Analysis implies history and archaeology, it implies historical context and a form of relationship between the past and the present “History should not be used to make ourselves comfortable but rather to disturb the taken-for-granted.“[9]. I had attached the painting by Norton called “Unveiling The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World” for the reason that it depicts the nature of the topic and nature of Migration especially post Great War in the 1920s-1930s. As mentioned above, we need to make a distinction between freely migrating and forcefully moving due to external forces. The Great Depression was a turning point on the global scale as the stock market crash led to widespread unemployment as well as an out of control inflation. This created a domino effect that would lead to the installation of the Nazi Party in Germany and the start of World War 2. However, even the very reason as to why the Great Depression occurred was itself a consequence of a series of events that had been taking place within it’s history. World War 1 had devastated most of Europe physically, morally and economically. It would come to no surprise that there would need a considerable amount of time, effort and especially money to aid Europe and the different countries get back to it’s feet. The damage had been done and there was need for a period of rebuilding. This caused stress on the economy and the market “Many years after it ended, former President Herbert Hoover offered an elaborate explanation of the Great Depression, complete with footnote references to the work of many economists and other experts. “THE DEPRESSION WAS NOT STARTED IN THE UNITED STATES,” he insisted. The “primary cause” was the war of 1914-18.“[10]. Europe was left reeling in the face of devastation and destruction that was left in it’s wake. This lead to many local Europeans embarking across the Atlantic towards the United States of America for a new life, a new beginning. The immigrants that had left Europe following the Great Depression did so out of a desire to find a better life, better opportunities. By being able to understand the history of migration, it’s origins and its effects, we can also begin to better understand our now. Migration and the definition of migrating changed. It become an idea of growth, chance and change “With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!“[11]. There was an idealized concept of migration. The idea of moving to new lands in order for a better future was not misplaced nor was it in bad faith. And this, throughout history, has been heavily influenced by the politics and the political world. As one can see from the stats provided by the UN, migration has become just that: Statistics. Cold hard facts that are not able to fully represent the true scale that is migration. There are stories, human being, lives and livelihoods that are stakes here.

Foucault’s focus on the process of history and its effect on our present is important in being able to understand the changes that occur. As my colleague[12] put it that there is opposition, struggle, and overturning between different systems of moral evaluation. “Genealogy means both the value of origin and the origin of values.”[13]. In other words, genealogy accepts the changing of history. It is an unavoidable aspect of our reality. While going over the different articles and reports published by the UN, I couldn’t help but get the emphasis that was being made on the inevitability of migration. In one way or another, people will migrate. Whether it is for work, whether it is out of necessity, whether it is forced or whether it is for studies people will inevitably migrate. While it still does not account for a majority of the human population “The current United Nations global estimate is that there were around 281 million international migrants in the world in 2020, which equates to 3.6 per cent of the global population. This is a small minority of the world’s population, meaning that staying within one’s country of birth remains, overwhelmingly, the norm. The great majority of people do not migrate across borders; much larger numbers migrate within countries“[14], there are still a vast number of people moving. This will not end and thus the definition and concepts behind migration will continue to ever evolve.

| Areas of Origin 2020 | |||

| Destinations | High-Income Countries | Middle-Income Countries | Low-Income Countries |

| Africa | 826,988 | 6,901,516 | 14,942,739 |

| Asia | 3,944,722 | 63,034,099 | 14,463,195 |

| Europe | 28,629,152 | 51,983,186 | 4,736,532 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 3,360,068 | 10,099,478 | 905,926 |

| North America | 11,674,525 | 40,777,887 | 2,186,124 |

| Oceania | 4,327,564 | 4,599,668 | 185,156 |

Table 1: “Data on the number of Migrants from Origin to Destination” – UN Data.

| Areas of Origin 2005 | |||

| Destinations | High-Income Countries | Middle-Income Countries | Low-Income Countries |

| Africa | 744,240 | 4,861,426 | 9,137,069 |

| Asia | 3,076,170 | 41,615,425 | 5,767,057 |

| Europe | 19,126,353 | 41,249,398 | 2,036,165 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 2,809,069 | 3,665,444 | 359,807 |

| North America | 11,588,371 | 30,263,788 | 1,232,499 |

| Oceania | 3,541,011 | 2,257,198 | 73,026 |

Table 2: “Data on the number of Migrants from Origin to Destination”- UN Data.

Table 3: “Data on the number of Migrants from Origin to Destination”- UN Data

| Areas of Origin 1990 | |||

| Destinations | High-Income Countries | Middle-Income Countries | Low-Income Countries |

| Africa | 704,277 | 3,603,629 | 10,143,177 |

| Asia | 2,603,992 | 33,699,503 | 8,990,265 |

| Europe | 14,121,836 | 33,197,699 | 1,246,003 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 3,090,763 | 3,314,634 | 256,604 |

| North America | 10,200,981 | 13,791,243 | 490,582 |

| Oceania | 3,287,108 | 1,352,291 | 15,817 |

From the data that the UN had provided, it can be seen how the number of migrants through the world had continued to grow throughout the years, throughout different geographical areas. The three tables show the quantity of migrants that had been moving over a 15 year span. From the data it can be seen how the rate of migration is steadily increasing.

[1] Kendall and G. Wickham: “Using Foucault’s Methods”, SAGE Publications, London, 1999, pg. 18.

[2] Johnstone: “Discourse Analysis“, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, USA, 2018.

[3] T. May, “The Philosophy of Foucault“, Acumen, New York, 2014, pg. 67.

[4] P. Oiarzabal and U.D Reips: “Migration and Diaspora in the Age of Information and Communication Technologies”, Routledge, London, 2012, pg. 1334, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1369183X.2012.698202.

[5] J.A. Rawley, “The Transatlantic Slave Trade”, Thomson-Shore, Inc, USA, 2005, pg. 212.

[6] J.P. Ferrie, T.J. Hatton, “Two Centuries of International Migration, Elsevier B.V, 2015, pg. 54.

[7] T.S. Ashton: “The Industrial Revolution 1760-1830“, Oxford University Press, Ely House, London, 1948, pg. 1-2.

[8] Kendall & Wickham, pg. 18.

[9] Kendall & Wickham, pg. 18.

[10] J.A. Garraty: “The Great Depression“, Anchor Books, New York, 1987, pg. 4.

[11] D. Lehman: The Oxford Book of American Poetry“, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006, pg. 184.

[12] Alwin.

[13] G, Deleuze,: “Nietzsche and philosophy“, Hugh Tomlinson, The Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, 2002, pg. 2.

[14] António Vitorino, “World Migration Report 2022“, International Organization for Migration, Geneva, Switzerland, 2021, pg. xii.

Will

Over a long period of history, China, as the most populous country in the world, has undoubtedly sent a large number of migrants to other places. Even today we cannot estimate how many Chinatowns are located outside China. When these migrants enter a new social system and cultural environment, it is difficult to quickly grasp and adapt to the local social norms and rules as a new discourse system, because prior to this, they were situated within their own Chinese social and cultural discourse system. For those Chinese immigrants, the former one, we can call it as ‘external discourse’, while the later can be named as ‘internal discourse’. Faced with this problem, Chinese people often form specific communities within themselves in a strange environment. But what makes the church one of the most important organizational forms of this community? In this application, I will use Foucault’s discourse analysis method based on the collected statements, observations, and interviews over a period about the establishment of the Chinese church in the Netherlands, to reveal that it plays a mediating role between the two sets of discursive power.

First, I will examine how the external discourse of Chinese migrants is formed outside of China in the current state of it in western world. Then, I will examine the formation of discourse within the Chinese immigrant community, which I called ‘internal discourse’. Finally, I’ll base it on some characteristics of the Chinese church and introduce some outputs of the interviews todiscuss the relation between power and subjectivation to conclude that the church is the result of the interaction between the two discursive power systems. Before starting, what needs to be clarified here is that Foucault’s method is not a fixed system. He adopted different methods in each work. In addition, due to the size of this application it may appear less specific at some points. I will quote directly from my interviews in the arguments.

-

External Discourse on Chinese Identities

Western civilization is the dominant discourse power in the entire world. Before we delve into our subject, we need to consider this as an unquestionable empirical fact. While we can argue that other civilizations around the world have made significant contributions to the development of human history, it is through actions such as the Age of Exploration, the slave trade, the establishment of colonies, and the imposition of their civilization as a general norm in modern society, that Western civilization can be seen as the direct creator of modern society, which is why it is the dominant discourse power. For example, when we view Western attire as a symbol of identity, refinement, culture, and a general societal norm, the clothing of other ethnicities often becomes characteristic customs, which further illustrates that who holds dominance in the discourse of the contemporary world. With more advanced and systematic social operations and ways of life, Western countries have been the primary destination for global immigration for nearly a century. However, this is not the native land of immigrants; they enter into such a social system as outsiders. Therefore, for immigrants, modern Western society represents an ‘external discourse’.

In the external discourse, immigrant communities exist as objects. This is evident in news media reports, government policies, and even charitable organizations providing assistance and support to foreign immigrants; all of which indicate that immigrant communities are “objects to be dealt with.” Chinese immigrants are no exception to this. Despite slogans of internationalization and the advancement of modern civilization towards homogenization and the erasure of differences, in the presence of visibly Asian faces, Chinese individuals in places where Caucasians are the natives and the predominant demographic have long struggled to escape differential treatment. Even though Chinese individuals abide by the law and pay taxes just like everyone else, the actions of real-life society are not entirely governed by legal statutes. The discourse of the majority with native status undoubtedly holds greater power than the demands of minority groups. This is why most members of Chinese churches are involved in managing their own businesses; they understand that they may not be able to compete for managerial or subordinate positions, and they may have experienced unsuccessful attempts in the past. Therefore, businesses such as Chinese restaurants are not only a result of external societal factors but also a reflection of their own choices, it is their best way to exist under the external discourse. At the very least, while native people may not want outsiders to share resources, they are still willing to embrace a certain freshness that other cultures bring to their lives, such as Chinese cuisine. Therefore, in the external discourse, Chinese immigrants are a uniquely objectified group.

2. The Formation of Internal Discourse

For the Chinese immigrants, in comparison to the external discourse they face, they have organized their own ‘internal discourse’. This internal discourse may initially consist of the social customs and norms they bring from China, but when they become immigrants, this discourse system undergoes changes to help them adapt to their new living environment. Even though they are rarely influenced by traditional Chinese feudal ethics and have already been provided with a modernized environment in China to live in before their migration, when they move as a minority to the Western world, they are still most likely to communicate and interact with are other Chinese immigrants, rather than locals. This is because they are both implicitly objectified by the external discourse, excluded from participating in western discourse formulation, and cannot quickly be integrated into the new discourse system as individuals.

Here, I make a distinction between two kinds of individuals: relative individuals and absolute individuals. Relative individuals refer to individuals in relation to local Westerners; absolute individuals refer to individuals who are completely socially excluded and isolated. Before forming some forms of immigrant community, every Chinese immigrant exists as a relative individual in relation to the external discourse. This is because they originally do not come from within the external discourse, meaning they did not grow up in Western society. However, each individual Chinese immigrant shares a set of Chinese social and cultural discourse systems with each other, and they all face the situation of being outside the Western discourse. Therefore, they will spontaneously form some form of community to cope with the challenges of the external discourse. Otherwise, they will face the danger of becoming absolute individuals: not only being rejected by Western society but also unable to find a community to belong to. This would make it impossible for them to survive. Thus, the identity as a relative individual is a result of the two discourses: on the one hand, Chinese people themselves want to maintain a certain uniqueness, and often this uniqueness is something that cannot be changed and must be preserved because of the influence of Chinese cultural discourse. The ideas and educational methods of their elders to some extent will continue to be passed down. On the other hand, due to obvious racial differences and the tendency for Chinese people to marry within their own community, their descendants will also maintain the same external characteristics of being Chinese. This will prevent them from escaping this uniqueness as Chinese. At the same time, the result of this “relative individual” is also what the host country desires: although the government nominally prefers complete assimilation, however, in reality, due to the obvious distinct differences in appearance and behavior of Chinese people from locals, there is still a certain distance between the local population as a whole and Chinese immigrants. By establishing a community as relative individuals, these Chinese immigrants have formed their ‘internal discourse’.

3. ‘Chinese Church’: The Result of Interaction between Two Discursive Systems

Considering the preceding two chapters clarifying the two types of discourse, and in conjunction with the collected materials and the theory of the productivity of power, I will explore why the Chinese church has become the most effective organizational form for this community.

Firstly, it is an undisputed fact that Protestantism is a product of Western civilization and has played an undeniable role in the development of Western civilization. In contrast, China has historically been a rather secularized country. Even though its social structure has been influenced by religions such as Taoism and Buddhism, Chinese people predominantly hold a form of remembrance for their deceased loved ones and ancestors, rather than a belief in deities. This belief, if we can call it that, is more akin to a form of commemoration. Because faith does not play a significant role in the lives of Chinese people, they tend to prioritize secular life and tangible, practical values. So, what is the reason behind the Chinese migrant community in the Netherlands adopting the form of a ‘church’ as their community organization? Why not a gang or a religion other than Christianity?

When we observe that Chinese-Americans, due to their longer history of immigration, are more familiar with the legal regulations of American society compared to Chinese individuals in the Netherlands and their familiarity with Dutch societal norms. It becomes evident that Chinese communities in the United States have higher organizational strength. This is because the establishment of a more organized and clearly structured group requires more interaction between the community itself and the external world. Therefore, in such a brief period of historical development and under conditions of stricter modern migration policies, it is a good choice to establish a church. This is because the division of labour among church members, the things that are allowed and prohibited, are not as strict and clear-cut as in social institutions like schools, hospitals, or even illegal gangs. This ensures a certain level of flexibility for the community.

Furthermore, in interviews, we have found that Chinese churches do not have a clear organizational structure and division of roles. This ambiguity of power within the loosely-structured church reflects the power of the external discourse over each individual migrant. The church’s “discourse” is, in fact, a “counter-discourse” to this power. Instead of actively learning and accepting the discipline of the external discourse, each individual immigrant uses a part of the external discourse – Christianity – to demonstrate a superficial assimilation to the authorities, thereby maintaining their identity as relative individuals and avoiding becoming absolute individuals. Therefore, in these descriptions and observations, the church is nominally established as a religious organization, but its true effect is the establishment and maintenance of a community of relative individuals, rather than simply gathering those who “believe in Christ” together. This community, by using the name of ‘Christianity’, to some extent keeps excessive intervention by the external discourse on Chinese migrants at bay, ensuring that the internal discourse can continue to function and allow them to live better in the local environment.

Conclusion

In summary, the Chinese church is the result of the interaction between internal and external discourses, playing a role in reconciling the contradictions between these two distinct discourse systems. Discourse analysis emphasizes factual description and revelation rather than taking a particular standpoint. The concept of power in Foucault’s discourse is different from our everyday understanding of top-down domination and oppression. In Foucault’s view, power is a “verb”, a constantly interacting and reciprocal network of relationships. Individuals are not just recipients of power, but also the sites where power is established. Power also produces resistance to itself: when Chinese individuals are dissatisfied with the power dynamics in their place of origin and come to the Netherlands facing new power dynamics, they are subjected to the discipline of the new society. However, this discipline also generates new forms of power, such as the church community, demonstrating the productive nature of discursive power.

Philosophical Exercises

1. Place yourself in the early modern period in the Netherlands. What factors you think played a role in changing the view of migration?

2. The next time you read an article in the newspaper or watch a program that discusses migration in the Netherlands. Try to note which factors dominate that article or program. Write these factors down and think of other factors that the article or program have not taken in consideration.

3. Try to find an article with contemporary migration as its topic on Facebook or Twitter. Drudge through the comment section and ask yourself the following: is the conflict (which you will inevitably find) rooted primarily in (‘ideological’) convictions or in perceptions of the situation? How do you think these differences arise?

4. Pick a recent piece of media consciously involved with the contemporary migration debate and watch closely. Can you identify and make explicit one or more than one implicit idea of citizenship?

5. When you travel to other countries or are already in the host country as a migrant, how do you establish connections with the locals?

6. When you are faced with two different social power systems, try to use the method of distinguishing internal and external discourse systems to analyze how the two systems interact.

7. With the concept of dominoes having some cause and effects with issues in the present, think of other issues where you would be able to trace back the dominoes and see how they change over time.

8. What is the history of immigration within your own country? How has this history affected the way your country is now?

- Stolen from: https://iep.utm.edu/foucault/#H1 ↵

- Deleuze, Gilles: "Nietzsche and philosophy", Hugh Tomlinson, The Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, 2002, pg. 2. ↵

- Foucault, Michel: “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History.” In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, edited by D. F. Bouchard. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pg. 140. ↵

- Deleuze, Gilles: "Nietzsche and philosophy", Hugh Tomlinson, The Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, 2002, pg. 2. ↵

- Foucault, Michel: “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History.” In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, edited by D. F. Bouchard. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pg. 142. ↵

- Foucault, Michel: “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History.” In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, edited by D. F. Bouchard. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pg. 144. ↵

- Johnstone: "Discourse Analysis", John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, USA, 2018, pg. 18. ↵

- Kendall and G. Wickham: "Using Foucault's Methods", SAGE Publications, London, 1999, pg. 18. ↵

- Kendall and G. Wickham: "Using Foucault's Methods", SAGE Publications, London, 1999, pg. 18. ↵