Overview of the Scientific Method

10 Developing a Hypothesis

Developing Propositions and Hypotheses

Propositions and hypotheses

In a previous chapter, we discussed how you might go about generating new research questions using existing literature on a topic. One you have established a set of variables you are interested in, the next step is to make an ordering in these variables. Often, once you have generated a research question, you will already have a rather good idea on which relationships you want to propose. Take our example on management style effectiveness from a previous chapter for example: once you have established that you’re a) interested in the effectiveness of a certain management style, b) know how you want to define such effectiveness (e.g. employee productivity) and c) have found some characteristic that influences this effectiveness (e.g. manager seniority), your research idea is already very close to a conceptual model with two propositions: this specific management style positively influences employee productivity (1) and the effectiveness of this management style on employee productivity depends on management seniority (2). These propositions can easily be translated to the empirical plane, making them hypotheses.

A hypothesis is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory or proposition is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are usually expressed as statements. For example, for the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable:

H1: There is a positive relationship between a manager’s seniority and employee happiness.

Or for moderation:

H2: The effect of a manager’s seniority on employee happiness is moderated by a manager’s degree of extraversion. For extraverted managers, there is a stronger effect of seniority on employee happiness than for introverted managers.

Or for mediation:

H3: The effect of a manager’s seniority on employee happiness is mediated by their perceived authority.

Deriving propositions and hypotheses from prior theories

But how do researchers derive propositions and hypotheses from prior theories? One approach is to generate a research question using techniques discussed in previous chapters and then ask whether any existing theory implies an answer to this question.

For example, consider the question of how remote work influences employee wellbeing compared to traditional office-based work. Although this question is intriguing on its own, researchers might then investigate whether the job demands-resources (JD-R) theory—the idea that employee health is influenced by the balance between job demands and available resources—implies an answer. If the JD-R theory is correct, remote work might increase employee wellbeing only if employees have sufficient resources (e.g., technology, home office setup) to meet job demands. Another way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on an unexamined component of the theory. For instance, a researcher might concentrate on the specific resources involved in remote work—perhaps hypothesizing that employees with access to high-quality remote working tools show higher wellbeing over time.

Among the most robust hypotheses are those that differentiate between competing theories. For example, consider two theories about how employees’ work environment impacts their creativity. One theory may posit that open-plan offices enhance creativity by facilitating collaboration and spontaneous interactions. Another theory may suggest that open-plan offices hinder creativity due to increased distractions and lack of privacy. To test these theories, researchers might ask employees to complete creative tasks in either an open-plan office or a private office. According to the first theory, employees in open-plan offices should perform better on creative tasks due to the increased opportunity for spontaneous interactions. Conversely, the second theory posits that employees in private offices should perform better because of fewer distractions and more privacy. These theories make opposite predictions, ensuring that only one can be confirmed. If the results show that employees in private offices perform better on creative tasks, this would provide compelling evidence in favor of a distraction-hindrance theory over a collaboration-enhancement theory.

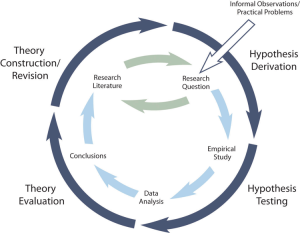

Theory and Hypothesis Testing

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories and hypotheses is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers begin with a set of phenomena and either construct a theory to explain or interpret them or choose an existing theory to work with. They then make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 11.1 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Deci and Ryan’s research on the interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the workplace. They started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. They then constructed their self-determination theory, according to which motivation quality depends on whether an activity is intrinsically or extrinsically motivated. This theory predicts that in some cases (such as monetary rewards), giving extrinsic rewards can undermine individuals’ intrinsic motivation, but in other cases (e.g. positive cases or reinforcement), giving extrinsic rewards might increase intrinsic motivation.

They now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way, but they still needed to test it. They hypothesized that if their theory was correct, they should observe that providing different types of extrinsic rewards should change respondent’s motivation on a specific task aimed at measuring this motivation. To test this hypothesis, Deci conducted a series of experiments with participants engaged in various tasks (Deci, 1971)[1].

In one study, participants were asked to solve puzzles. They received verbal rewards, monetary rewards, or no rewards for each puzzle solved. Deci found that participants who received monetary rewards showed less intrinsic interest in the puzzles when the rewards were removed, compared to those who received no rewards. This result supported the idea that extrinsic rewards can undermine intrinsic motivation for interesting tasks.

Thus, Deci confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for the self-determination theory. This theory has since been widely applied in various business contexts, including employee motivation strategies and performance management systems.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable. We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist.

- Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18(1), 105-115. ↵