Thinking Like a Researcher

5 What makes a good theory?

Theories again

Like we discussed in the previous chapter, a theory is a set of systematically interrelated constructs and propositions intended to explain and predict a phenomenon or behaviour of interest, within certain boundary conditions and assumptions. Since theories are important in business research, it is valuable to discuss theories in some more detail, specifically looking at what makes theories good theories.

Theories as nomothetic explanations

Theories tend to be so-called nomothetic explanations. This means that they seek to explain a class of situations or events rather than one specific situation or event. For example, one reason that students may do poorly on exams is that they may have insufficiently prepared. This is not a ‘law’, but definitely is what we could call an empirical regularity: this idea goes beyond explaining why one particular student did poorly on one particular exam, but explains why many students may do poorly on many different exams. Nomothetic explanations are designed to be generalisable across situations, events, or people.

While understanding theories, it is also important to understand what theories are not. A theory is not data, facts, typologies, taxonomies, or empirical findings. A collection of facts is not a theory, just as a pile of stones is not a house. Likewise, perhaps surprisingly, a collection of constructs (e.g., a typology of constructs) is not a theory. This is because theories must go well beyond constructs to include propositions, explanations, and boundary conditions. Data, facts, and findings operate at the empirical or observational level, while theories operate at the theoretical and conceptual level.

Why theories are useful

There are many benefits to using theories in research. First, theories are very specific about the underlying logic for the occurrence of a phenomenon. Second, they aid in sense-making by helping us synthesise prior empirical findings within a theoretical framework and reconcile contradictory findings by discovering contingent factors influencing the relationship between two constructs in different studies. Third, theories provide guidance for future research by helping identify constructs and relationships that are worthy of further research. Fourth, theories can contribute to cumulative knowledge building by bridging gaps between other theories and by causing existing theories to be re-evaluated in a new light.

Limitations

However, theories also have their own share of limitations. As simplified explanations of reality, theories may not always provide adequate explanations of the phenomenon of interest based on a limited set of constructs and relationships. Theories are designed to be simple and parsimonious explanations, while reality may be significantly more complex. Furthermore, theories may impose blinders or limit researchers’ ‘range of vision’, causing them to miss out on important concepts that are not defined by the theory.

Building blocks of a theory

David Whetten (1989)[1] suggests that there are four building blocks of a good theory: constructs, propositions, logic, and boundary conditions/assumptions. Constructs capture the ‘what’ of theories (i.e., what concepts are important for explaining a phenomenon?), propositions capture the ‘how’ (i.e., how are these concepts related to each other?), logic represents the ‘why’ (i.e., why are these concepts related?), and boundary conditions/assumptions examines the ‘who, when, and where’ (i.e., under what circumstances will these concepts and relationships work?).

In addition to constructs and propositions, which we discussed in the previous chapters, the logic that provides the basis for justifying the propositions as postulated is the third building block of a theory. Logic acts like a ‘glue’ that connects the theoretical constructs and provides meaning and relevance to the relationships between these constructs. Logic also represents the ‘explanation’ that lies at the core of a theory. Without logic, propositions will be ad hoc, arbitrary, and meaningless, and cannot be tied into the cohesive ‘system of propositions’ that is the heart of any theory.

Finally, all theories are constrained by assumptions about values, time, and space, and boundary conditions that govern where the theory can be applied and where it cannot be applied. For example, many economic theories assume that human beings are rational (or boundedly rational) and employ utility maximisation based on cost and benefit expectations as a way of understanding human behaviour. In contrast, political science theories assume that people try to position themselves in their professional or personal environment in a way that maximises their power and control over others. Given the nature of their underlying assumptions, economic and political theories are not directly comparable, and researchers should not use economic theories if their objective is to understand the power structure or its evolution in an organisation. Likewise, theories may have implicit cultural assumptions (e.g., whether they apply to individualistic or collective cultures), temporal assumptions (e.g., whether they apply to early stages or later stages of human behaviour), and spatial assumptions (e.g., whether they apply to certain localities but not to others). If a theory is to be properly used or tested, all of the implicit assumptions that form the boundaries of that theory must be properly understood. Unfortunately, theorists rarely state their implicit assumptions clearly, which leads to frequent misapplications of theories to problem situations in research.

What makes a theory a good theory?

Theories are simplified and often partial explanations of complex social reality. As such, there can be good explanations or poor explanations, and consequently, there can be good theories or poor theories. How can we evaluate the ‘goodness’ of a given theory? Different criteria have been proposed by different researchers, the more important of which are listed below:

1. Logical consistency: Are the theoretical constructs, propositions, boundary conditions, and assumptions logically consistent with each other? If some of these ‘building blocks’ of a theory are inconsistent with each other (e.g., a theory assumes rationality, but some constructs represent non-rational concepts), then the theory is a poor theory.

2. Explanatory power: How much does a given theory explain (or predict) reality? Good theories obviously explain the target phenomenon better than rival theories. For example, if we run a regression analysis, one statistic that we obtain is a so-called R-squared measure. This measure tells us something about how well our model fits our data. This may give us some idea of the explanatory power of our theory.

3. Falsifiability: British philosopher Karl Popper stated in the 1940s that for theories to be valid, they must be falsifiable. Falsifiability ensures that the theory is potentially disprovable, if empirical data does not match with theoretical propositions, which allows for their empirical testing by researchers. In other words, theories cannot be theories unless they can be empirically testable. Tautological statements, such as ‘a day with high temperatures is a hot day’ are not empirically testable because a hot day is defined (and measured) as a day with high temperatures, and hence, such statements cannot be viewed as a theoretical proposition. Falsifiability requires the presence of rival explanations, it ensures that the constructs are adequately measurable, and so forth. However, note that saying that a theory is falsifiable is not the same as saying that a theory should be falsified. If a theory is indeed falsified based on empirical evidence, then it was probably a poor theory to begin with.

4, Parsimony: Parsimony examines how much of a phenomenon is explained with how few variables. The concept is attributed to fourteenth century English logician Father William of Ockham and often called ‘Occam’s razor’. Occam’s razor states that among competing explanations that sufficiently explain the observed evidence, the simplest theory (i.e., one that uses the smallest number of variables or makes the fewest assumptions) is the best. Explanation of a complex social phenomenon can always be increased by adding more and more constructs. However, such an approach defeats the purpose of having a theory, which is intended to be a ‘simplified’ and generalisable explanation of reality. Parsimony relates to the degrees of freedom in a given theory. Parsimonious theories have higher degrees of freedom, which allow them to be more easily generalised to other contexts, settings, and populations.

Approaches to theorising

Knowing how researchers build theories is generally useful, but the strategies discussed below may also help you in your assignment or thesis when thinking about your conceptual model.

So how do researchers build theories? Steinfeld and Fulk (1990)[2] recommend four approaches.

Grounded theory

The first approach is to build theories inductively based on observed patterns of events or behaviours. Such an approach is often called ‘grounded theory building’, because the theory is grounded in empirical observations. This technique is heavily dependent on the observational and interpretive abilities of the researcher, and the resulting theory may be subjective and non-confirmable. Furthermore, observing certain patterns of events will not necessarily make a theory, unless the researcher is able to provide consistent explanations for the observed patterns. This approach is very popular in qualitative research.

Bottom-up

The second approach to theory building is to conduct a bottom-up conceptual analysis to identify different sets of predictors relevant to the phenomenon of interest using a predefined framework. One such framework may be a simple input-process-output framework, where the researcher may look for different categories of inputs, such as individual, organisational, and/or technological factors potentially related to the phenomenon of interest (the output), and describe the underlying processes that link these factors to the target phenomenon. This is also an inductive approach that relies heavily on the inductive abilities of the researcher, and interpretation may be biased by researcher’s prior knowledge of the phenomenon being studied.

Extending or modifying existing theories to related contexts

The third approach to theorising is to extend or modify existing theories to explain a related context, such as by extending theories of individual learning to explain organisational learning. Another example from marketing is theory on customer relationship management. Marketing has seen significant theory building on how to ‘manage’ relationships with customers. Interestingly, initial theorists started their theorizing not from scratch, but built on pre-existing theory on interpersonal relationships, such as between married couples.

While making such an extension, certain concepts, propositions, and/or boundary conditions of the old theory may be retained and others modified to fit the new context. This deductive approach leverages the rich inventory of social science theories developed by prior theoreticians, and is an efficient way of building new theories by expanding on existing ones.

Extending theory by structural similarity

The fourth approach is similar to the third approach, but covers contexts that are not immediately obvious to the untrained eye. A theorist can apply existing theories in entirely new contexts by drawing upon the structural similarities between the two contexts. This approach relies on reasoning by analogy, and is probably the most creative way of theorising using a deductive approach. For instance, Markus (1987)[3] used analogic similarities between a nuclear explosion and uncontrolled growth of networks or network-based businesses to propose a critical mass theory of network growth. Just as a nuclear explosion requires a critical mass of radioactive material to sustain a nuclear explosion, Markus suggested that a network requires a critical mass of users to sustain its growth, and without such critical mass, users may leave the network, causing an eventual demise of the network.

Examples of social science theories

In this section, we present brief overviews of a few illustrative theories from different social science disciplines. These theories explain different types of social behaviors, using a set of constructs, propositions, boundary conditions, assumptions, and underlying logic. You don’t have to know these theories by heart, they just form a (simplistic) introduction to and example of some popular theories. Readers are advised to consult the original sources of these theories for more details and insights on each theory.

Agency theory. Agency theory (also called principal-agent theory), a classic theory in the organisational economics literature, was originally proposed by Ross (1973)[4] to explain two-party relationships—such as those between an employer and its employees, between organisational executives and shareholders, and between buyers and sellers—whose goals are not congruent with each other. The goal of agency theory is to specify optimal contracts and the conditions under which such contracts may help minimise the effect of goal incongruence. The core assumptions of this theory are that human beings are self-interested individuals, boundedly rational, and risk-averse, and the theory can be applied at the individual or organisational level.

The two parties in this theory are the principal and the agent—the principal employs the agent to perform certain tasks on its behalf. While the principal’s goal is quick and effective completion of the assigned task, the agent’s goal may be working at its own pace, avoiding risks, and seeking self-interest—such as personal pay—over corporate interests, hence, the goal incongruence. Compounding the nature of the problem may be information asymmetry problems caused by the principal’s inability to adequately observe the agent’s behaviour or accurately evaluate the agent’s skill sets. Such asymmetry may lead to agency problems where the agent may not put forth the effort needed to get the task done (the moral hazard problem) or may misrepresent its expertise or skills to get the job but not perform as expected (the adverse selection problem). Typical contracts that are behaviour-based, such as a monthly salary, cannot overcome these problems.

Hence, agency theory recommends using outcome-based contracts, such as commissions or a fee payable upon task completion, or mixed contracts that combine behaviour-based and outcome-based incentives. An employee stock option plan is an example of an outcome-based contract, while employee pay is a behaviour-based contract. Agency theory also recommends tools that principals may employ to improve the efficacy of behaviour-based contracts, such as investing in monitoring mechanisms—e.g. hiring supervisors—to counter the information asymmetry caused by moral hazard, designing renewable contracts contingent on the agent’s performance (performance assessment makes the contract partially outcome-based), or by improving the structure of the assigned task to make it more programmable and therefore more observable.

Innovation diffusion theory. Innovation diffusion theory (IDT) is a seminal theory in the communications literature that explains how innovations are adopted within a population of potential adopters. The concept was first studied by French sociologist Gabriel Tarde, but the theory was developed by Everett Rogers in 1962 based on observations of 508 diffusion studies. The four key elements in this theory are: innovation, communication channels, time, and social system. Innovations may include new technologies, new practices, or new ideas, and adopters may be individuals or organisations.

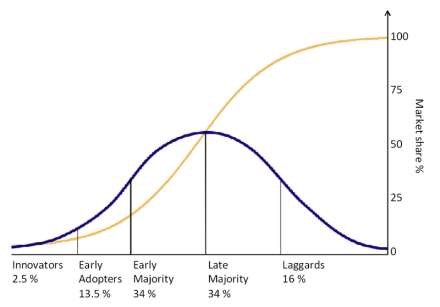

At the macro (population) level, IDT views innovation diffusion as a process of communication where people in a social system learn about a new innovation and its potential benefits through communication channels—such as mass media or prior adopters— and are persuaded to adopt it. Diffusion is a temporal process—the diffusion process starts off slow among a few early adopters, then picks up speed as the innovation is adopted by the mainstream population, and finally slows down as the adopter population reaches saturation. The cumulative adoption pattern is therefore an s-shaped curve, as shown in Figure 6.3, and the adopter distribution represents a normal distribution. All adopters are not identical, and adopters can be classified into innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards based on the time of their adoption. The rate of diffusion also depends on characteristics of the social system such as the presence of opinion leaders (experts whose opinions are valued by others) and change agents (people who influence others’ behaviours).

At the micro (adopter) level, Rogers (1995)[5] suggests that innovation adoption is a process consisting of five stages: one, knowledge: when adopters first learn about an innovation from mass-media or interpersonal channels, two, persuasion: when they are persuaded by prior adopters to try the innovation, three, decision: their decision to accept or reject the innovation, four,: their initial utilisation of the innovation, and five, confirmation: their decision to continue using it to its fullest potential (see Figure 6.4).

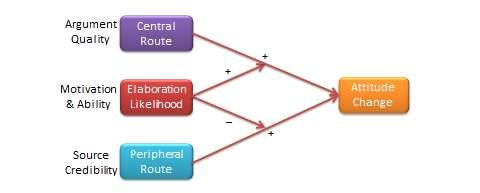

Elaboration likelihood model. Developed by Petty and Cacioppo (1986),[6] the elaboration likelihood model (ELM) is a dual-process theory of attitude formation or change in psychology literature. It explains how individuals can be influenced to change their attitude toward a certain object, event, or behaviour and the relative efficacy of such change strategies. The ELM posits that one’s attitude may be shaped by two ‘routes’ of influence: the central route and the peripheral route, which differ in the amount of thoughtful information processing or ‘elaboration required of people (see Figure 6.5). The central route requires a person to think about issue-related arguments in an informational message and carefully scrutinise the merits and relevance of those arguments, before forming an informed judgment about the target object. In the peripheral route, subjects rely on external ‘cues’ such as number of prior users, endorsements from experts, or likeability of the endorser, rather than on the quality of arguments, in framing their attitude towards the target object. The latter route is less cognitively demanding, and the routes of attitude change are typically operationalised in the ELM using the argument quality and peripheral cues constructs respectively.

Whether people will be influenced by the central or peripheral routes depends upon their ability and motivation to elaborate the central merits of an argument. This ability and motivation to elaborate is called elaboration likelihood. People in a state of high elaboration likelihood (high ability and high motivation) are more likely to thoughtfully process the information presented and are therefore more influenced by argument quality, while those in the low elaboration likelihood state are more motivated by peripheral cues. Elaboration likelihood is a situational characteristic and not a personal trait. For instance, a doctor may employ the central route for diagnosing and treating a medical ailment (by virtue of his or her expertise of the subject), but may rely on peripheral cues from auto mechanics to understand the problems with his car. As such, the theory has widespread implications about how to enact attitude change toward new products or ideas and even social change.

- Whetten, D. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490-495. ↵

- Steinfield, C.W. and Fulk, J. (1990). The theory imperative. In J. Fulk & C.W. (Eds.), Organizations and communications technology (pp. 13–26). Newsburt Park, CA: Sage Publications. ↵

- Markus, M.L. (1987). Toward a ‘critical mass’ theory of interactive media: universal access, interdependence and diffusion. Communication Research, 14(5), 491-511. ↵

- Ross, S.A. (1973). The economic theory of agency: The principal’s problem. American Economic, 63(2), 134-139 ↵

- Rogers, E. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.). New York: Free Press. ↵

- Petty, R.E. and Cacioppo, J.T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag. ↵