7. Rights to Political Participation and Free Elections

Outline of this chapter

This chapter explains how the effective exercise of the rights to political participation and free elections is being undermined by the functioning of AI systems and AI decision-making processes on large online platforms (e.g., social media). More specifically, this chapter addresses:

- the relevant law concerning the right to political participation and the right to free elections (section 7.2)

- the protective scope of the rights and the respective States’ obligations (section 7.3)

- what the new protected interests introduced by recent regulation are and their relationship to human rights law (section 7.4)

- how the concepts of ‘integrity of democratic processes’ and ‘individual’s fair access to and participation in public debate’ under the Framework AI Convention purport to capture some of the new challenges (section 7.5)

- the role of the negative effects on ‘civic discourse’ and ‘electoral processes’ under the DSA to mitigating systemic risks and large-scale societal harms (section 7.6)

(7.1) What’s at Stake? Setting the Scene

Commission opens formal proceedings against TikTok on election risks under the Digital Services Act, 17 December 2024

Today, the Commission has opened formal proceedings against TikTok for a suspected breach of the DSA in relation to TikTok’s obligation to properly assess and mitigate systemic risks linked to election integrity, notably in the context of the recent Romanian presidential elections on 24 November.

[…]

The proceedings will focus on management of risks to elections or civic discourse, linked to the following areas:

-

TikTok’s recommender systems, notably the risks linked to the coordinated inauthentic manipulation or automated exploitation of the service.

-

TikTok’s policies on political advertisements and paid-for political content.

Big Tech companies are increasingly under scrutiny for their influence on elections and, more generally, on political/civic space. The Cambridge Analytica scandal revealed that the data analytics firm that worked with Donald Trump’s election team and the winning Brexit campaign harvested millions of Facebook profiles of US voters and used them to build a software programme to predict and influence choices at the ballot box. It is also documented that TikTok, X and Instagram’s algorithms recommended right-leaning content more than twice as much as left-leaning content to politically interested yet non-partisan users in the 2025 federal elections in Germany.

There are serious concerns on how AI systems of online platforms:

- undue influence voters and their political behaviour, including casting their vote

- compromise individuals’ ability to freely form opinions

- erode the overall environment which gives rise to the formation of political views and political participation

(7.2) Relevant Law

(7.2.1) Right to political participation

Article 25 International Civil and Political Rights

Every citizen shall have the right and the opportunity, without any of the distinctions mentioned in article 2 and without unreasonable restrictions:

1. To take part in the conduct of public affairs, directly or through freely chosen representatives;

2. To vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret ballot, guaranteeing the free expression of the will of the electors;

[…]

(7.2.2) Right to free elections

Article 3, Protocol 1 to the ECHR

The High Contracting Parties undertake to hold free elections at reasonable intervals by secret ballot, under conditions which will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature.

(7.3) Protective Scope of the Right

The scope of the right to political participation (under the ICCPR) and of the right to free elections (under the ECHR) include the guarantee of the conditions which ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people. This guarantee is explicit in the letter of the provisions quoted earlier. However, fleshing out what these conditions are and what the respective States’ obligations are is not challenge-free given the fact that States enjoy a considerable margin of appreciation in this area. The novel risks in the context of AI systems and business practices embedded in very large online platforms and search engines bring to the table societal harms of a large scale and/or with long-term effects in society (e.g., undue influence/manipulation and distortion of the civic space) that are difficult to be identified and isolated under human rights law given the latter’s individualistic character.

For present purposes, the material and discussion focus on the existing “tools” that we have in the human rights law “toolbox” to guarantee the conditions which ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people and aspects of political participation.

(7.3.1) Elections and media pluralism

Human rights bodies emphasise the interrelation between free elections and freedom of expression. Free communication of information and ideas about political issues and a free press able to inform public opinion without censorship or restraint are essential guarantees. States parties to the ECHR have the positive obligation to intervene in order to open up the media to different viewpoints and a diversity of political outlook. However, States enjoy a wide margin of appreciation in the field of electoral legislation.

(7.3.1.1) UN Human Rights Committee, General Comment No 34, Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression, UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/34, 12 September 2011

20. The Committee, in general comment No. 25 on participation in public affairs and the right to vote, elaborated on the importance of freedom of expression for the conduct of public affairs and the effective exercise of the right to vote. The free communication of information and ideas about public and political issues between citizens, candidates and elected representatives is essential. This implies a free press and other media able to comment on public issues and to inform public opinion without censorship or restraint. […]

(7.3.1.2) ECtHR, Manole and Others v. Moldova, App no 13936/02, 17 September 2009

100. […] a duty on the State to ensure that the public has access to impartial and accurate information and a range of opinion and comment, reflecting inter alia the diversity of political outlook within the country […]

(7.3.1.3) ECtHR, Communist Party of Russia and Others v. Russia, App no 29400/05, 19 June 2012

107. […] The interrelation between free elections and freedom of expression was also emphasised in Bowman v. the United Kingdom […], where the Court held that “it is particularly important in the period preceding an election that opinions and information of all kinds are permitted to circulate freely”. Lastly, in Yumak and Sadak v. Turkey [GC], the Court held that the State was under an obligation to adopt positive measures to organise elections “under conditions which will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature”.

[…]

123. […] The next question is whether the State was under any positive obligation under Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 to ensure that media coverage by the State-controlled mass-media was balanced and compatible with the spirit of “free elections” […] In examining this question the Court will bear in mind that “States enjoy a wide margin of appreciation in the field of electoral legislation” […]

[…]

125. […] The Court reiterates that there can be no democracy without pluralism […] In the context of elections the duty of the State to adopt some positive measures to secure pluralism of views has also been recognised by the Court. […]

126. The Court notes that the State was under an obligation to intervene in order to open up the media to different viewpoints. That being said, it is clear that the time and technical facilities available for political broadcast were not unlimited. […]

(7.3.2) Elections and manipulation of the media

ECtHR, Communist Party of Russia and Others v. Russia, App no 29400/05, 19 June 2012

In a rather uncommon case before the ECtHR, the applicants alleged that the media coverage on the TV channels had been predominantly hostile to the opposition parties and candidates due to political manipulation. They further submitted that the biased media coverage had affected public opinion to a critical extent and had made the elections not “free”. The ECtHR found that the applicants’ claims on political manipulation were not substantiated and proved. Interestingly, the Court added that, even if propaganda by a political party takes place, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to determine a causal link between “excessive” political publicity and the election result.

111. In most of the previous cases under Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 the Court has had to consider a specific legislative provision or a known administrative measure which has somehow limited the electoral rights of a group of the population or of a specific candidate. In those cases the measure complained of lay within the legal field, and, therefore, could be easily identified and analysed […]

112. The situation in the present case is different. The applicants did not deny that Russian law guaranteed neutrality of the broadcasting companies, making no distinction between pro-governmental and opposition parties, and proclaimed the principle of editorial independence of the broadcasting companies. They claimed, however, that the law was not complied with in practice, and that de jure neutrality of the five nationwide channels did not exist de facto.

113. The applicant’s position in the present case can be narrowed down to three main factual assertions. First, the applicants alleged that media coverage on the five TV channels had been predominantly hostile to the opposition parties and candidates. Secondly, they asserted that it was a result of a political manipulation, that the executive authorities and/or United Russia had used their influence to impose a policy on the TV companies which had helped to promote United Russia. Thirdly, the applicants claimed that biased media coverage on TV had affected public opinion to a critical extent, and had made the elections not “free”.

114. As to the first point, the Court observes that the Supreme Court in its judgment of 16 December 2004 did not find that the media coverage had been equal in all respects. […] The Supreme Court’s conclusion was formulated more carefully and in a qualified manner: it noted that the tenor of media coverage on TV during the elections had not been so “egregious” to make the ascertaining of the genuine will of the voters impossible.

115. The answer given by the Supreme Court to the applicant’s first point was somewhat elusive. Conversely, on the other two propositions of the applicants the Supreme Court was more explicit. It found in essence that no proof of political manipulation had been adduced, and that no causal link between media coverage and the results of the elections had been shown.

116. The applicants argued that the findings of the Supreme Court in these respects were arbitrary and should not be relied upon. […] The first question is thus whether the Supreme Court’s findings were arbitrary or manifestly unreasonable.

[…]

118. The Supreme Court found that the applicants had failed to show a causal link between the media coverage and the results of the elections. That finding is debatable; it is clear that the media coverage must have at least some effect on the voting preferences. What is true, however, is that the effect of media coverage is often very difficult to quantify. The Court recalls its own finding in the case of Partija Jaunie Demokrāti and Partija Mūsu Zeme v. Latvia where it held that “however important [the propaganda by a political party] may be, [it] is not the only factor which affects the choice of potential voters. Their choice is also affected by other factors […], so it is very difficult, if not impossible, to determine a causal link between “excessive” political publicity and the number of votes obtained by a party or a candidate at issue”. […] the SPS political party which obtained generally positive media coverage did not even pass the minimal electoral threshold. The Rodina political block, by contrast, obtained a much better score at the elections despite poor media coverage. Therefore, the Supreme Court’s arguments in this part did not appear “arbitrary or manifestly unreasonable”.

119. Furthermore, and most importantly, the Supreme Court’s findings did not support the applicants’ allegation of a manipulation of the media by the government, which was their central proposition. The Supreme Court found that the journalists covering elections or political events had been independent in choosing the events and persons to report on, that it had been their right to inform the public about events involving political figures, and that they had not had the intent of campaigning in favour of the ruling party […]

120. The Court notes that, indeed, the applicants did not adduce any direct proof of abuse by the Government of their dominant position in the capital or management of the TV companies concerned. […] [T]he TV journalists in the present case did not complain of undue pressure by the Government or their superiors during the elections. The Court reiterates that the weight to be given to an item of information “is a matter to be assessed, in principle, by the responsible journalists” […], and that the journalists and news editors enjoyed, under Article 10 of the Convention, a wide discretion on how to comment on political matters. The applicants did not sufficiently explain how it was possible, on the basis of the evidence and information available and in the absence of complaints of undue pressure by the journalists themselves, to distinguish between Government-induced propaganda and genuine political journalism and/or routine reporting on the activities of State officials […]

[…]

Alleged failure by the State to comply with its positive obligations

[…]

126. […] As the case shows, the applicants did obtain some measure of access to the nation-wide TV channels; thus, they were provided with free and paid airtime, with no distinction made between the different political forces. The amount of airtime allocated to the opposition candidates was not insignificant. The applicants did not claim that the procedure of distribution of airtime was unfair in any way. Similar provisions regulated access of parties and candidates to regional TV channels and other mass media. In addition, the opposition parties and candidates were able to convey their political message to the electorate through the media they controlled. In this connection, the Court also notes that it follows from the report of the OSCE/ODIHR, which generally found that the main country-wide state sponsored broadcasters that were monitored, openly promoted United Russia, that voters who actively sought information could obtain it from various sources […] The Court considers that the arrangements which existed during the 2003 elections guaranteed the opposition parties and candidates at least minimum visibility on TV.

127. Lastly, the Court turns to the applicants’ allegation that the State should have ensured neutrality of the audio-visual media. […] The question is what sort of interference with journalistic freedom would be appropriate in the circumstances in order to protect the applicants’ rights under Article 3 of Protocol No. 1. […] Having regard to the materials at its possession, including the Supreme Court’s findings […], the Court considers that the applicants’ claims in this respect have not been sufficiently substantiated.

(7.4) New Protected Interests Introduced by Recent Regulation

- What are these new protected interests?

Certain algorithmic harms are not necessarily effectively addressed by human rights law (or other areas of law either). The large scale and systemic nature of said harms cannot be fully captured by human rights law considering the latter’s individualistic character.

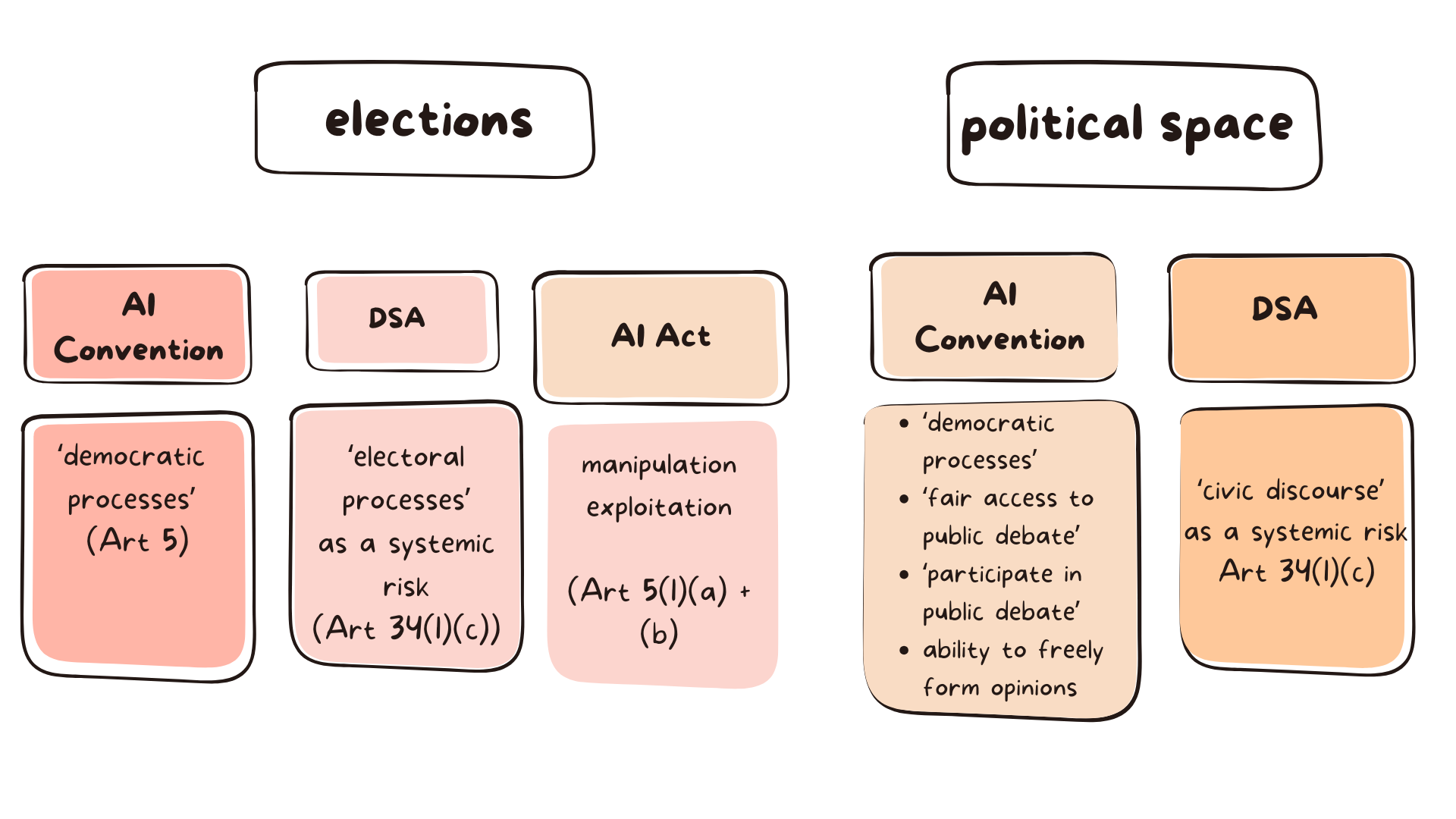

Recent pieces of legislation introduce and protect new regulatory categories/interests, including ‘democratic processes’ and ‘individuals’ fair access to and participation in public debate’, under the Framework AI Convention (7.4.1); or ‘electoral processes’ and ‘civic discourse’, under the DSA (7.4.2). Potential manipulation or exploitation of human vulnerabilities can also be relevant under Article 5(1)(a), (b) EU AI Act (7.4.3) (for prohibited AI practices see discussion in 4.4))

- Distinguishing the recent regulatory developments from human rights law

These interests may seem to be “human rights-like” but they need to be understood in their own context. As far as the Framework AI Convention is concerned, it needs to be reminded that it does not create new rights for individuals or new obligations for States. The Framework AI Convention certainly advances our understanding of the harms at hand and highlights the interconnectedness of interests/rights but it is up to State parties how they will implement the Convention. Turning to the DSA, it does not create rights for individuals; rather, its added value lies in introducing obligations for very large online platforms and search engines on identifying, assessing and mitigating systemic risks. The AI Act does not create rights for individuals either but imposes due diligence and transparency obligations on private and public actors when they develop and/or deploy certain AI systems. Consequently, these new pieces of legislation are underpinned by protecting the at-scale impacts on human rights (among other interests) but strictly speaking they do not qualify as human rights law since they a) do not create rights; b) do not specifically focus on the protection of the individual; and c) do not provide for remedies.

(7.5) ‘Integrity of democratic processes’ and ‘individual’s fair access to and participation in public debate’ under the Framework Convention on AI, Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law

The added value of the Framework AI Convention lies in protecting not only human rights (Article 4) but also democratic processes (Article 5). The Convention stresses:

- state parties’ obligation to adopt measures so that AI systems are not used to undermine the integrity of democratic processes (Article 5(1))

- state parties’ obligation to ensure individuals’ fair access to and participation in public debate (Article 5(2))

- the link between an individual’s ability to freely form opinions and democratic processes (Article 5(2)). Notwithstanding that Article 7 covers states’ obligation to respect individual autonomy, the rationale of Article 5(2) is twofold: first, it pinpoints at the formation of political opinions, as an aspect of individual autonomy; and, second, it stresses the implications of manipulating and altering political opinions on a large scale.

Nonetheless, the Framework AI Convention does not give any further guidance on what these positive obligations of states may be.

(7.5.1) Article 5 – Integrity of democratic processes and respect for the rule of law

1. Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures that seek to ensure that artificial intelligence systems are not used to undermine the integrity, independence and effectiveness of democratic institutions and processes, including the principle of the separation of powers, respect for judicial independence and access to justice.

2. Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures that seek to protect its democratic processes in the context of activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems, including individuals’ fair access to and participation in public debate, as well as their ability to freely form opinions.

42. Artificial intelligence technologies possess significant potential to enhance democratic values, institutions, and processes. Potential impacts include the development of a deeper comprehension of politics among citizens, enabling increased participation in democratic debate or improving the integrity of information in online civic space. […]

[…]

47. Furthermore, the integrity of democracy and its processes is based on two important assumptions referred to in Article 7, namely that individuals have agency (capacity to form an opinion and act on it) as well as influence (capacity to affect decisions made on their behalf). Artificial intelligence technologies can strengthen these abilities but, conversely, can also threaten or undermine them. It is for this reason that paragraph 2 of the provision refers to the need to adopt or maintain measures that seek to protect “the ability [of individuals] to freely form opinions”. With respect to public sector uses of artificial intelligence, this could refer to, for example, general cybersecurity measures against malicious foreign interference in the electoral process or measures to address the spreading of misinformation and disinformation

(7.6) Negative Effects on Civic Discourse and Electoral Processes as Systemic Risks under the DSA

Actual or foreseeable negative effects on electoral processes and civic discourse qualify as systemic risks under Article 34(1)(c) DSA. Providers of very large online platforms and search engines have the obligation to carry out risk assessments and undertake mitigation measures (7.6.1).

As far as electoral processes are concerned, the Commission has published Guidelines with best practices and mitigation measures to be undertaken by providers before, during, and after electoral events (7.6.2). By way of example, the discussion indicates the challenges surrounding real-time election-monitoring tools (7.6.3).

‘Civic discourse’ is a broader notion to ‘electoral processes’ linking elections and political participation. It brings to the foreground the overall environment giving rise to the formation of political views. Curation and moderation practices, the functioning of recommender systems and the visibility of political content are crucial components (7.6.4).

(7.6.1) Risk assessment – Article 34(1)(c) DSA

Providers of very large online platforms and of very large online search engines shall diligently identify, analyse and assess any systemic risks in the Union stemming from the design or functioning of their service and its related systems, including algorithmic systems, or from the use made of their services.

They shall carry out the risk assessments by the date of application referred to in Article 33(6), second subparagraph, and at least once every year thereafter, and in any event prior to deploying functionalities that are likely to have a critical impact on the risks identified pursuant to this Article. This risk assessment shall be specific to their services and proportionate to the systemic risks, taking into consideration their severity and probability, and shall include the following systemic risks:

[…]

any actual or foreseeable negative effects on civic discourse and electoral processes […]

(7.6.2) Mitigation measures to be undertaken before, during, and after electoral events

Commission Guidelines for providers of Very Large Online Platforms and Very Large Online Search Engines on the mitigation of systemic risks for electoral processes pursuant to Article 35(3) of Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, March 2024

22. To reinforce internal processes and resources in a particular electoral context, providers of VLOPs and VLOSEs should consider setting up a dedicated, clearly identifiable internal team prior to each individual electoral period […]. The resource allocation for that team should be proportionate to the risks identified for the election in question, including being staffed by persons with Member State specific expertise, such as local, contextual and language knowledge. The team should cover all relevant expertise including in areas such as content moderation, fact-checking, threat disruption, hybrid threats, cybersecurity, disinformation and FIMI, fundamental rights and public participation and cooperate with relevant external experts […]

27. Specifically, mitigation measures aimed at addressing systemic risks to electoral processes should include measures in the following areas:

[…]

d) Recommender systems can play a significant role in shaping the information landscape and public opinion, as recognised in recitals 70, 84, 88, and 94, as well as Article 34(2) of Regulation (EU) 2022/2065. To mitigate the risk that such systems may pose in relation to electoral processes, providers of VLOPs and VLOSEs should consider:

(i) Ensuring that recommender systems are designed and adjusted in a way that gives users meaningful choices and controls over their feeds, with due regard to media diversity and pluralism;

(ii) Establishing measures to reduce the prominence of disinformation in the context of elections based on clear and transparent methods, e.g. regarding deceptive content that has been fact-checked as false or coming from accounts that have been repeatedly found to spread disinformation;

(iii) Establishing measures to limit the amplification of deceptive, false or misleading content generated by AI in the context of elections through their recommender systems;

(iv) Regularly assessing the performance and impact of recommender systems and addressing any emerging risks or issues related to electoral processes, including by updating and refining policies, practices, and algorithms;

(v) Establishing measures to provide transparency around the design and functioning of recommender systems, in particular in relation to the data and information used in designing systems that foster media pluralism and diversity of content, to facilitate third party scrutiny and research;

(vi) Engaging with external parties to conduct adversarial testing and red team exercises on these systems to identify potential risks such as risks stemming from biases, susceptibility to manipulation, or amplification of misinformation, disinformation, FIMI or other harmful content.

[…]

Fundamental rights

33. Risk mitigation measures, taken in line with Article 35 of Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, should be taken with due regard for the protection of fundamental rights enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, in particular the right to freedom of expression and of information, including media freedom and pluralism. […]

34. When mitigating systemic risks for electoral integrity, the Commission recommends that due regard is also given to the impact of measures to tackle illegal content such as public incitement to violence and hatred to the extent that such illegal content may inhibit or silence voices in the democratic debate, in particular those representing vulnerable groups or minorities. For example, forms of racism, or gendered disinformation and gender-based violence online including in the context of violent extremist or terrorist ideology or FIMI targeting the LGBTIQ+ community can undermine open, democratic dialogue and debate, and further increase social division and polarization. […]

(7.6.3) Case study: Real-time election-monitoring tools

(7.6.3.1) Commission opens formal proceedings against Facebook and Instagram under the Digital Services Act, 30 April 2024

The current proceedings will focus on the following areas:

[…]

The non-availability of an effective third-party real-time civic discourse and election-monitoring tool ahead of the upcoming elections to the European Parliament and other elections in various Member States. Meta is in the process of deprecating “CrowdTangle”, a public insights tool that enables real-time election-monitoring by researchers, journalists and civil society, including through live visual dashboards, without an adequate replacement. However, as reflected in the Commission’s recent Guidelines for providers of Very Large Online Platforms on systemic risks for electoral processes, in times of elections, access to such tools should instead be expanded. The Commission therefore suspects that, taking into account Meta’s deprecation and planned discontinuation of CrowdTangle, Meta has failed to diligently assess and adequately mitigate risks related to Facebook’s and Instagram’s effects on civic discourse and electoral processes and other systemic risks.

(7.6.3.2) Criticism to Meta’s EU election monitoring dashboard

Marsh, ‘Meta’s elections dashboard: A very disappointing sign’, 6 June 2024, AlgorithmWatch

On 3 June, Meta released an EU election monitoring dashboard, responding to investigations by the EU Commission under the Digital Services Act. It is riddled with basic errors, raising severe concerns about Meta’s engagement with risks of electoral interference.

Building election monitoring tools can be complicated. Nonetheless there are basic markers of quality. I used to lead team building dashboards for potential crisis situations in Number 10 Downing Street in the UK. If my team had come up with the product Meta has published, I would have asked them to redo it – because of the issues and missing basic quality standards. It is unclear if Meta would redo their product.

(7.6.4) Case study: Visibility of political content and civic discourse under the DSA

In early 2025, META adopted a new policy regarding its ‘political content approach’, allegedly in an effort to reduce disinformation. The new policy changes how the recommender systems of Instagram and Facebook curate content and, therefore its visibility to users. There is evidence to suggest that the new policy excludes many actors and topics from civic discourse, such as reproductive rights.

(7.6.4.1) META, Our Approach to Political Content, updated 7 January 2025

We want you to have a valuable experience when you use Facebook, Instagram and Threads, which is why we use AI systems to personalise the content you see based on the choices you make. People have told us that they want to see less political content, so we have spent the last few years refining our approach on Facebook to reduce the amount of political content – including from politicians’ accounts – that you see in Feed, Reels, Watch, Groups you should join and Pages you may like. We’ve recently extended this approach in Reels, Explore and in-feed recommendations on Instagram and Threads too.

As part of this, we aim to avoid making recommendations that could be about politics or political issues, in line with our approach of not recommending certain types of content to those who don’t wish to see it.

[….]

(7.6.4.2) Commission opens formal proceedings against Facebook and Instagram under the Digital Services Act, 30 April 2024

Visibility of political content. The Commission suspects that Meta’s policy linked to the ‘political content approach’, that demotes political content in the recommender systems of Instagram and Facebook, including their feeds, is not compliant with DSA obligations. The investigation will focus on the compatibility of this policy with the transparency and user redress obligations, as well as the requirements to assess and mitigate risks to civic discourse and electoral processes.

(7.7) Prohibition of Manipulation and Exploitation of Human Vulnerabilities under the AI Act

Article 5(1)(a) and (b) EU AI Act – Prohibited AI Practices

The following AI practices shall be prohibited:

(a) the placing on the market, the putting into service or the use of an AI system that deploys subliminal techniques beyond a person’s consciousness or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques, with the objective, or the effect of materially distorting the behaviour of a person or a group of persons by appreciably impairing their ability to make an informed decision, thereby causing them to take a decision that they would not have otherwise taken in a manner that causes or is reasonably likely to cause that person, another person or group of persons significant harm;

(b) the placing on the market, the putting into service or the use of an AI system that exploits any of the vulnerabilities of a natural person or a specific group of persons due to their age, disability or a specific social or economic situation, with the objective, or the effect, of materially distorting the behaviour of that person or a person belonging to that group in a manner that causes or is reasonably likely to cause that person or another person significant harm;

For further discussion see section (4.4)

- A Rachovitsa, How AI Systems Threaten to Erode the Rule of Law, Jurist, 13 March 2025

- M Ingram, Threads: You can have political content but you will have to work for it, Columbia Journalism Review, 15 February 2024

- Marsh, ‘Meta’s elections dashboard: A very disappointing sign’, 6 June 2024, AlgorithmWatch

- P Iyer, Report Finds Meta’s Approach to Political Content Reduces Reach for Activist Accounts, Tech Policy Press, 13 August 2024

- S Bradshaw, H Bailey & PN Howard, Report: Industrialized Disinformation: 2020 Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation, Programme on Democracy & Technology, 2021

- J Williams, ‘Ethical Dimensions of Persuasive Technology’, in C Véliz (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Digital Ethics (OUP 2022) 1

On political advertisement:

- Pooja Chaudhuri and Melissa Zhu, ‘What Meta’s Ad Library Shows About Harris and Trump’s Campaigns on Facebook and Instagram’, 4 November 2024 (Bellingcat investigation)

- EU Regulation 2024/900 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 March 2024 on the transparency and targeting of political advertising

Feedback/Errata