1 Hermeneutics

Marijn Michels

In my high school years, I distinctly remember noticing that, when introducing a new topic to students, whether it be chemistry, history or mathematics, a lot of teachers used the “it’s all around us” approach in explaining the relevance of their preferred subject to their audience. The point that the teacher of course wants to convey is that the subject the teacher is proficient in is more familiar than the students might usually expect. Students are familiar with cooking, rolling dice and planes, but not yet necessarily well acquainted with concepts like thermodynamics, estimated probability or aerodynamics. Another point that this “it’s all around us” introduction neatly conveys is that a skilled mathematician, historian or chemist can use their conceptual tools to gain a better understanding of almost anything they are interested in, thus making it clear that in that field the only limitation is the students’ curiosity.

As is often the case, the things I picked up during my time as a high school student differ greatly from the material my teachers were trying (or told to) teach me, and as I am now entering the teaching role myself I will use this approach as I tell you about the wonderful philosophical method that is commonly referred to as ‘hermeneutics’.

If you’re anything like me from one-and-a-half year ago, you have never actually heard this word before, so let me first discuss what this word means exactly. The word ‘Hermeneutics’ comes from the Greek word “hermēneuein” meaning “to interpret”. Hermeneutics, then, can be described as the theory or method of interpretation, and it is concerned with how we form interpretations in reading, and even more generally, in experiencing the world around us.

In what follows, I will briefly examine what (philosophical) hermeneutics has been used to interpret and reflect on how these different ways of doing hermeneutics can help deepen our understanding of more topical issues.

Hermeneutics and Literature

Hermeneutics started as a method mainly used in biblical studies as theologians aimed to broaden their understanding of the Bible through rigorous reading and analysis to find out what exactly was being said. To do this, theologians focussed on trying to understand the Bible as a product of its time, they aimed for an interpretation of the sacred scriptures that was as authentic and as true to the original as possible. Hermeneutics, at first, aimed to reproduce the original meaning of the scriptures.

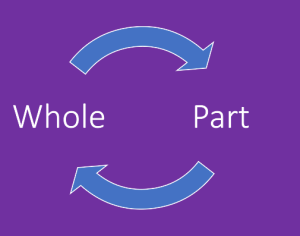

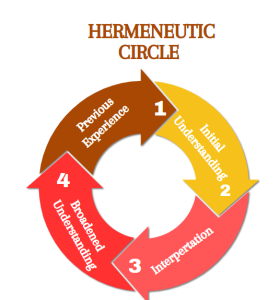

A tool hermeneuticists used to accomplish this authenticity is what is called the hermeneutic circle. The idea behind the hermeneutic circle is that an understanding of a part of a certain text changes the understanding of the text as a whole, consequently our understanding of the whole changes our understanding of what that certain part meant. Ideally, the hermeneutic philosophers claim, our understanding of the separate parts of a text and the understanding of the whole reinforce each other until everything snaps into place, and we finally have a complete understanding.

While academic hermeneuticists mostly focused on interpreting the Bible, we can apply this form of hermeneutics (and concepts like the hermeneutic circle) to a variety of texts and in doing so hopefully gain more insight as to what the intentions of the author are with various parts of a text.

An example that philosophy students are all too familiar with (because our professors occasionally remind us of it) is that all philosophical texts need to be read at least twice to be properly understood. The idea behind that advice is that sometimes specific passages only start to make sense once you understand what function they have in the rest of the text, and this can only become clear once you have a proper understanding of what the aim is of the text as a whole. When we reread a text, then, we start to place every part into that whole we’ve come to understand after our first reading, and we can then better make sense of the parts we had trouble making sense of in our previous reading.

Of course, this technique can be applied to a variety of texts, not just religious or philosophical ones. This should come as no surprise, think about all the times you’ve watched a movie in which the plot twist is way more obvious the second time, the hints that were subtle before only become blatant if you know the rest of the story.

Philosophical Exercise: Applying the Hermeneutic Circle to a Text

- Take any text (or a section of it) that you are passionate about. For this exercise it is recommended that it is a fairly short text, a poem would be ideal as it is often cryptic and has a lot of parts in which it can be dissected. Nevertheless, if you’re more passionate about a certain section in a longer text, feel free to use that instead.

- Clearly lay out what you understand the meaning of the text to be. What is the author trying to convey?

- Decide what you will be considering a ‘part’ of the text. Will you be considering every paragraph? Every sentence? Every word? (Note: all of these ‘parts’ are also made of different parts and as such can also be counted as a ‘whole’. Thus, in the same way, you can apply the hermeneutic circle to a text to understand it as a whole, you can also apply it to a paragraph or chapter of a text and gain an understanding of it by trying to understand parts that constitute the chapter or paragraph).

- Now start reading the text, asking yourself what purpose every single section has in function of the rest of the text. Ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the author trying to say in this part of the text?

- What function does that part fufill considering my understanding of the whole?

- Why would the author do that in such a way, considering my understanding of the rest of the text?

- How does this part recontextualize what I’ve read so far?

- How does my understanding of what I’ve read so far change my understanding of the whole text?

- With your renewed understanding, read the text again. Do this until you’ve formed an understanding you’re satisfied with, or until you want to stop.

Hermeneutics and Science

More recently (in philosophy standards, that is), the notion of a ‘completed understanding’ or an interpretation that is authentic has received some criticism. After, all, isn’t the very nature of an interpretation to be subjective? Furthermore, should we genuinely care about what exact interpretation the author had in mind if another interpretation is just as, if not even more, useful?

This is why in Postmodern Hermeneutics, the claim is defended that it is impossible to form an understanding of something beyond your own interpretation of that thing; in other words, it rejects the notion that there are ‘pure’ or ‘objective’ facts out there that people can get to know without some preconceived notion of what that fact means.

Upon reading this, one might worry that hermeneutics denies objectivity or the possibility of anything being true. If anything we could ever come to understand can never be more than an interpretation, would it not be impossible ever to come to know something at all?

Most hermeneuticists would rightly call out the denial of an ‘objective fact of the matter’ as unintuitive and maybe even undesirable. After all, we have fruitful discussions supported by facts all the time! Furthermore, some might even argue that this view can be harmful, after all, what is to stop people who accept the idea that there is no matter of fact from claiming important scientific ideas like vaccination or climate change are just mere opinions. Should we allow this degree of subjectivity when lives are on the line?

This is why most hermeneutics reject this primary interpretation of what the denial of ‘pure facts’ actually means. Instead, they argue that for all these things we know to be true, we only get to know these things because we have successfully looked at them through a certain perspective, a perspective that is founded on certain assumptions and previous experiences, without which we could not understand what we think to be true at all. The aim, then, is not to deny the possibility of making empirical claims, but rather to help us understand how exactly we can get to know these claims in the first place.

One such philosopher who wanted to help those interested in making empirical claims was Hans-Georg Gadamer’ who, with his work Truth and Method, tried to argue that although modern science is often concerned with being as objective as possible, the subjective nature of experience and our personal perspective are not necessarily a hindrance when it comes to doing empirical research as long as we acknowledge and criticize them sufficiently.

Gadamer’s claim, then, could be interpreted as saying we are constantly applying hermeneutics (or are constantly interpreting) anyway, whether we want to do so or not. The challenge then is to become aware of this process and to shape it in such a way that it fulfils our needs, whichever those may be.

This idea of taking a step back and considering why we think of things in a certain way is essential to critical thought. While we should resist falling back into complete subjectivity, we should also clearly be sceptical about the notions of complete objectivity we sometimes encounter, additionally, it is unwise to present our mere opinion as objective fact. If we are to accept both that no single interpretation helps us uncover the absolute truth and that not all interpretations are created equal, there is only one thing left to do: understand the world as best we can, refine our understanding constantly, critiquing the interpretations we disagree with, and letting others critique us in the same way. This is where hermeneutics can help us. According to hermeneutical theory, we are constantly expressing our interpretations of a certain state of affairs, and we can never understand or express anything more true than that.

This interpretation of hermeneutics comes with another interpretation of the hermeneutic circle. If we are not waiting for everything to ‘snap into place’, then the process described in the hermeneutic circle can better be understood as the process of forming our understanding based on our previous experience and reflecting on our previous experience in the context of a broadened understanding, as such having new material we can later reassess once we are presented with new ideas we can gain an understanding of. The challenge, then, is no longer how to see the text through the author’s eyes, but rather to learn how to interpret better, for whichever end we see fit, whether it be objectivity, authenticity or usefulness.

Philosophical Exercise: Understanding the Hermeneuticists’ Claim.

- Take any claim you take to be completely indisputably true. For example: there are atoms.

- Divide the claim into partial claims. What concepts does the claim require you to know to properly understand it? In my example, it would be at the very least atoms and a notion of existence.

- Now consider these concepts. How did you gain an understanding of these claims? Did you acquire knowledge of them via texts, verbal testimony, a graph or by direct experience?

- If you learned it in any of these ways, would you have been able to understand it without any previous knowledge? Would you be able to know what the words meant without your understanding of language, would you be able to understand a diagram if you weren’t proficient in reading such diagrams?

- Now reconsider the claim distinguished in Step 1 and make a list of all the understanding this claim relies upon (for example, my understanding of atoms, existence, the Dutch language and my proficiency in reading the letters used in the Dutch language).

- Ask yourself if you could do the same for any of the items on this list. Seemingly, my knowledge of atoms relies upon other physical facts I know about the world. Repeat the process for any claims that are more fundamental than the claim in Step 1.

- Repeat steps 1-6 any number of times, did you ever get to a claim that ended up being both completely independent on any other claim and equally indisputably true?

Hermeneutics and Daily Life

As might have become clear by now, hermeneutics is ‘all around you’ and, probably, you have already been applying it very skilfully without even knowing you were doing it! There is much more to say about how hermeneutics has been applied in a variety of fields, let me therefore finish with a few interesting cases of hermeneutics that you might consider to be more obviously ‘all around you’.

An interesting example we can use here is Heidegger’s phenomenology (which you can read about in the following chapter), which describes the hermeneutic considerations that ground our day-to-day experience as humans. Heidegger elaborated on the constant hermeneutical process by which we come to understand our experience itself. Describing our experience as an experience of ‘being-there’ (Dasein) which can be examined in and of itself.

Second, consider yourself, or more specifically your self. In The Tragedy of the Self (Sangiacomo, 2023), several conceptions of selfhood are examined, all considered through the lens of hermeneutics. This book is an interesting case because it was the introduction I myself had to hermeneutics, along with most of my peers at the university of Groningen. The book was written by one of my professors and served as the main reading for the course. In hermeneutics of the self, the idea of selfhood is examined and later deconstructed in a variety of ways.

Finally, I think Gadamer also made some wonderful points about hermeneutics and art. Consider again the criticism of the idea of authenticity, Gadamer used this notion to critique our practices concerning art (Caputo, 2018). Arguing that customs like museums, art criticism and analysis in art are often built on the erroneous notion that there is an ‘authentic idea’ that is meant to determine a work’s ‘objective value’. During our assessment of art, Gadamer contends, we should instead be more concerned with how we can find meaning in artwork in our current situation, and give proper respect to the works that prove themselves meaningful throughout the ages.

Hopefully, you now understand that wherever interpretation goes (which is everywhere); hermeneutics will follow, and that proper hermeneutic theory will help you examine just about anything you want. Hermeneutics, just like chemistry, mathematics or history is a perspective we can choose to take, but rather than examining a specific part of our experience through a certain perspective, hermeneutics chooses to examine the perspective itself, which of course is extremely important if we choose to take on these perspectives with any frequency at all.

Application: Hermeneutics and Culture Clash. Reconsidering Tradition

Traditionally, the coming together of people has always resulted in the creation of culture. Additionally, the coming together of different cultures has also resulted in the creation of entirely new or combined cultures that help us reinvent our old customs and provide us with new and exciting ways to express ourselves.

A perfect example of this is the dish known in America as ‘Spaghetti and Meatballs’ which, while considered a traditional American dish, resulted from Italian-American immigrants changing up their more traditional pasta recipes to adapt to what was more commonly available in America. The resulting dish quickly gained popularity together with other Italian foods, and thus became the symbol of the Italian-American cuisine that it still is today.

There are many other examples like this, hip-hop, for instance, is a fusion of genres (jazz, disco, funk, etc.) that originated in wildly different cultural contexts, each of which helped elevate the genre to what it is today.

Unfortunately, not all collisions of culture end up leading to the best of both worlds. Not all aspects of a culture are as simple to fuse or reshape as food or music. Nevertheless, when people identifying or adhering to different cultures come to live together (which is the inevitable result of migration), they will inevitably interact with each other, and each party will inevitably do so according to their own beliefs and convictions which are ultimately shaped by the culture they lived in previously. If these cultures do no agree on fundamental issues, this can sometimes lead to what is known as a ‘cultural conflict’ or more commonly as a culture clash.

In what follows, I will examine these cultural conflicts and argue for a way we can get ourselves in a better mindset to engage in proper intercultural debate. I will use the hermeneutic notion of Weak Thought vs. Strong Thought to showcase that, if we allow ourselves to see our own cultural perspective and the perspective as just one of many possible perspectives, it becomes easier to engage in critical discussion. Through this, I will argue that it becomes possible to ‘reconsider tradition’ and let others help us find the new norms we can apply in making a society that is more welcoming to people with different perspectives.

Defining Cultural Conflict

A cultural conflict can be defined as a situation in which conflict arrives because people with cultural backgrounds come together. This definition is still too broad for our purposes, so I will fist add a few conditions I think are important in helping us get a situation in which hermeneutics can clearly help us further.

Cultural conflict can happen on a variety of scales. Thus, the first concept we can use to qualify this definition is the distinction between macro, meso and micro levels of human interaction, commonly used in the social sciences. Cultural conflict on a macro scale would imply the involvement of larger institutions, such as a conflict between two different governments. The meso scale is commonly used to refer to smaller communities such as a football team or the students of a school. Finally, the one I am interested in is the micro scale, which involves the interactions between individual people. In what follows, I will look at the phenomenon of culture class solely through the lens of the micro scale.

Secondly, cultural conflict is also sometimes linked with violence (for example violence between people following a different religion), but this is not necessarily the case. Instead, the conception of what constitutes a conflict in this text will be more narrowly looking at non-violent cases which could reasonably be resolved if both parties would be willing to enter a proper discussion.

A culture clash or a cultural conflict for the purposes of this text will then be considered to be a non-violent conflict which is caused by people having different expectations or beliefs regarding a social situation due to the (or a) culture they associate or identify themselves with.

Consider the following example. My German friend (let’s call her Anna) and I get invited to a birthday party of another mutual friend. The party, we are told, will start at 15:00. My German friend and I get into a conflict when deciding when to depart for the party. Due to her cultural background, she values punctuality and thinks it would be rude to show up any later than the provided time. I, however, do not think showing up 15 minutes late would be a big deal, therefore I do not understand her frustration when she scolds me for beginning to prepare too late to be on time.

This is a clear example of what kind of cases I will be considering, and in my experience, it is pretty common to experience such (minor) conflicts when getting to know someone from another country. Ultimately, different cultures have different perspectives and think differently about the importance of hierarchy, tradition, openness and the relationship between the individual and the collective, and it is these fundamental disagreements that can spark a cultural conflict if people are challenged to live together despite disagreeing about these issues.

The Trouble with Tradition

What can we learn from this example? The first thing I’d like to point out is that as long as my friend and I are bickering about whether it was rude or not to show up late, we will talk completely past each other. As far as I am used to attending parties, my understanding is that there is nothing wrong with being a few minutes late, I have never known otherwise and as mentioned earlier I did not expect it possible for anyone to scold me for that. My friend, however, has been raised to believe that it is rude to attend late, and has not lived in an environment where it is not considered rude. Thus, as far as we can tell, we have both been doing it properly our whole lives.

Another important thing to note is that it is not in any way desirable or fruitful to ask either of us to completely ignore our beliefs on the matter, that is to say, in trying to live together, it is unreasonable of one of the groups to completely give up their cultural convictions to have them ‘integrate’ better into the new culture they will live together with. If my German friend and I want to maintain our friendship, it would be strange for me to tell her that we’ll arrive late on every party from now on and she better get used to it because I have been doing it in this way my entire life.

While this attitude might seem to be clearly ridiculous, this is still a common argument seen in debates surrounding ‘Black Pete’ in the Netherlands, where a common argument against making any changes to ‘Black Pete’ is that it is an authentic Dutch tradition that should not be changed in any way because this is the way we have celebrated “Santa Claus” for ages. My point is not to settle the debate here, rather I want to point out that preserving tradition simply for the sake of preserving it prevents appreciating what makes such a tradition worthwhile to begin with.

Thus, if my friend and I want to have a proper discussion about our conflict we need to create a space in which we are open to feedback on our respective beliefs and we need to reshape our conflict to be one of mutual critique rather than a case of a fundamental disagreement.

Weak and Strong Thought

This is where hermeneutics comes in. As became clear in the description of the method, earlier hermeneutics is deeply concerned with considering different perspectives on a certain thing, and as such is made to help us when there is a situation in which we are not asked to choose between one of several objective facts to believe but rather help us take on different perspectives in which each is criticizing the other.

An author who can help us better understand what exactly is often going wrong during a cultural conflict is Gianni Vattimo, who made a distinction between Strong and Weak thought.

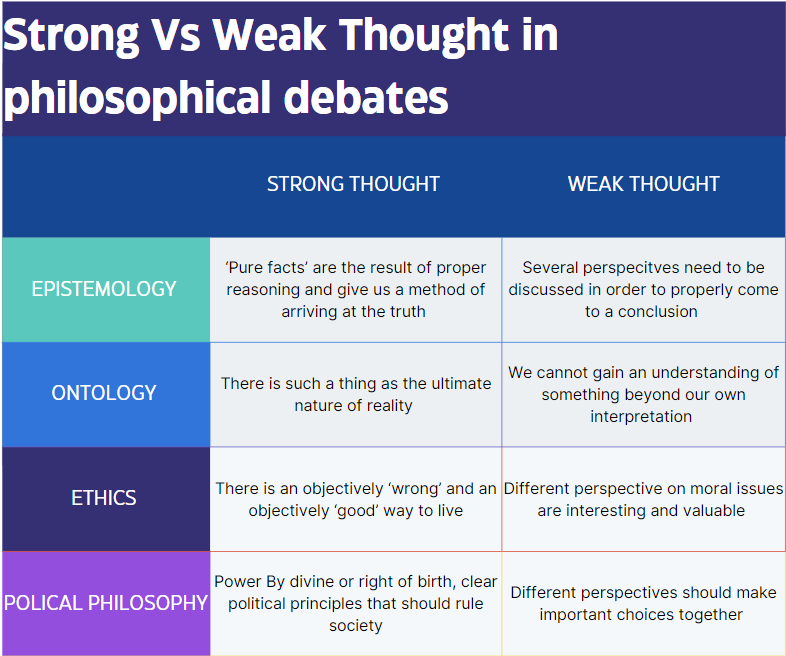

Strong thought can be associated with positions that aim to establish objective or absolute truths over a certain domain of discourse. Traditional philosophical theories such as realism and anti-realism (which are general positions in a variety of debates such as ethics, ontology and aesthetics) often tried to establish such truth. Strong thought is linked to positions that claim that facts are the result of pure reason and are unquestionably true.

Strong thought has dominated history, for instance in the belief that a religion provides the ‘ultimate truth’ or monarchies in which kings had the birthright provided to them by God to let them rule in whichever way they see fit.

Weak thought challenges the clear objective of these notions, and can thusly be associated with positions that aim to make more nuanced claims than are usually provided by positions resulting from strong thought. In the case of philosophy, this could be done by considering in which ways we are destined to be biased when making empirical claims or by being more careful when making assertions. As mentioned earlier, in hermeneutics, weak thought was developed with the denial of ‘pure’ facts and taking a shift into examining how our understanding of certain ‘facts’ came to be.

Of course, nowadays, there is more room for ‘weak thought’ than there was before. After all, faith has become more nuanced and challenged more often and most monarchies have become more democratic, whether that be through institutionalizing an actual democratic government or by changing policies such that more freedoms are granted to people living within a certain society.

Nevertheless, the common way we are taught to look at cultural norms and traditions still more closely resembles ‘strong thought’. A common phrase I often hear in talks about tradition is that “we have our way, but others do it in such and such way” and this is still a thought that is mostly on the strong side as it still establishes there is a way ‘we’ are supposed to do something. While there is definitely more awareness of the fact that cultural norms could be different, there is very little time to discuss whether our norms should be different, and this is exactly what should be at stake when engaging in proper intercultural debate.

How ‘Weak Thought’ Can Make Us Strong

Thus, if we are to create a space in which the norms by which people originating from different cultures are to live together can properly be discussed, we first need to weaken our notion of cultural norms and traditions that ground the discussion in the first place. If we are to truly commit ourselves to creating a new environment of shared views and new communal traditions, we have to be willing to see our traditions as just one of many possible traditions and open them up to feedback and critical analysis.

In the case of me and my German friend, this could perhaps be achieved by taking a step back and allowing ourselves to ask ourselves the question of what truly is the value of punctuality. About this issue, my friend and I could criticize each other’s views. She might argue that it is important to be punctual because it respects people’s time and shows I do not intend to keep them waiting just for me, whereas I might claim that in an informal situation, I would not want people to feel the need to rush, and thus we should be more lenient when considering at what time to meet for a party.

Weakening our notion of tradition can be done on both a macro and a micro scale. On the macro scale, this would imply reconsidering how we teach people our cultural norms and values. More emphasis needs to be put on learning to criticize one’s own culture, in addition to growing more awareness of other cultural perspectives that are out there. On the micro scale, this would be to practice examining strong positions one holds through a weaker lens and learning to listen to and provide feedback to others who do not share your position.

Philosophical Exercise

Can you think of an example like that of my German friend and I? If so, how could the notion of ‘weak’ thought help you resolve it? Were there any interesting things you learned from that disagreement? If so, how did this encounter help you think about the cultural norms that were previously unchallenged?

References/Further Reading

Caputo, J. D. (2018). A Pelican book: Hermeneutics: Facts and Interpretation in the Age of Information. National Geographic Books.

Gadamer, H., Weinsheimer, J., & Marshall, D. G. (1960). Truth and method. https://academic.oup.com/jaac/article/36/4/487/6338763

Hepburn, R. W., Heidegger, M., Macquarrie, J., & Robinson, E. (1927). Being and time. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB05721088

Hermeneutics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). (2020, December 9). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hermeneutics/

Pariser, D., Vattimo, G., & Snyder, J. R. (1991). The End of Modernity: Nihilism and Hermeneutics in Postmodern culture. Leonardo, 24(5), 625. https://doi.org/10.2307/1575675

Sangiacomo, A. (2023). The Tragedy of the Self: Lectures on Global Hermeneutics. https://doi.org/10.21827/63cfc0e9db70b