Overview of the Scientific Method

7 A Model of Scientific Research in Business

The Business Research Process

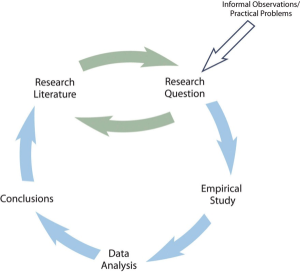

The next few chapters will take you through the actual process of ‘doing’ the research. Figure 8.1 presents a simple model of scientific research in business. Researchers formulate a research question, conduct an empirical study designed to answer the question, analyze the resulting data, draw conclusions, and publish the results so that they become part of the business research literature. This literature is a primary source of new research questions, thus creating a cycle where new research leads to new questions, which lead to further research. Figure 8.1 also illustrates that research questions can originate from informal observations or practical business challenges. Researchers begin by reviewing existing literature to see if the question has already been addressed and refine their question based on prior findings.

Examples of this process

Innovation Management

One study that fits this model well is Ferreira, Coelho, and Moutinho (2021) [1]. Their research question—how strategic alliances influence innovation and new product development—was driven by debate on the mechanism through which strategic alliances affected innovation and new product development.

After reviewing the literature, they propose a specific mechanism which they believe most accurately reflected the underlying process. Next, the authors conduct an empirical study based on a survey, with data collected from managers in Portuguese small and medium enterprises (SME’s). Their analysis shows that strategic alliances indeed do not just directly affect new product development and innovation. Rather, they show strategic alliances work indirectly: strategic alliances first affect so-called exploration and exploitation, which in turn affect innovation and new product development (this is an example of mediation).

The publication of their findings not only contributes to the academic discourse but also leads to many new questions about the specific mechanisms. For example: do these mechanisms always occur? Are there other mechanisms? Is the effect of strategic alliances stronger or weaker depending on context? There’s many more questions you might be able to think of. This research paper is described well by the model above. Prompted by gaps in the literature and practical implications for SMEs, they initiated a study that not only addressed these gaps but also contributed to the academic debate in strategic innovation management. Their work shows the iterative nature of scientific research in business, where practical challenges and academic insights continually lead to new questions and -in time- deeper understanding.

Marketing

Another example of a study fitting this model well is Henderson et al. (2020) [2]. Much literature in marketing has focused on when and why customers switch between different firms, such as energy providers, insurers, retailers, and other types of firms. While much previous work studied factors that cause customers to switch, a recurrent finding in these studies (such as Wieringa & Verhoef (2007)[3]) and in marketing practice is that a surprising number of customers never switch at all, a concept referred to as inertia. Inspired by this observation, Henderson et al. (2020) aimed to better understand the process underlying this inertia: why does it occur, how does it work psychologically, and can firms do anything to break or reinforce such inertia?

The authors conducted a survey and subsequently performed a field experiment in collaboration with a telecommunications service provider. The authors found that there were two processes influencing this inertia, which they refer to as ‘thinking minimization’ and ‘regret minimization’. Subsequently, they find that rewarding customers for their loyalty can, perhaps surprisingly, disrupt inertia based on thinking minimization, but actually reinforce inertia based on regret minimization. By publishing their results, Henderson et al. (2020) contributed to the understanding of customer inertia, and their findings may help firms to tailor marketing strategies in order to reinforce (or, for competitors: disrupt) such inertia.

Again, we see that this study fits the model well: their research is informed by a practical problem (why do many customers stay where they are, despite other firms potentially offering a better deal?), theoretical concerns (not understanding inertia) and prior literature (again, not understanding inertia but seeing that it occurs often). The results of their study have improved our understanding of this process.

- Ferreira, J., Coelho, A., & Moutinho, L. (2021). Strategic alliances, exploration and exploitation and their impact on innovation and new product development: the effect of knowledge sharing. Management Decision, 59(3), 524-567. doi: 10.1108/MD-09-2019-1239 ↵

- Henderson, C. M., Steinhoff, L., Harmeling, C. M., & Palmatier, R. W. (2020). Customer inertia marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49(2), 350-373. doi: 10.1007/s11747-020-00744-0 ↵

- Wieringa, J. E., & Verhoef, P. C. (2007). Understanding Customer Switching Behavior in a Liberalizing Service Market: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Service Research, 10(2), 174-186. doi: 10.1177/1094670507306686 ↵