2 Phenomenology

Lisa van Dolder; Simone Visser; and Femke Stevelmans

Introduction

By Lisa van Dolder, anonymous contributor, Simone Visser, Femke Stevelmans

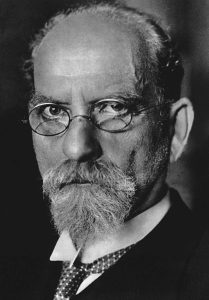

Phenomenology is a philosophical method which is aimed at studying conscious, first-person experience. It allows us to study how phenomena (events and objects) appear to us. Phenomenology arose as a movement in the 20th century. Edmund Husserl is typically seen as the founder, though some thinkers before him could be seen as practising phenomenology. As a separate discipline however, phenomenology entered the stage in the 20th century. Besides Husserl, key thinkers in the phenomenological tradition are Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Philosophy of mind, a branch of philosophy that looks into the nature of the mind and its relation to the body, sometimes also makes use of phenomenology.

©Dooder and ©pixabay via canva.com

A central concept within phenomenology is ‘intentionality’: our conscious experiences are always directed towards something. For example, whenever I go outside during spring, I hear the birds sing. This experience is directed towards an object, namely, birds. Without this directedness, this experience would merely be an empty ‘I hear’. Similarly, all of our conscious, first-person experiences are directed towards something. The way in which objects appear to us in our experiences is central to the study of phenomenology.

So what, exactly, does ‘doing phenomenology’ look like? Contrary to other philosophical disciplines like ethics and epistemology, phenomenology focuses on our subjective, conscious experience.[1] It looks into the structures of our experience and the way we generate our knowledge. For example, phenomenology might analyse how a couch appears to us. Rather than appearing as a static object separate from us and our environment, one could conclude that we see the couch as a place to sit.

A key tool in phenomenology is the phenomenological reduction. This involves setting aside one’s presuppositions and prejudices to enable a more pure experience. By using this tool, we make sure that no theoretical ideas influence the way we experience. Philosopher Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, called the belief that the world exists independently of us the natural attitude. Based on the natural attitude, we make certain theoretical assumptions about reality, and as a consequence, we fail to recognise how experience shapes the way we learn and act. In order to do phenomenology, we should suspend the natural attitude. Interestingly, this also means that empirical science should be set aside when doing phenomenology because it presupposes that the world exists independently of our perception. This process of getting rid of the natural attitude is what Husserl calls epoché.

Another key tool in phenomenology is the eidetic variation or reduction: the process of imagining variations of an object, comparing these variations, and analysing what features remain in all variations. Through this process, one comes to know an object’s essential features. These features are essential, because without them, the object would not be what it is. By appealing to our imagination, this method is based on intuition, as well as epoché. After all, the imagining and comparing of an object’s variations should not be clouded by presuppositions and prejudices.

A central element of human experience is the contact with other people. The concept of intersubjectivity refers to the relation between at least two experiencing subjects. Through this notion, different phenomenological philosophers have analysed different aspects of human interaction. Central terms regarding intersubjectivity are empathy and apperception.[2] According to Husserl, empathy lets us recognize the subjective and conscious experience of other persons. Empathy is possible because we are able to distinguish ourselves from everything external to us through the experience of our lived body. That is, through the way we move our bodies and recognize and experience this body as our own. Apperception allows us to recognize other persons as experiencing and conscious beings, even though we cannot actually see inside their minds and experience their consciousness ourselves. We recognize them as subjects, but because we can never enter their consciousness and experience their point of view as our own, they are experienced as others.

Phenomenology is a philosophical method which has sprouted a variety of philosophical works. Not only is the study of the key thinkers’ works still relevant today, but their works are also useful in other philosophical disciplines like philosophy of mind and feminist philosophy. Even outside philosophy, phenomenology is sometimes used in qualitative research in scientific disciplines such as psychology and social sciences. In the remainder of this section, we will discuss what the phenomenological method looked like for Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty. In addition, we discuss how phenomenology is used in philosophy of mind, feminist philosophy and social sciences.

Philosophical Exercise

Exercise 1: Try to see if you can perform a phenomenological reduction yourself: look at an object in your surroundings. Suspend all beliefs about said object. How does the object appear to you? What about it makes you believe it exists?

German Phenomenologists: Husserl and Heidegger

As said before, Edmund Husserl is considered to be the “father” of phenomenology as both a philosophical tradition and as a philosophical method. Although not the first to use the term, he both popularized and expanded the movement to be what it is today. Coming from a mathematical background, Husserl wanted to make philosophy into a hard science. He thought that the best way to do so was by putting aside the natural attitude, so we could get to the phenomena, to the essence of our conscious experience. Alongside the natural attitude, Husserl came up with many other tools and concepts to help us get to the bottom of human consciousness, as can be seen above. Although his phenomenological successors have criticized some aspects of Husserl’s phenomenology, they are still heavily influenced by and indebted to Husserl and his ideas.

One of the phenomenological successors that has been heavily influenced by Husserl, but also gave it his own spin, is Martin Heidegger. Instead of focussing on consciousness like his predecessor, Heidegger preferred to study Being. In his most well-known work Being and Time, he attempts to answer the question ‘what is the meaning of Being?’ or, what does ‘to exist’ mean? He does so by phenomenological reduction of human existence, with humans, characterized as Dasein, as the starting point. The goal for Heidegger is thus to find out what the necessary and foundational grounds are for human existence.

Not-being-at-home is an example of one of the foundational aspects of being-in-the-world. Heidegger deems for instance the phenomenon of not-being-at-home to be one of the necessary Existenzialen of Dasein, which means that is a necessary foundational part of being-in-the-world. This phenomenon is described by Heidegger by way of the phenomenological reduction, i.e. he gives a first-personal explanation of a phenomenon that tries to be free of judgment.

French Phenomenologists: Sartre and Merleau-Ponty

The phenomenological tradition spread from Germany and Austria to France. In France, philosophers Sartre and Merleau-Ponty formed their own versions of phenomenology. In his main phenomenological work Being and Nothingness (1943), Sartre puts forward his view about human experience. To Sartre, intentionality is consciousness of an object, rather than the presence of objects in consciousness. What does this mean? Well, suppose I smell a rose. This means that I am conscious of the rose; the rose is a phenomenon in my consciousness. Contrary to Husserl, Sartre does not believe the rose to actually be in my consciousness. Rather, it is simply a consciousness of the rose that exists in the world.

Sartre was an existentialist: he was concerned with questions centering around human existence. He believed that humans are radically free. Even if our options are limited, Sartre believed that we are always free to make choices and shape who we are by our actions. In making choices and doing things, humans define themselves. Notably, Sartre did not stick to strict philosophical conventions to put his ideas forward. Instead of treatises or papers, he wrote plays and novels, and he did not refrain from giving his philosophical thinking an ethical and political dimension. For example, Sartre believed that some people try to escape from their radical freedom by assuming social roles and values, thereby distancing themselves from their choices. He called this phenomenon “bad faith”: people pretending as if they did not have any other choice. Instead of assuming social roles and values, humans should live authentically by living in accordance with their radical freedom.[3]

Contrary to Husserl, Heidegger and Sartre, French philosopher Merleau-Ponty interacted extensively with the sciences. Rather than treating the body as a static object, which was conventional in the sciences at that time, Merleau-Ponty highlighted how perception and the experience of the body shapes our experiences. He developed his own phenomenological theory which takes perception as central in experiencing the world, through connecting the experience of our body to the experience of the world around us. His main phenomenological work is Phenomenology of Perception (1945). By shifting focus to the role of the body in experience, Merleau-Ponty informed his theory with insights from experimental psychology. A central idea in Merleau-Ponty’s thinking is that the I, as a subject, is a body engaged in actions in the world.[4] Thus, Merleau-Ponty shifted the focus to the way our bodies form the starting point for exploring the world around us.[5] Merleau-Ponty formulates the central phenomenological concept of intentionality in this context: activities of the body are intentional.

Contemporary Phenomenology

Phenomenology continues to play a significant role in contemporary philosophy, influencing and contributing to various philosophical discussions and areas of inquiry. After the phenomenological movement, started by the philosophers mentioned above, the use of phenomenology nowadays is less centered around a main philosopher, but more spread out to different fields of study. In all these different fields, phenomenology offers a way of thinking focused on experience, consciousness, and interpretation and therefore has greatly influenced the way in which these sciences have evolved. Nowadays, phenomenology isn’t only talked about in science, but scientists and philosophers are doing phenomenology[6]. Let’s dive deeper in the fields of study that phenomenology has greatly influenced.

Philosophy of Mind

Phenomenology serves as both a philosophical approach and a method within the philosophy of mind. As a method, phenomenology offers a structured and systematic way to investigate the nature of consciousness, subjective experience, and the mind. This was argued to be necessary by some philosophers who objected to the completely functional view of cognition.[7] The phenomenal aspects of the mind were put aside in the cognitivist view which resulted in a method of research on the brain and its functions as if the brain was a computer. By using the phenomenological method of the philosophy of mind, the experience and consciousness of an individual were included again.[8]

Feminist Phenomenology

As mentioned before, phenomenology offers a method for investigating the lived experiences of individuals. Following the phenomenological tradition, our experience of the world is influenced by our inner conceptions and personal history. We could argue that gender is one of these inner conceptions of self. Therefore, gender influences how we experience the world around us. The famous philosopher Simone de Beauvoir examined how women’s identity and experiences are shaped by their societal role as “the other” to the standard of being a man. To gain a more complete insight into how the world is differently experienced based on gender, scientists can use the phenomenological method to better understand gender-related experiences. This has been done in research on gender equality, social justice and recognition of marginalized voices.[9] Feminist phenomenology is therefore a new but very relevant topic of research where the phenomenological method has been used to gain new perspectives.

Social Sciences and Humanities

This is an emerging area of study where phenomenology is applied, but very relevant to the topic of migration. In the phenomenology of social sciences and humanities, the focus is on the lived experience through culture and language. Alfred Schutz has described how individuals interpret and make sense of their social world through the lens of phenomenology.[10] This has been a leading method in understanding how individuals create meaning in social interactions. Phenomenology has also made significant contributions to the field of psychology. Psychologists like Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow drew on phenomenological principles to develop humanistic psychology, which emphasizes the importance of subjective experience, self-actualization, and personal growth.[11] Humanistic psychology has had a lasting impact on psychotherapy and counselling, promoting a more client-centred and empathetic approach to helping individuals.

Applications

Radical freedom, diversity and integration

By Simone Visser

Integration

When talking about migration, the topic of integration often comes up. When people migrate to another country, it is often assumed that these people should integrate in their host society. Without integration, immigrants might struggle to find their way in society. Finding a job, pursuing an education, chatting with one’s neighbours, receiving health care, finding and consulting companies and agencies for services will all become easier if one learns a country’s language and understands its culture, at least to some extent. In addition, different cultures coming together can raise tensions between people. For example, tensions might arise when a group of immigrants believe that women are not allowed to pursue higher education, whilst the host society’s people believe this to be a violation of women’s freedom.

In The Netherlands, if an immigrant comes from a country outside the EU and countries other than Switzerland, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway, if this immigrant is older than 18 and younger than the retirement age and if one has a residence permit, then one is required to take an integration exam. There are exceptions however, for example when one already lived in The Netherlands for 8 years as a kid or teen and went to school. International students or expats aren’t required to take an integration exam either. All other immigrants are required to take an integration exam within 3 years of their arrival in The Netherlands. The exam contains a language test, a knowledge test about Dutch society and a test about finding work and participating in Dutch society. By passing this exam, one is officially integrated into Dutch society.

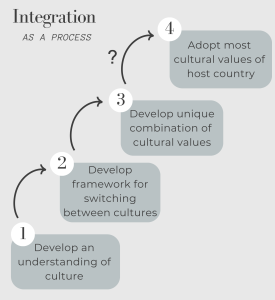

But what does ‘integration’ actually mean? Usually, we understand integration as the process of becoming part of the country one moved to. But what exactly does this look like? When has one successfully become part of a country? We can imagine different ways of interpreting the concept of integration. Consider, for example, the following interpretations of integration:

- Developing an understanding of the host country’s cultural values, but without abandoning one’s own cultural values. Continuing to endorse one’s own values, but understanding one’s differences in relation to the host country.

- Adopting new cultural values whilst also keeping cultural values one held before. Developing a framework for switching between cultural values depending on the context.

- Adopting some new cultural values, making these your own by mixing it with your own cultural values. A new set of values is formed.

- Abandoning one’s own cultural values, adopting the host country’s cultural values, learning its language.

There does not seem to be a clear-cut interpretation of integration, or how integration should proceed. Perhaps it could be said that at least some of these interpretations of integration are different levels of integration (as illustrated in Figure 2). To illustrate, someone might have moved to The Netherlands to find better working opportunities. First, they start off by learning some Dutch words and phrases, as well as getting to know different aspects of Dutch culture. Still, they hold onto their own values and beliefs. By finding a job and creating a small network of Dutch people, they develop a deeper understanding of Dutch culture and make some Dutch values their own. After a few years, they have developed their own unique mixture of Dutch values and values they held before migrating. However, we might question whether integration often proceeds to the abandonment of one’s own cultural values, and the adoption of the host country’s cultural values. This would involve separating from all values one was brought up with, something I deem very difficult, if not impossible.

Still, there might be people who expect immigrants to become Dutch in the sense that they expect immigrants to only exhibit their endorsement of Dutch cultural values. Others might be satisfied with immigrants learning the Dutch language and understanding Dutch cultural values and traditions. In this way, it seems that different people hold different beliefs concerning migration. Both immigrants and a host country’s citizens might have different expectations concerning to what extent integration should proceed. What can phenomenology, and specifically, Sartre’s existentialist phenomenology teach us about integration?

Radical Freedom & Bad Faith

A central question for Sartre was directed at the identity of the ‘I’. Whenever I speak of myself, what is ‘I’ referring to? Though he did not explicitly mention it, we can see that the method of eidetic variation helped Sartre analyse variations of the ‘I’. He found that all answers to this question refer to something external.[12] To illustrate, I could say that I am a baker, or that I have blonde hair, or that I am Dutch. But these things refer to something external of me. Moreover, many aspects with which I try to identify myself are subject to change. Instead of identifying the ‘I’ with an unchangeable essence, Sartre identifies the ‘I’ with the things we do. To elaborate, the ‘I’ is constituted by a sequence of acts of consciousness, which is always directed towards something external to itself. There is no subject behind consciousness, which means that I only consist of the things that I do; the things I perceive, think, imagine, wish, feel and desire.

This idea led Sartre to distinguish between “being-in-itself” and “being-for-itself”.[13] Objects, such as chairs, are “being-in-itself”: being a chair is its identity. Humans, however, are not fully defined or constituted by something like “being a cook”. Beings-for-itself do not have a stable identity like chairs do. Our consciousness is always directed toward something external, and this consciousness is constituted by our acts. Humans, then, are “being-for-itself”. In this way, humans are radically free. This does not mean that we are ethically allowed to do anything we want, nor does it mean that we have superpowers to be everything we want to be. Radical freedom means that we always make choices. Our options may be limited, but we are still free to choose what we want. Through the choices we make, we shape our identity, but never does this identity become essential and stable.

As mentioned before, Sartre injected this view with an ethical and political dimension. Many people, he noted, try to escape their radical freedom. Being radically free is a hard pill to swallow: it means that I am the only person responsible for my choices. And in making choices, I am creating a certain image of humanity for which I have chosen. Through my decision, I am communicating that I believe this decision to be the right one for everyone that would be put in my situation. When we become aware of this freedom and responsibility, we feel anxiety. Some people try to escape this feeling of anxiety by distancing themselves from this freedom. Sartre calls this phenomenon “bad faith”.[14]

People act in bad faith if they pretend that their situation is determined by things external from themselves. For example, we often hear people claim that they wished to have done certain things in their life, only to regret not having done so later. Maybe you even have claimed such things. “I have always wanted to become a firefighter, but my life went in another direction.” The problem is not that one was not able to realise this dream, but that one acts as if their ‘fate’ simply befell them; that had their circumstances been different, they could have become a firefighter. According to Sartre, this person escapes their radical freedom by distancing themselves from their responsibility to make choices.

Only through recognizing one’s radical freedom, one acts authentically. One should not acquiesce in one’s situation and believe that one does not have other choices, because this is not true. Instead, one should recognise that the only reality is that of doing, and that we shape ourselves through our actions. In life, we are always making decisions, as it is simply impossible not to make any decisions. Even if one does not make a decision, one still makes the decision not to make a decision. Sartre writes in his essay Existentialism is a Humanism (1946) that when making moral decisions, we are like artists. A painter like Picasso has created himself through painting the things he painted. Similarly, we create ourselves through the things we do.

Freedom and Diversity

What does Sartre’s theory of radical freedom tell us about integration? When talking about migration and integration, there are two parties involved: the immigrants and the host country’s citizens. What is of interest here, is whether we can claim that both parties act in bad faith or if they act authentically. Of course, it is important to note that I make a general analysis in this section. I am not stating that ‘all immigrants do X’ or that ‘all citizens of this country do X’. This obviously does not do justice to the complexity and diversity of actual cases of immigration and integration. Rather, this section serves to provide a framework for applying theoretical tools to integration in a more practical context.

Let us take a closer look at integration from the perspective of an immigrant first. When moving to a different country, immigrants might want to start a new life in another country. They might want to attain this country’s nationality by taking, for example, an integration exam. They learn about this country’s cultural norms, values, traditions and language. Still, they bring their own cultural norms, values, traditions and language with them. Immigrants might struggle to balance these, or find a way to unite sometimes contradicting beliefs. Others might not be actively occupied with integrating in society. In addition, some groups of immigrants or refugees face discrimination, negative stereotyping and xenophobia in their new country. In face of these problems, they might for example question whether they should hide their religious or cultural identity.

When looking at the perspectives from the host country’s citizens, we encounter many different opinions concerning immigrants. Some people might not welcome immigrants at all, whilst others welcome them with open arms. Others, perhaps, might be more selective regarding what immigrants they accept. Fact remains that immigration is a reality in many countries, and people have to interact with immigrants in some direct or indirect way. Some people might hold anxious beliefs concerning immigrants. They might, for example, worry that they ‘take away’ job opportunities or take up housing space. Others might be ok with immigrants, as long as they adhere to the host country’s culture and do not exhibit deviating cultural norms. They might expect immigrants to abandon their own beliefs and cultural values and not speak their native language in order to blend in a host country’s culture.

In short: both from the perspective of immigrants and from the perspective of a host country’s citizens, there are many differing expectations of what integration should look like. With sometimes conflicting expectations, alongside problems like xenophobia that arise in this context, we should ask: to what extent should integration ideally proceed? What Sartre’s theory of radical freedom tells us is this: we are all always free to choose. The decisions we make shape who we are. We should not pretend that our identity is set in stone. In the debate surrounding integration of immigrants, some people pretend that they have an essential identity. To try to escape their radical freedom, some immigrants might stick to the values and beliefs they were brought up with and pretend that they cannot change these values and beliefs. Similarly, a host country’s citizens might do the same, and expect that only immigrants change. Both thereby block the possibility of learning from each other, thereby creating fear for or anger towards each other. Both flee their responsibility to make decisions. In short, they act in bad faith.

What does acting authentically look like in the context of integration? When different people with different (cultural) backgrounds come together, we see an excellent opportunity to become aware of the other. We learn new things, and we might want to choose to abandon some of our cultural values or beliefs, to form new ones, and to continually make decisions that shape ourselves.[15] In The Netherlands, there are several initiatives that stimulate people from different backgrounds coming together, learning about and from each other, adopt new ideas and shaping new beliefs. For example, Vluchtelingenwerk Nederland (Refugee Work The Netherlands) organised an event to stimulate conversation between immigrants and Dutch people. The event, called Bakkie doen? (Want to have a cup of coffee?), involves refugees sharing a cup of coffee with passersby, often leading to interesting conversations. Conversations with a cup of coffee diminishes the distance between refugees and Dutch citizens, creates space for empathy and understanding and thereby opens the way for both parties to actively engage with their own beliefs and identity.

Initiatives like Bakkie doen? help to stimulate learning from and about different cultures. Especially for those who act in bad faith by acting as if they cannot change themselves, participation in such initiatives might be fruitful. Of course, one needs to keep an open mind and be receptive to be able to learn from others. In turn, this might involve allowing feelings like anxiety to arise. By being open, receptive and by recognising that you are free, one enables the constant and dynamic shaping of one’s identity. An important first step is to practise epoché: by becoming aware of one’s presuppositions and beliefs, and by setting them aside, one enables a more open and receptive experience, eventually leading to embracing one’s radical freedom. Sartre’s theoretical and phenomenological tools encourage us to be authentic and actively choose our actions, beliefs and values.

Philosophical Exercises

Exercise 2: Remember the last time you felt like you had only one choice and you could not do something else. Try to remember how you felt at the time. Was it a pleasant feeling? Or did you feel constricted and limited? Now, try to think whether you actually had only one choice. What other options were perhaps present? Having considered this, do you agree with Sartre that we are radically free?

Exercise 3: Search for local initiatives focused on integration and cultural diversity. Sign up for an event and before going, be mindful of your own beliefs, values and norms you adhere to. Write down what things you consider as an essential part of your identity. After attending the event, look at this list again. Do you still feel the same way about your beliefs, values and norms? Do you feel more certain about them, or did some of your beliefs weaken?

Hatred Against Asylum Seekers in The Netherlands

By Lisa van Dolder

Introduction to the Problem

In The Netherlands, a troubling undercurrent of animosity persists towards asylum seekers, a sentiment that has not only permeated societal discourse but has also had a profound impact on the country’s political landscape. The manifestation of this animosity has led to a polarisation of political preferences, particularly in the realm of asylum policies, to the extent that it has even led up to the fall of the cabinet due to disagreements on the matter. However, amid these heated arguments, it’s crucial to look for new and creative ways to promote understanding, compassion, and a kinder view of people who come to the Netherlands seeking safety and help.

Phenomenology, as a philosophical framework and method, offers a unique lens through which we can examine and address this deeply ingrained hatred. By delving into the subjective experiences, perceptions, and emotions that underlie these sentiments, phenomenology provides a nuanced understanding of the origins and manifestations of this animosity. It invites us to explore the lived experiences of both asylum seekers and those within the host society, unveiling the intricate interplay of cultural, social, and psychological factors that contribute to this divisiveness.

In the following paragraphs I will take two concepts of phenomenology and explain how we can apply these to a part of migration that I described above. Hopefully, after reading these paragraphs, you will be able to use phenomenology as a method to better understand your own thought processes and the lived experiences of others, as well as having a better understanding of the roots of this intrinsic hatred towards asylum seekers among the Dutch population.

Applying the Phenomenological Method

Epoché

Epoché is one of the main concepts that we discussed in the method description. It is a part of the phenomenology theory as developed by Husserl. In the development of A part of doing epoché is bracketing. By using bracketing we can try to eliminate our own preconceived opinions on certain objects, experiences and opinions. When we apply the method of epoché on asylum seekers, we can try to bracket certain preconceived conceptions of their experiences. We could ask ourselves “Why did they come here?”. Many people in The Netherlands assume that asylum seekers often come here for our economic welfare. The few asylum seekers that are fleeing war, from Ukraine for example, are more than welcome, but other people that flee the Middle-Eastern countries are only here for money. At least, that is what a part of the Dutch population thinks the reasons are for people to seek asylum in The Netherlands. However, their opinions could cloud their capability to see the facts. As Husserl stated, the idea that there exists a world independently from our reality needs to be eliminated. He named this the ‘natural attitude’ and by eliminating this distinction, we have to acknowledge that our experiences influence our reality.

Data published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) shows that only half of all the people that request asylum in The Netherlands get accepted for a residence permit. This means that these people have valid reasons for fleeing their home country and not all asylum seekers are blatantly accepted. In the natural attitude, we could see these numbers as facts in the world that do not apply to our reality, since the world exists independently from us. By getting rid of that natural attitude, we have to accept these facts as our reality and accept that we have theoretical ideas that influence how we look at this data. To do so, we have to bracket all feelings, opinions and previous experiences with and about the facts that are presented to us.

When getting presented this data from UNHCR, someone could have something to say about these data that might undermine the validity of it. For example, that the UNHCR is an untrustworthy source and therefore the data cannot be true. While doing phenomenology, this thought can be bracketed, which takes away the thought about the data. After this the data can be considered again without this theoretical idea. Might another thought pop up that is linked to a feeling, opinion or previous experience, we should bracket that thought as well. After bracketing all thoughts that can prevent us from seeing the truth, we can now evaluate the data without preconceived notions. Husserl would say that this is the only way to honestly experience something, like these data, and have true and realistic thoughts about it.

The Other

Another way to apply phenomenology as a method to tackle the problem of hatred against asylum seekers, is by using Simone de Beauvoir’s conception of “the other”. This concept highlights the importance of recognizing the unique experiences and perspectives of a certain group of people as distinct individuals rather than abstract categories. De Beauvoir famously argued that in a patriarchal society, women are often perceived as “the other” in relation to men. She stated that women are frequently defined in opposition to the normative category of man, and this “othering” of women is a means of objectification and creating dependance to the man. De Beauvoir also used the concept of “the other” to address the existential experience of alienation that individuals can feel when they are objectified, oppressed, or marginalised by society. These same dynamics can be found when looking at asylum seekers in relation to citizens.

When looking at news articles about asylum seekers, we can recognize language that is used to describe or refer to asylum seekers as abstract categories, instead of individuals in need. The words “asylum seeker” are often used in relation to them being a disturbance, that the country is full and them committing sexual assault. These are negative notions that describe a big, but also strongly varied group of people. Thinking of the concept of “the other” they are portrayed as being very opposite from the ‘normal’ citizens. A distinction often isn’t made between reasons for people to come here, their age, gender, religion and country of origin. Or in other words, the lived experiences of the people that seek asylum in The Netherlands, often don’t match the theoretical ideas people have about them.

The NOS, the largest news organisation in The Netherlands, interviewed people who were for or against asylum seekers. A pattern that can be found is that people are often afraid of religions that are not ‘Western’, like Islam, and cultural habits that are not accepted in The Netherlands, like men treating women as less of a human and child marriages. However, not all asylum seekers are religious and carry those feared beliefs. The opinions of the interviewed people are probably influenced by how society has treated asylum seekers as “the other” which led to a (harmful) generalisation and objectification. They have to sleep in big rooms with hundreds of people and are regularly transferred to other shelters as if they are inanimate objects, not human beings. Which makes it easy not to think of them as people that are like us, but just as “the others”.

De Beauvoir’s philosophy suggests that recognizing the “otherness” of individuals should lead to ethical considerations. She argued that acknowledging the otherness of individuals should encourage empathy and respect for the autonomy and subjectivity of others. It challenges individuals to consider the consequences of certain policies and their impact on those who are “othered”. Understanding how society often refers to asylum seekers as “the others”, in the same way as women have been viewed in patriarchal societies before the feminist revolution, can show us why our attitude towards asylum seekers may not be ethical. When we view asylum seekers as individuals with unique needs, instead of “the others” in regards to the citizens, we are more likely to support policies that prioritise their rights and well-being.

What Value Does Phenomenology Add?

Applying phenomenological methods to societal issues can give people new insights on how to perceive the situation. In this application, I evaluated the use of epoché and the concept of “the other” in examining the hatred of Dutch people against asylum seekers. This is necessary since wrong assumptions about a sensitive topic like this can result in harmful policies against asylum seekers.

Epoché, as developed by Husserl, can show someone how their thoughts and feelings about certain information influence their experience of this information. If people wish to examine their thoughts on this information unbiased, they can use bracketing to take away preconceived notions about the information that influence their reality. However, if somebody is not aware of the risk of theoretical ideas influencing their experience, it is hard to use bracketing to make them experience the information unbiased.

The concept of “the other”, as used by Simone de Beauvoir, can open the conversation on how we view and treat a minority group as a society. Trying to understand that asylum seekers are still individuals that came here to find shelter, can take away the alienating and generalising effect of treating a group as “the others”. Analysing if we are indeed thinking about a group of people as a different kind of human than ourselves can lead to ethical conflict. Generally, people don’t see an individual as a different kind of human, but a group can be more easily deprived of basic human rights. Therefore, this topic in phenomenology can also be more easily used to help other people become aware of how we view marginalised groups in society.

Philosophical Exercises

Exercise 4: Think about all the asylum seekers that have come to The Netherlands in the past year. What preconceived notions come up in your head? Can you bracket these and set them aside? Now read a news article on asylum seekers. Continue to bracket all the existing opinions that you have on this topic. Does this help you to clearly see only the facts? Did your thoughts on asylum seekers change after bracketing your preconceived notions?

Exercise 5: Imagine a group of asylum seekers in The Netherlands. What do you instantly think of? Do you perceive them as people that are alike you, or are very different from you? Often in marginalised groups, we look at people as abstract concepts and not as individuals. This is created by our attitudes towards them as “the other”. Try to think about them as individual people with such urgent needs that they decided to leave their home and come to The Netherlands to seek help. Do you still feel the same, or did your perception on how different they are from you change?

Migrants in Media: Looking Them in the Face

By Femke Stevelmans

Introduction

Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995) was a French philosopher, most known for his work in Jewish philosophy and phenomenology, as well as his method of relating ethics to metaphysics. Oftentimes, he’s placed within the phenomenological tradition as two of his biggest influences were prominent figures within this tradition: Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. Levinas’ own philosophy makes use of the phenomenological method pioneered by Husserl but his philosophical focus is similar to Heidegger’s: the body and the environment, and its influence on the experience of the perceiving subject. The distinguishing feature of Levinas’ philosophy is the fact that he operates from an ethical perspective, stemming from his interest in not only the embodiment of the subject but also the embodiment of others: the people the subject encounters. This intersubjectivity then forms the basis of many of our ethical principle.

The encounter with other people, this face-to-face with the Other, only makes sense if we start with the ‘I’, the subject. Like Husserl, Levinas thinks we cannot think of our experiences in a detached and abstract way: we are always a subject. Thus, we cannot start from anything other than subjecthood in our analyses. When we take away everything else and start from the subject (thus doing a sort of phenomenological reduction), we find a kind of ethical obligation that only appears when we encounter the Other. This obligation only appears when the encounter is a face-to-face. When we see the face of the Other, we see vulnerability and humanity. We recognize that the Other is a subject also and that we have a complete and infinite responsibility to this person. For Levinas, we need to look the Other in the face and see that they are someone completely different from us, another subject that we can never possess, like we can other things in the world. The face of the Other places an immense burden on the subject by commanding them to be at the service of this face and commands one thing: do not kill me (Totality and Infinity). This commands underlies the entirety of Levinas’ ethics in general. When we encounter the face, we are commanded to act responsibly and ethically – to not kill the Other in their vulnerability. But we can never fulfil this responsibility as it is infinite: we always need to do more.

But this infinite responsibility highlights another important aspect of Levinas’ philosophy: the asymmetrical relation with the Other. As we will see later, Martin Buber also argues for a subject that is oriented towards other people. But he argues that the relation with the Other is one of symmetry and reciprocity, one where difference and power don’t play a role. Levinas disagrees with this: I am infinitely obliged to the Other I encounter and I cannot cancel this by appealing to their infinite obligation to me. The self will always remain more responsible for the Other. They can never merge, nor be equal.[16]

Portrayal of Migrants in Media

Migration is a hot topic in international media, because it is usually very relevant and also quite controversial. Despite it being generally recognized that the media should portray things as accurately as possible, the media still circulates misinformation about this topic, as well as using terms that generally evoke negative feelings or ideas, like using the word refugees when talking about migrants in general. Another example of misrepresentation is using the term ‘illegal asylum seeker’, when seeking asylum is a human right.[17] According to a study done in 2018[18], European media generally underrepresents migrant groups and when represented, they are portrayed in a negative or even stereotypical way: as economic, cultural or criminal threats. As Re:framing Migrants in European Media, a pilot project aiming to change the current media narratives around migrants and refugees in Europe, states:

“(…) refugees and other migrants who came to Europe in the past decade frequently ended up being portrayed as one-dimensional characters, as “others” on a simplistic binary of perpetrators and victims. Their own stories, perspectives and opinions, as multi-faceted person’s dreams, fears, friends and family are rarely shared.”

In short, migrants are often reduced to statistics, stereotypes and other generalizations – usually (but not always) with a negative connotation and leading to dehumanization of the people in question. These negative stereotypes can lead to fear (e.g. of crime) and polarisation, as well as influence policies and public opinion.

Levinasian Analysis

One major problem with the fundamental organization of the media is of course that it is a medium: we never actually have a direct face-to-face encounter with the Other, only a portrayal of the other person. Because we don’t encounter the face ourselves, we don’t see the vulnerability of the other person. And this vulnerability, even if it can be communicated through an article or video, is frequently neglected: migrants are portrayed as threats, burdens or problems. When we don’t encounter the face and don’t see its vulnerability, we forget that these individuals need compassion and understanding too.

Another problem is that the media, through sensationalism, generalization and dehumanization, actively obscures the face of the Other. By emphasizing certain traits or other aspects these migrants have in common or portraying them purely as statistics, it objectifies them and makes us forget that they are individuals with their own faces. The media makes them into faceless entities and causes us to forget that they are subjects in their own right and thus deserve to be treated as such.

Lastly, by not encountering the Other and their face, we are not ethically commanded to do anything. We cannot feel responsible for a stranger through the media because the appeal of the face is lost – as a result, we don’t feel like we have an ethical commitment to the Other and feel okay with the idea of them suffering. We are completely detached from the real experience of the migrants and have no moral responsibilities regarding them because we cannot or do not see their face.

Another important thing is that Levinas also felt that when we refuse to look at the face of the Other, that is where violence begins. It is actually a form of violence to avoid looking at the face and to refuse to acknowledge your moral responsibility to that person.[19] By avoiding the face of the migrants, through their media portrayal, we’re actually committing a sort of violence, one where we refuse to look at the individuals we’re talking about and refusing to admit that they are subjects too, not objects.

When we embrace Levinas’ idea of the face, we can analyse and question the narratives that reduce subjects to objects or other generalizations like stereotypes or statistics. Thus, encouraging a more nuanced and respectful approach that better represents reality. Additionally, we can get a different and more critical perspective on the media portrayal of immigrants, as well as see what we can do to portray them more authentically and in a way that honours our ethical responsibility to them. One of the ways things could be done is by letting the immigrants tell their own individual stories, to emphasize their individuality and vulnerability. Another way is through emphasizing empathy and compassion in their stories, by presenting immigrants as fellow humans facing tragedy and adversity instead of faceless entities. Other related things are avoiding dehumanizing language, using correct definitions and challenging or acknowledging biases within journalism itself. These are just a couple of ways we can represent the experiences of people more authentically and in ways that humanize them.

Philosophical Exercises

Exercise 6: Think of the latest article or video you have seen about immigrants. Did this piece of media portray the face of the immigrant well, or were they reduced to a faceless mass? How did the article or video achieve this result?

Exercise 7: What other strategies can the media employ to avoid obscuring the face of the people they portray?

Not-being-at-home, existential reasoning in migration

By anonymous contributor

Introduction

In Heidegger’s Being and Time, it is not the mind that is prior, but being, which in turn makes it the case that mind and world ought not to be seen as initially separate, but as fundamentally interactive (Heidegger, 2010). This interaction between mind and world is captured in one of the core concepts of Being and Time, namely that of Dasein, which is always already being-in-the-world. One cannot be without World, and the World is constitutive for how one is. The way that the world around us is, has a huge impact on the way that we are. Though Dasein and World have this reciprocally interactive and constitutive relation, and thus are tied in a very crucial way to each other, this tie is not without some form of tension. As soon as one is part of the World, or how Heidegger calls it, as soon as Dasein is ‘thrown’ into World, it becomes inauthentic, which without going into detail, can be explained as to stop being, or be hindered in realizing, your innermost self, and instead becoming caught in trying to fit into the mold of the averageness of the others. Now this is ‘always already’ the case, this can only cease to be so from the starting point of being inauthentic.

From this existential phenomenological viewpoint where the world around you has this huge influence on you, but is also in tension with realizing your innermost self, it is not hard to draw the connection to migration. Because what is it that causes people to migrate voluntarily? What are the steps in choosing to migrate for existential motivation? And more precisely, what do these existential motivations to switch from one place of living to another look like in a concrete setting? I think it always fundamentally involves some sort of lack that the world around you is providing which you hope to find elsewhere in order to flourish. But what does this lack consist of, and where does it come from? How is this tied to Heidegger’s notion of not-being-at-home (Unheimlichkeit)?

I aim to answer these questions by first giving an explanation of what this not-being-at-home means, second, giving a case study of Christian missionaries, who I argue can be taken to experience not-being-home in choosing to migrate, and third, tying the two together to see how this alters how we should view existential migration.

Not-being-at-home

Heidegger’s notion of not-being-at-home is not a concept particularly relating to migration, or to feeling at home in a certain place per se. Rather, it pertains to a more general underlying condition involving our experience of being-in-the-world. Still, I believe not-being-at-home can be applied to migration by offering a different, and existential way of looking at what causes one to migrate, by relating it to this more general condition of being-in-the-world.

According to Heidegger, we are ‘always already’ not-being-at-home, meaning that as soon as we are born, we are already necessarily in this particular state of being, though in our everyday lives we do not realize that this is the case (Withy, 2021). Not-being-at-home then, is an Existenziale, i.e. a foundational, necessary part of being-in-the-world. It is therefore not the case that one person is born being-at-home, and another is not; it is a shared condition which, primordially, comes alongside being-in-the-world.

But what is it more precisely to not-be-at-home? It is to experience this uneasy feeling of exclusion from the familiar, due the realization that oneself and the environment are interrelated in a way which prevents self-actualization (Withy, 2021). Here, there is tension between the self, constituted by the established position, world, and framework which one is born into, which in its daily life has been accepted as the familiar, and the prospect of a better future for this self, which is unfamiliar.

Person and world then, are crucially interconnected, but not harmoniously. A person does not choose to be shaped by its environment in the way that it has, yet at the same time, this person has to take responsibility for being this way. To take on this responsibility is to go beyond this being a mere product of environment, to go beyond the familiar, and instead trying to realize the true self which is unique, and inside all of us, waiting to be realized in unfamiliar territory (d’Agnese, 2018).

It is not hard to see that the way our environment has impacted us is in some way or another, not ideal. This is the case in the sense that the environment we are born into usually does not contribute to, or is not set up for, becoming our true selves. For instance, it is not without reason that there is a widespread notion that children at a certain point in their lives ought to stand up against the absolute authority of their parents, and instead should figure out for themselves how they can give their lives meaning. For if they would completely conform to their parent’s ideals, they would forego fulfilling their own destiny; being stuck in the familiar without realizing is detrimental to self-actualization. As for the responsibility aspect of not-being-at-home, no matter how badly your environment was, or is impeding your potential to flourish, it is still always you that has to take responsibility for your actions, and it is still always you that has to face the consequences of these actions.

Of course, the environment in which one lives, i.e. the world which one inhabited, is also not a fixed thing, it is open to displacement, and without a predefined end; it is in a constant state of becoming. This constant state of becoming is something we at the same time enact, and have to endure. In the experience of this state, we see the ‘abyss’, which is the past and its problems, behind us, and pursue our ideal future. It us up to us to realize this ideal future, while also not succumbing to the abyss; we have to endure not-being-at-home, and attempt to pursue beyond this being.

I think this pursuit of an ideal future could involve a voluntary change of your place of living, due to there being something to this not-being-at-home which is crucially connected to the place where you live. Such is the case for people who choose to migrate for existential reasons, which can involve having this call within oneself to go to another country (Maddison, 2006).

This is a phenomenon that is often found within Christian missionaries. They feel ‘called’ by God to go to another country and to do missionary work. Such people view their homes as a place they ought to leave behind to become who they really are. In what follows, I illustrate how such instances could be taken to be related to not-being-at-home, and from this I will argue that not-being-at-home aids us in understanding existential migration.

Case Study

‘I WANTED TO KNOW HIM BETTER’

When Christ revealed Himself to me in 2006, I longed to make Him known to others as well. At the time I did not recognize that as my calling. I simply wanted to know Him better. I joined YWAM and was sent to Greenland. During my time there, I saw God’s power at work and felt his calling to serve the people of Greenland. This calling stayed with me for six years. Then my wife received a dream about Greenland and we decided to visit Greenland. We had peace while being there. We asked the Lord for a sign from outside our family. During our travel home, an unknown man approached us on the plane, asking us what we had done in Greenland. I told him that we wanted to live there to do mission-work. He was very moved and told us that this had been his exact prayer for many years! To us, this was God’s confirmation. In 2014 we moved to Greenland and we praise God as we see Him at work.’ (Globe Mission, 2021)

This is the short story of a man who received a call to become a missionary in Greenland. Missionary work usually involves leaving your home for another to spread Christianity in the place you left home for. Though leaving the home is not per se necessary to do missionary work, generally speaking missionaries are viewed as people who migrate to a different country.

I identified a general step-by-step structure to the process of becoming a missionary that I think is analogous to the process of self-actualization that the concept of not-being-at-home denotes, viz.:

- Being in the familiar

- Not-being-at-home

- (Doubt/looking for confirmation)

- Acceptance of the call

- Fulfillment of the call, while still in being in a state of becoming

The man from the testimony above is just one of the many cases where this step-by-step process occurs, let me identify them one by one. First, a missionary, just like anyone else, is always someone who comes from a certain environment that has shaped his or her way of being-in-the-world, so too the man from the case above. Second, the experience of not-being-at-home in this testimony is not explicitly mentioned, but I do think that we can infer it even from this very brief amount of information. Namely, when the man was staying in Greenland, he felt that it was his calling to be there, away from his familiar way and place of living. When he returned to his home country, he was being in an environment in which he could not fully self-actualize. The call to go to Greenland and do missionary work remained for six years, during which there was a tension between the self and its familiar environment. The feeling of not-being-at-home had to have occurred at least once at the beginning or during these six years. Third, there was the six year wait for the moment of confirmation, namely his wife’s dream, before choosing to leave the familiar behind. Fourth, this choice of leaving the familiar behind and go to Greenland was the acceptance of the call. Fifth, the fulfillment of the call is exemplified by the feeling of peace that was felt in Greenland, and is in an ever state of becoming by the continuing duty to spread the gospel to those who have not heard it.

The Bigger Picture

The step-by-step structure of missionary migration, and self-actualization in virtue of not-being-at-home can be extended more broadly to existential migration in general. To view migration through this lens means to see the deep need for meaning that some people experience when moving to another place. When you zoom out even further, not-being-at-home does not only play a role in this step-by-step structure of existential migration, but is also important to those who accept this existential migration in their place of living. By existential migrants entering this unfamiliar area, the area, as a place of becoming, is itself transformed, in a sense also becoming unfamiliar to the original inhabitants. By noticing this familiar becoming unfamiliar, and the uneasiness that comes with this, the original inhabitants may also experience not-being-at-home. Furthermore, it is not the case that original inhabitants were necessarily being-at-home in the first place. In fact, not-being-at-home is a foundational aspect of being-in-the-world, wherever in the world that may be. Thus by existential migration, it may be discovered by original inhabitants that their sense of belonging to the familiar is actually not based on authentic grounds, and instead perhaps could be found in the unfamiliar of existential migrants. As is the case for those who convert due to missionaries coming to their country.

References & Further Reading

d’Agnese, Vasco. “‘Not-being-at-home’: Subject, Freedom and Transcending in Heideggerian Educational Philosophy”. Stud Philos Educ 37 (2018): pp.287-300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-018-9598-3

Barber, Michael. “Alfred Schutz.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/schutz/.

d’Agnese, V. (2018). ‘Not-being-at-home’: Subject, Freedom and Transcending in Heideggerian Educational Philosophy. Pp. 287-300 Stud Philos Educ 37 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-018-9598-3

Dijkstra, Elselien. “Merleau-Ponty: wat het lichaam weet”. February 11, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2023 from https://www.filosofie.nl/wat-het-lichaam-weet-merleau-ponty/.

Eberl, Jakob-Moritz, Christine E. Meltzer, Tobias Heidenreich, Beatrice Herrero, Nora Theorin, Fabienne Lind, Rosa Berganza, Hajo G. Boomgaarden, Christian Schemer, and Jesper Strömbäck. “The European Media Discourse on Immigration and Its Effects: A Literature Review.” Annals of the International Communication Association 42, no. 3 (July 3, 2018): 207–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2018.1497452.

Filosofie Magazine. “Jean-Paul Sartre”. Retrieved October 13, 2023 from https://www.filosofie.nl/filosofen/jean-paul-sartre/.

Filosofie Magazine. “Maurice Merleau-Ponty”. Retrieved October 19, 2023 from https://www.filosofie.nl/filosofen/maurice-merleau-ponty/.

Gallagher, Shaun. Phenomenology (2nd ed. 2022, Ser. Palgrave Philosophy Today). Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11586-8.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time: A Translation of Sein und Zeit. SUNY Press.K, 1996.

Käufer, Stephan, and Anthony Chemero. Phenomenology. John Wiley & Sons, 2021.

Lévinas, Emmanuel. Het Menselijk Gelaat. Ambo/Anthos B.V., 1969.

Madison, Greg. “Existential Migration”. Existential Analysis, 17.2 (2006): pp.238-60 https://www.gregmadison.net/documents/MigrationEA.pdf

Manen, Michael van, and Max van Manen. “Doing Phenomenological Research and Writing.” Qualitative Health Research 31, no. 6 (May 2021): 1069–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323211003058.

Missionary Testimonies – Globe Mission. (2021, 24 juni). Globe Mission. https://www.globemission.org/en/discover/calling/missionary-testimonies/

Nooteboom, Bart. “Levinas: Philosophy of the Other.” Palgrave Macmillan UK EBooks, January 1, 2012, 162–84. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230371019_8.

Oksala, Johanna. “What Is Feminist Phenomenology? Thinking Birth Philosophically.” Radical Philosophy 126 (January 1, 2004).

Reynolds, Jack and Renaudie, Pierre-Jean. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, s.v. “Jean-Paul Sartre” (Summer 2022 Edition), ed. Edward. N. Zalta. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/sartre/.

Rijksoverheid. “Moet ik als nieuwkomer inburgeren?” Retrieved 24 October, 2023 from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/immigratie-naar-nederland/vraag-en-antwoord/moet-ik-als-nieuwkomer-inburgeren.

Rogers, Carl R. “Toward a Science of the Person.” Journal of Humanistic Psychology 3, no. 2 (April 1963): 72–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/002216786300300208.

Sartre, Jean-Paul Charles Aymard (2000). “Existentialisme is humanisme”. In De uitgelezen Sartre. Lannoo/Boom, 2000 (article originally published in 1946).[20]

Smith, David Woodruff. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, s.v. “Phenomenology” (Summer 2018 Edition), ed. Edward. N. Zalta. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/phenomenology/.

Smith, David Woodruff, and Amie L Thomasson. Phenomenology and Philosophy of Mind. Oxford: Clarendon Press ; New York, 2011.

Smith, Joel. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, s.v. “Phenomenology”. Retrieved October 5, 2023 from https://iep.utm.edu/phenom/.

Varela, Francisco J, Eleanor Rosch, and Evan Thompson. The Embodied Mind : Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mit Press, 2016.

VluchtelingenWerk Nederland (June 26, 2023). “Bakkie doen? groot succes”. June 26, 2023. Retrieved October 26, 2023 from https://www.vluchtelingenwerk.nl/nl/artikelen/nieuws/bakkie-doen-groot-succes.

VluchtelingenWerk Nederland. “Wat is inburgering?” Retrieved October 26, 2023 from https://www.vluchtelingenwerk.nl/nl/wat-wij-doen/begeleiding-bij-taal-en-inburgering/wat-inburgering.

Wikipedia contributors. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, s.v. “Phenomenology (philosophy)”. September 13, 2023. Retrieved October 13, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Phenomenology_(philosophy)&oldid=1175276667.

Withy, Katherine. “Uncanniness (Unheimlichkeit)”. In The Cambridge Heidegger Lexicon, ed. Mark A Wrathall, pp.789-792. Cambridge University Press eBooks, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1017/9780511843778

- Wikipedia contributors, "Phenomenology (philosophy)". Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. (ed. September 13, 2023). Retrieved October 13, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Phenomenology_(philosophy)&oldid=1175276667. ↵

- Shaun Gallagher, Phenomenology (2nd ed. 2022, Ser. Palgrave Philosophy Today, 2022). Palgrave Macmillan Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11586-8 ↵

- Reynolds, J. and Renaudie, P.J. (2022). Jean-Paul Sartre. In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2022 Edition). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/sartre/. ↵

- Filosofie Magazine, "Maurice Merleau-Ponty", retrieved October 19, 2023 from https://www.filosofie.nl/filosofen/maurice-merleau-ponty/. ↵

- Elselien Dijkstra, "Merleau-Ponty: wat het lichaam weet", February 11, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2023 from https://www.filosofie.nl/wat-het-lichaam-weet-merleau-ponty/. ↵

- Michael van Manen and Max van Manen, “Doing Phenomenological Research and Writing,” Qualitative Health Research 31, no. 6 (May 2021): 1069–82, https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323211003058. ↵

- Francisco J Varela, Eleanor Rosch, and Evan Thompson, The Embodied Mind : Cognitive Science and Human Experience (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mit Press, 2016). ↵

- David Woodruff Smith and Amie L Thomasson, Phenomenology and Philosophy of Mind (Oxford: Clarendon Press ; New York, 2011). ↵

- Johanna Oksala, “What Is Feminist Phenomenology? Thinking Birth Philosophically,” Radical Philosophy 126 (January 1, 2004). ↵

- Michael Barber, “Alfred Schutz,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2023, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/schutz/. ↵

- Carl R. Rogers, “Toward a Science of the Person,” Journal of Humanistic Psychology 3, no. 2 (April 1963): 72–92, https://doi.org/10.1177/002216786300300208. ↵

- Filosofie Magazine, "Jean-Paul Sartre". Retrieved from https://www.filosofie.nl/filosofen/jean-paul-sartre/. ↵

- Reynolds, Jack and Pierre-Jean Renaudie, "Jean-Paul Sartre", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), retrieved fromhttps://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/sartre/ ↵

- Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre, “Existentialisme is humanisme”, in De uitgelezen Sartre (2000. Article originally published in 1946). Lannoo/Boom. ↵

- Of course, one can also choose not to abandon one's cultural values or beliefs. Still, it is important that one actively makes this choice, rather than pretending that one did not have a choice. ↵

- Bart Nooteboom, “Levinas: Philosophy of the Other,” Palgrave Macmillan UK EBooks, January 1, 2012, 162–84, . ↵

- https://www.unhcr.org/nl/media/verslaggeving-over-vluchtelingen/ ↵

- Eberl, Jakob-Moritz, Christine E. Meltzer, Tobias Heidenreich, Beatrice Herrero, Nora Theorin, Fabienne Lind, Rosa Berganza, Hajo G. Boomgaarden, Christian Schemer, and Jesper Strömbäck. “The European Media Discourse on Immigration and Its Effects: A Literature Review.” Annals of the International Communication Association 42, no. 3 (July 3, 2018): 207–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2018.1497452. ↵

- Lévinas, Emmanuel. Het Menselijk Gelaat. Ambo/Anthos B.V., 1969. ↵

- For English translations of Sartre’s article, search for Existentialism is a Humanism. ↵