4. Right to Freedom of Expression & Thought

Outline of this chapter

This chapter explains how the right to freedom of expression applies to the online environment as well as AI systems. More specifically, this chapter addresses:

- what the protective scope of the right to freedom of expression includes (section 4.1)

- the restrictions that may be imposed on the right of freedom of expression and what the requirements are for said restrictions to be lawful under human rights law (section 4.2)

- how the private governance of content regulation works and how human rights law is relevant (section 4.3)

- whether certain AI systems can be incompatible with the freedom of thought and individual autonomy (section 4.4)

(4.1) Protective Scope of the Right to Freedom of Expression

(4.1.1) Relevant law

Article 10 ECHR European Convention on Human Rights

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This Article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary

Article 19 ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

3. The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

(4.1.2) Clarifying the scope of protection of Article 19 ICCPR

(4.1.2.1) UN Human Rights Committee, General Comment No 34, Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression, UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/34, 12 September 2011

[…]

2. Freedom of opinion and freedom of expression are indispensable conditions for the full development of the person. They are essential for any society. They constitute the foundation stone for every free and democratic society. […]

3. […] The freedoms of opinion and expression form a basis for the full enjoyment of a wide range of other human rights. For instance, freedom of expression is integral to the enjoyment of the rights to freedom of assembly and association, and the exercise of the right to vote.

[…]

11. Paragraph 2 requires States parties to guarantee the right to freedom of expression, including the right to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds regardless of frontiers. This right includes the expression and receipt of communications of every form of idea and opinion capable of transmission to others, subject to the provisions in article 19, paragraph 3, and article 20. It includes political discourse, commentary on one’s own and on public affairs, canvassing, discussion of human rights, journalism, cultural and artistic expression, teaching, and religious discourse. It may also include commercial advertising. The scope of paragraph 2 embraces even expression that may be regarded as deeply offensive, although such expression may be restricted in accordance with the provisions of article 19, paragraph 3 and article 20.

12. Paragraph 2 protects all forms of expression and the means of their dissemination. Such forms include spoken, written and sign language and such non-verbal expression as images and objects of art.23 Means of expression include books, newspapers, pamphlets, posters, banners, dress and legal submissions. They include all forms of audio-visual as well as electronic and internet-based modes of expression.

[…]

15. States parties should take account of the extent to which developments in information and communication technologies, such as internet and mobile based electronic information dissemination systems, have substantially changed communication practices around the world. There is now a global network for exchanging ideas and opinions that does not necessarily rely on the traditional mass media intermediaries. States parties should take all necessary steps to foster the independence of these new media and to ensure access of individuals thereto.

(4.1.3) Protection of Internet-based modes of expression

ECtHR, Times Newspapers Ltd (Nos. 1 and 2) v The United Kingdom, App nos. 3002/03 and 23676/03, 10 March 2009

27. The Court has consistently emphasised that Article 10 guarantees not only the right to impart information but also the right of the public to receive it […]. In the light of [the Internet’s] accessibility and its capacity to store and communicate vast amounts of information, the Internet plays an important role in enhancing the public’s access to news and facilitating the dissemination of information in general.

(4.1.4) Internet access as a human right or as an enabler of exercising freedom of expression?

Community Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Amnesty International & Ors v The Togolese Republic, 25 June 2020

38. Access to internet is not stricto senso a fundamental human right but since internet service provides a platform to enhance the exercise of freedom of expression, it then becomes a derivative right that it is a component to the exercise of the right to freedom of expression. It is a vehicle that provides a platform that will enhance the enjoyment of the right to freedom of expression. Right to internet access is closely linked to the right of freedom of speech which can be seen to encompass freedom of expression as well. Since access to internet is complementary to the enjoyment of the right to freedom of expression, it is necessary that access to internet and the right to freedom of expression be deemed to be an integral part of human right that requires protection by law and makes its violation actionable. In this regard, access to internet being a derivative right and at the same time component part of each other, should be jointly treated as an element of human right to which states are under obligation to provide protection for in accordance with the law just in the same way as the right to freedom of expression is protected.

(4.1.5) States’ obligations and bridging divides

How do we think about the effective exercise of the right to freedom of expression “on the ground”? How different individuals are affected in being able to access the Internet and technological systems or being able to effectively use them?

(4.1.5.1) Global and gender divides

UN Human Rights Council, Res 47/16, The promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet, UN Doc A/HRC/RES/47/16, 7 July 2021

3. Also condemns unequivocally online attacks against women, including sexual and gender-based violence and abuse of women, in particular where women journalists, media workers, public officials or others engaging in public debate are targeted for their expression, and calls for gender-sensitive responses that take into account the particular forms of online discrimination

[…]

8. Calls upon all States to bridge the digital divides, including the gender digital divide, and to enhance the use of information and communications technology, in order to promote the full enjoyment of human rights for all

(4.1.5.2) Participation of persons with disabilities

UN Human Rights Council, Res 38/7, The promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet, UN Doc A/HRC/RES/38/7, 17 July 2018

7. Encourages all States to take appropriate measures to promote, with the participation of persons with disabilities, the design, development, production and distribution of information and communications technology and systems, including assistive and adaptive technologies, that are accessible to persons with disabilities.

(4.2) Restrictions to the Right of Freedom of Expression

A restriction to freedom of expression may be imposed as long as said restriction

a) is provided by law

b) serves one of the legitimate purposes exhaustively enumerated in the respective provision and

c) is necessary in a democratic society.

- Read: Article 19(3) ICCPR and Article 10(2) ECHR

(4.2.1) Conditions to be met for the restrictions to be lawful

UN Human Rights Committee, General Comment No 34, Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression, UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/34, 12 September 2011

21. […] when a State party imposes restrictions on the exercise of freedom of expression, these may not put in jeopardy the right itself. The Committee recalls that the relation between right and restriction and between norm and exception must not be reversed. […]

22. Paragraph 3 lays down specific conditions and it is only subject to these conditions that restrictions may be imposed: the restrictions must be “provided by law”; they may only be imposed for one of the grounds set out in subparagraphs (a) and (b) of paragraph 3; and they must conform to the strict tests of necessity and proportionality. Restrictions are not allowed on grounds not specified in paragraph 3, even if such grounds would justify restrictions to other rights protected in the Covenant. Restrictions must be applied only for those purposes for which they were prescribed and must be directly related to the specific need on which they are predicated.

25. For the purposes of paragraph 3, a norm, to be characterized as a “law”, must be formulated with sufficient precision to enable an individual to regulate his or her conduct accordingly and it must be made accessible to the public. […]

27. It is for the State party to demonstrate the legal basis for any restrictions imposed on freedom of expression. […]

28. The first of the legitimate grounds for restriction listed in paragraph 3 is that of respect for the rights or reputations of others. The term “rights” includes human rights as recognized in the Covenant and more generally in international human rights law. For example, it may be legitimate to restrict freedom of expression in order to protect the right to vote under article 25, as well as rights article under 17 […] Such restrictions must be constructed with care: while it may be permissible to protect voters from forms of expression that constitute intimidation or coercion, such restrictions must not impede political debate, including, for example, calls for the boycotting of a non-compulsory vote. The term “others” relates to other persons individually or as members of a community. Thus, it may, for instance, refer to individual members of a community defined by its religious faith or ethnicity.

29. The second legitimate ground is that of protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

30. Extreme care must be taken by States parties to ensure that treason laws and similar provisions relating to national security, whether described as official secrets or sedition laws or otherwise, are crafted and applied in a manner that conforms to the strict requirements of paragraph 3. […]

31. On the basis of maintenance of public order (ordre public) it may, for instance, be permissible in certain circumstances to regulate speech-making in a particular public place. […]

32. The Committee observed in general comment No. 22, that “the concept of morals derives from many social, philosophical and religious traditions; consequently, limitations… for the purpose of protecting morals must be based on principles not deriving exclusively from a single tradition”. Any such limitations must be understood in the light of universality of human rights and the principle of non-discrimination.

33. Restrictions must be “necessary” for a legitimate purpose. The Committee observed in general comment No. 27 that “restrictive measures must conform to the principle of proportionality; they must be appropriate to achieve their protective function; they must be the least intrusive instrument amongst those which might achieve their protective function; they must be proportionate to the interest to be protected […]

35. When a State party invokes a legitimate ground for restriction of freedom of expression, it must demonstrate in specific and individualized fashion the precise nature of the threat, and the necessity and proportionality of the specific action taken, in particular by establishing a direct and immediate connection between the expression and the threat.

43. Any restrictions on the operation of websites, blogs or any other internet-based, electronic or other such information dissemination system, including systems to support such communication, such as internet service providers or search engines, are only permissible to the extent that they are compatible with paragraph 3. Permissible restrictions generally should be content-specific; generic bans on the operation of certain sites and systems are not compatible with paragraph 3. […]

(4.2.2) States’ obligations when blocking and filtering content online

Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Freedom of expression, states and the private sector in the digital age, UN Doc A/HRC/32/38, 11 May 2016

46. States often block and filter content with the assistance of the private sector. Internet service providers may block access to specific keywords, web pages or entire websites. On platforms that host content, the type of filtering technique depends on the nature of the platform and the content in question. Domain name registrars may refuse to register those that match a government blacklist; social media companies may remove postings or suspend accounts; search engines may take down search results that link to illegal content. The method of restriction required by Governments or employed by companies can raise both necessity and proportionality concerns, depending on the validity of the rationale cited for the removal and the risk of removal of legal or protected expression.

(4.2.3) Assessing whether the individual’s conviction to paying a fine for sharing a link on social media was a necessary restriction to Article 19 ICCPR

Views adopted by the UN Human Rights Committee, Pavel Katorzhevsky v Belarus, communication no. 3095/2018, UN Doc CCPR/C/139/D/3095/2018, 13 October 2023

[…]

7.2 The Committee notes the author’s allegations that the authorities violated his rights under article 19 of the Covenant, as he was convicted and fined for sharing a link on the social media network VKontakte to an article entitled “Idiocy and fake honour to the victims of war in a capital city gymnasium”. […]

[…]

7.4 […] The Committee also notes that when convicting the author, the national courts referred to the decision of the Central District Court of Minsk of 10 November 2016 by which all “informational products” (which include posts to websites and social media platforms) published on vk.com/rdbelarus were declared to be extremist materials and were included in the State List of Extremist Materials.

7.5 […] The Committee observes that, as acknowledged by the State party […], all the informational products (posts) that were published on the mentioned websites before and after the delivery of the court’s decision of 10 November 2016 are automatically declared extremist materials without an individualized assessment of each informational product (post).

7.6 The Committee recalls that any restrictions on the operation of websites, blogs or any other Internet-based, electronic or other such information dissemination systems, including systems to support such communication, such as Internet service providers or search engines, are only permissible to the extent that they are compatible with article 19 (3) of the Covenant. Permissible restrictions generally should be content-specific; generic bans on the operation of certain sites and systems are not compatible with paragraph 3.

7.7 […] The Committee reiterates that even if the sanctions imposed on the author were permitted under domestic law, the State party must show that they were necessary for one of the legitimate aims set out in article 19 (3). The Committee further observes that the State party has failed to invoke any specific grounds related to the author to support the necessity of the restrictions imposed on him, as is required under article 19 (3) of the Covenant.

7.8 In particular, the Committee notes that the court decisions made no individualized assessment of the author’s case and have not provided any explanation as to why the conviction and fine imposed on him were necessary and the least intrusive among the measures which might achieve the relevant protective function and were proportionate to the interest to be protected. It therefore considers that the author’s right to freedom of expression under article 19 (2) of the Covenant has been violated.

(4.2.4) Actio popularis is not allowed in human rights law: conceptualising the victim status requirement under the ECHR in case of collateral effects of a blocking measure

ECtHR, Cengiz and Others v Turkey, App nos. 48226/10 and 14027/11, 1 December 2015

3. Relying on Article 10 of the Convention, the applicants complained in particular of a measure that had deprived them of all access to YouTube.

[…]

5. Mr Cengiz […] is a lecturer at the Law Faculty of İzmir University and is an expert and legal practitioner in the field of freedom of expression. […] Mr Akdeniz is a professor of law at the Law Faculty of Istanbul Bilgi University. Mr Altıparmak is an assistant professor of law at the Political Science Faculty of Ankara University and director of the university’s Human Rights Centre.

The Court’s assessment on the victim status of the applicants

47. The Court notes that in a decision adopted on 5 May 2008, the Ankara Criminal Court of First Instance ordered the blocking of access to YouTube under section 8(1)(b), (2), (3) and (9) of Law no. 5651 on the ground that the content of ten video files available on the website in question had infringed Law no. 5816 prohibiting insults to the memory of Atatürk. The first applicant lodged an objection against the blocking order on 21 May 2010, seeking to have it set aside, and the second and third applicants did likewise on 31 May 2010. In their objections they relied on the protection of their right to freedom to receive and impart information and ideas.

48. On 9 June 2010 the Ankara Criminal Court of First Instance, finding that the applicants had not been parties to the case and thus did not have locus standi to challenge such orders, dismissed their objection. In so doing, it noted, among other things, that the blocking order complied with the requirements of the relevant legislation. It also adopted a further decision on 17 June 2010. Attempts by two of the applicants to challenge that decision were to no avail.

49. The Court reiterates at the outset that the Convention does not allow an actio popularis but requires as a condition for the exercise of the right of individual petition that the applicant be able to claim on arguable grounds that he himself has been a direct or indirect victim of a violation of the Convention resulting from an act or omission which can be attributed to a Contracting State. In Tanrıkulu and Others […], it found that readers of a newspaper whose distribution had been prohibited did not have victim status. Similarly, in Akdeniz […], it held that the mere fact that Mr Akdeniz – like the other users of two music-streaming websites in Turkey – was indirectly affected by a blocking order could not suffice for him to be acknowledged as a “victim” within the meaning of Article 34 of the Convention. In view of those considerations, the answer to the question whether an applicant can claim to be the victim of a measure blocking access to a website will therefore depend on an assessment of the circumstances of each case, in particular the way in which the person concerned uses the website and the potential impact of the measure on him. It is also relevant that the Internet has now become one of the principal means by which individuals exercise their right to freedom to receive and impart information and ideas, providing as it does essential tools for participation in activities and discussions concerning political issues and issues of general interest […]

50. In the present case, the Court observes that the applicants lodged their applications with it as active YouTube users; among other things, they drew attention to the repercussions of the blocking order on their academic work and to the significant features of the website in question. They stated, in particular, that through their YouTube accounts they used the platform not only to access videos relating to their professional sphere, but also in an active manner, for the purpose of uploading and sharing files of that nature. The second and third applicants also pointed out that they had published videos on their academic activities. In that respect, the case more closely resembles that of Mr Yıldırım, who stated that he published his academic work and his views on various topics on his own website […], than that of Mr Akdeniz […], who was acting as a simple website user.

[…]

52. Moreover, as to the importance of Internet sites in the exercise of freedom of expression, the Court reiterates that “[i]n the light of its accessibility and its capacity to store and communicate vast amounts of information, the Internet plays an important role in enhancing the public’s access to news and facilitating the dissemination of information in general” […]. In this connection, the Court observes that YouTube is a video-hosting website on which users can upload, view and share videos and is undoubtedly an important means of exercising the freedom to receive and impart information and ideas. In particular, as the applicants rightly noted, political content ignored by the traditional media is often shared via YouTube, thus fostering the emergence of citizen journalism. From that perspective, the Court accepts that YouTube is a unique platform on account of its characteristics, its accessibility and above all its potential impact, and that no alternatives were available to the applicants.

53. Furthermore, the Court observes that, after the applicants lodged their applications, the Constitutional Court examined whether active users of websites such as https://twitter.com and www.youtube.com could be regarded as victims. In particular, in the case concerning the administrative decision to block access to YouTube, it granted victim status to certain active users of the site, among them the second and third applicants. In reaching that conclusion, it mainly had regard to the fact that the individuals concerned, who all had a YouTube account, made active use of the site. In the case of the two applicants in question, it also took into consideration the fact that they taught at universities, carried out research in the field of human rights, used the website to access a range of visual material and shared their research via their YouTube accounts […] The Court endorses the Constitutional Court’s conclusions concerning these applicants’ victim status. In addition, it observes that the situation of the first applicant, also an active YouTube user, is no different from that of the other two applicants.

54. To sum up, the Court observes that the applicants are essentially complaining of the collateral effects of the measure taken against YouTube in the context of Internet legislation. Their contention is that, on account of the YouTube features, the blocking order deprived them of a significant means of exercising their right to freedom to receive and impart information and ideas.

55. Having regard to the foregoing and to the need for flexible application of the criteria for acknowledging victim status, the Court accepts that, in the particular circumstances of the case, the applicants may legitimately claim that the decision to block access to YouTube affected their right to receive and impart information and ideas even though they were not directly targeted by it. It therefore dismisses the Government’s preliminary objection as to victim status.

(4.2.5) Principle of legality and safeguards regarding the effects of a wholesale blocking of access to a website: foreseeability; transparency of blocking measures; judicial review

ECtHR, Vladimir Kharitonov v Russia, App no 10795/14, 23 June 2020

34. The applicant has been the owner and administrator of a website featuring content relating to the production and distribution of electronic books, from news to analytical reports to practical guides. The website has existed since 2008 and has been updated several times a week. It has been stored on the servers of a US-based company offering accessible shared web-hosting solutions. The applicant’s website has a unique domain name – “www.digital-books.ru” – but shares a numerical network address (“IP address”) with many other websites hosted on the same server.

35. In December 2012, the applicant discovered that access to his website had been blocked. This was an incidental effect of a State agency’s decision to block access to another website which was hosted on the same server and had the same IP address as the applicant’s website. The Court reiterates that measures blocking access to websites are bound to have an influence on the accessibility of the Internet and, accordingly, engage the responsibility of the respondent State under Article 10 […]

36. The applicant was not aware of the proceedings against the third‑party website, the grounds for the blocking measure or its duration. He did not have knowledge of, or control over, when, if ever, the measure would be lifted and access to his website restored. He was unable to share the latest developments and news about electronic publishing, while visitors to his website were prevented from accessing the entire website content. It follows that the blocking measure in question amounted to “interference by a public authority” with the right to receive and impart information, since Article 10 guarantees not only the right to impart information but also the right of the public to receive it […]. Such interference will constitute a breach of Article 10 unless it is “prescribed by law”, pursues one or more of the legitimate aims referred to in Article 10 § 2 and is “necessary in a democratic society” to achieve those aims.

37. The Court reiterates that the expression “prescribed by law” not only refers to a statutory basis in domestic law, but also requires that the law be both adequately accessible and foreseeable, that is, formulated with sufficient precision to enable the individual to foresee the consequences which a given action may entail. […]

38. […] The Court notes with concern that [Russian legislation] allows the authorities to target an entire website without distinguishing between the legal and illegal content it may contain. Reiterating that the wholesale blocking of access to an entire website is an extreme measure which has been compared to banning a newspaper or television station, the Court considers that a legal provision giving an executive agency so broad a discretion carries a risk of content being blocked arbitrarily and excessively.

[…]

41. [Russian legislation] conferred extensive powers on Roskomnadzor in the implementation of a blocking order issued in relation to a specific website. Roskomnadzor can place a website on the Integrated Register of blocked content, ask the website owner and its hosting service provider to take down the illegal content, and add the website’s IP address to the Integrated Register if they refuse to do so or fail to respond. However, the law did not require Roskomnadzor to check whether that address was used by more than one website or to establish the need for blocking by IP address. That manner of proceeding could, and did in the circumstances of the present case, have the practical effect of extending the scope of the blocking order far beyond the illegal content which had been originally targeted […]. In fact, as the applicant and third-party interveners pointed out, millions of websites have remained blocked in Russia for the sole reason that they shared an IP address with some other websites featuring illegal content […]

43. Turning next to the issue of safeguards against abuse which domestic legislation must provide in respect of incidental blocking measures, the Court reiterates that the exercise of powers to interfere with the right to impart information must be clearly circumscribed to minimise the impact of such measures on the accessibility of the Internet. In the instant case, Roskomnadzor gave effect to a decision by which a drug-control agency had determined the content of the offending website to be illegal. Both the original determination and Roskomnadzor’s implementing orders had been made without any advance notification to the parties whose rights and interests were likely to be affected. The blocking measures had not been sanctioned by a court or other independent adjudicatory body providing a forum in which the interested parties could have been heard. Nor did the Russian law call for any impact assessment of the blocking measure prior to its implementation. […]

44. As regards the transparency of blocking measures, the Government submitted that the applicant should have consulted Roskomnadzor’s website. Indeed, Roskomnadzor provides a web service (http://blocklist.rkn.gov.ru/) which enables anyone to find out whether a website has been blocked and indicates the legal basis, the date and number of the blocking decision and the issuing body. It does not, however, give access to the text of the blocking decision, any indication of the reasons for the measure or information about avenues of appeal. Nor does Russian legislation make any provision for third-party notification of blocking decisions in circumstances where they have a collateral effect on the rights of other website owners. […]

45. Lastly, as regards the proceedings which the applicant instituted to challenge the incidental effects of the blocking order, there is no indication that the judges considering his complaint sought to weigh up the various interests at stake, in particular by assessing the need to block access to all websites sharing the same IP address. […] In reaching their decision, the courts confined their scrutiny to establishing that Roskomnadzor had acted in accordance with the letter of the law. However, in the Court’s view, a Convention-compliant review should have taken into consideration […]

46. The Court reiterates that it is incompatible with the rule of law if the legal framework fails to establish safeguards capable of protecting individuals from excessive and arbitrary effects of blocking measures, such as those in issue in the instant case. When exceptional circumstances justify the blocking of illegal content, a State agency making the blocking order must ensure that the measure strictly targets the illegal content and has no arbitrary or excessive effects, irrespective of the manner of its implementation. Any indiscriminate blocking measure which interferes with lawful content or websites as a collateral effect of a measure aimed at illegal content or websites amounts to arbitrary interference with the rights of owners of such websites. […] Accordingly, the interference was not “prescribed by law” and it is not necessary to examine whether the other requirements of paragraph 2 of Article 10 have been met.

(4.2.6) Are generic Internet/services shutdowns lawful under human rights?

UN Human Rights Council, Res 47/16, The promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet, UN Doc A/HRC/RES/47/16, 7 July 2021

11. Condemns unequivocally measures in violation of international human rights law that prevent or disrupt an individual’s ability to seek, receive or impart information online, including Internet shutdowns and online censorship, calls upon all States to refrain from and to cease such measures, and also calls upon States to ensure that all domestic laws, policies and practices are consistent with their international human rights obligations with regard to freedom of opinion and expression, and of association and peaceful assembly, online.

Case study: #KeepItOn: authorities in Mozambique must stop normalizing internet shutdowns during protests, 8 November 2024

We, the undersigned organizations, and members of the #KeepItOn coalition — a global network of over 334 human rights organizations from 105 countries working to end internet shutdowns — urgently demand that the government of Mozambique put an immediate end to the increasing use of shutdowns amid ongoing protests and police crackdown on protesters in Mozambique. Reports from local rights groups indicate that police have resorted to excessive use of violence resulting in more than 20 deaths and multiple injuries.

Since October 25, 2024, in response to growing protests against disputed election results announced by the Election Commission, authorities in Mozambique have imposed at least five instances of curfew style mobile internet shutdowns with the most recent happening on November 6, alongside social media shutdowns lasting several hours. The recent shutdowns in the country follow a worrying trend that authorities in Mozambique began in October 2023, when they imposed a total internet blackout for at least three hours for the first time during local elections. Mozambican authorities’ regular practice of shutting down the internet around elections and in times of political unrest must not be allowed to continue.

Internet shutdowns are a violation of human rights.

[…]

Election-related shutdowns prevent voters, journalists, opposition, and election observers from accessing or sharing essential information, decreasing the fairness, credibility, and transparency of elections. They empower authoritarian regimes to control the narrative throughout the electoral period, undermining the electorate’s ability to make informed decisions, access polling resources, and fully shape their nation’s future. Now more than ever, when there is unrest due to contested election results, the government must ensure people have unfettered access to open and secure internet and digital platforms to promote transparency and access pertinent information in a timely manner.

[…]

Restricting access to the internet, mobile devices, and communication platforms during periods of unrest such as conflicts and protests, and moments of national importance such as elections, further puts people at risk and undermines the enjoyment of all other human rights, from education and work to healthcare and public services, as well as free expression and peaceful assembly […]

Questions to reflect

- How Internet or services shutdowns impact the effective exercise of human rights? Are they lawful under human rights?

- Do you agree with how the ECtHR used the concept of an active YouTube user in the Cengiz and Others v Turkey case to justify the fact that it adopts a flexible application of the criteria for acknowledging victim status while not permitting an action popularis? Who is an active social media user, in your view? Receiving information does not make someone an active social media user?

- What is the meaning of collateral effects and how does the ECtHR use this concept in its reasoning?

- What are measures that States are required to take in order for the collateral effects of a blocking measure of an Internet service/platform to be lawful under Article 10 ECHR?

(4.3) The private governance of content regulation

Content regulation, by platforms and social media form a de facto regime of private censorship. This regime consists of design/engineering choices of technologies embedded in AI systems, policies and terms of service, internal practices as well as moderation and curation practices (section 4.3.1). One of the issues examined here is the conditions upon which states may impose intermediary liability on platforms. The imposition of liability on platforms should not violate the platform’s freedom to impart information under Article 10 ECHR. These were the main issues in the Delfi case before the ECtHR (section 4.3.2). Another issue that we highlight is how terms of service and policies as well as internal remedies set up and enforced by business corporations impact the users’ right to freedom of expression. We discuss this topic from the view of a private “adjudicative” body (MTA Oversight Board) in the “Two buttons” meme case (section 4.3.3). In that case, the Oversight META Board scrutinised Facebook’s policies on satire and Facebook’s content moderators’ capacity to review content containing satire.

(4.3.1) Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Freedom of expression, states and the private sector in the digital age, UN Doc A/HRC/32/38, 11 May 2016

Internal policies and practices

51. Intermediaries’ policies and rules may have significant effects on the freedom of expression. While terms of service are the primary source of regulation, design and engineering choices may also affect the delivery of content.

Terms of service

52. Terms of service, which individuals typically must accept as a condition to access a platform, often contain restrictions on content that may be shared. These restrictions are formulated under local laws and regulations and reflect similar prohibitions, including those against harassment, hate speech, promotion of criminal activity, gratuitous violence and direct threats. Terms of service are frequently formulated in such a general way that it may be difficult to predict with reasonable certainty what kinds of content may be restricted. The inconsistent enforcement of terms of service has also attracted public scrutiny. […] Lack of an appeals process or poor communication by the company about why content was removed or an account deactivated adds to these concerns. […]

Design and engineering choices

55. The manner in which intermediaries curate, categorize and rank content affects what information users access and view on their platforms. For example, platforms deploy algorithmic predictions of user preferences and consequently guide the advertisements individuals might see, how their social media feeds are arranged and the order in which search results appear. Other self-regulatory measures, such as “counter speech” initiatives to support anti-terror or anti-harassment messages, also affect the ways in which users might consume and process Internet content concerning sensitive topics. […]

Remedies

69. To enforce terms of service, companies may not always have sufficient processes to appeal content removal or account deactivation decisions where a user believes the action was in error or the result of abusive flagging campaigns. Further research that examines best practices in how companies communicate terms of service enforcement decisions and how they implement appeals mechanisms may be useful.

71. The appropriate role of the State in supplementing or regulating corporate remedial mechanisms also requires closer analysis. Civil proceedings and other judicial redress are often available to consumers adversely affected by corporate action, but these are often cumbersome and expensive. Meaningful alternatives may include complaint and grievance mechanisms established and run by consumer protection bodies and industry regulators. Several States also mandate internal remedial or grievance mechanisms. […]

(4.3.2) Intermediary liability of platforms and state responsibility under human rights law

ECtHR, Delfi AS v. Estonia, App no 64569/09, 16 June 2015 (Grand Chamber)

Delfi is the first case in which the Court was called upon to examine a complaint regarding user-generated expressive activity and platform liability.

In the this case, the majority of the users’ comments constituted hate speech and/or speech that directly advocated acts of violence. For this reason, the comments did not enjoy the protection of Article 10 ECHR and thus the freedom of expression of the authors of the comments was not an issue in this case.

The question before the Court was whether the domestic courts’ decisions, holding the applicant company liable for these comments posted by third parties, were in breach of the applicant company’s freedom to impart information.

3. The applicant company alleged that its freedom of expression had been violated, in breach of Article 10 of the Convention, by the fact that it had been held liable for the third-party comments posted on its Internet news portal.

11. The applicant company is the owner of Delfi, an Internet news portal that published up to 330 news articles a day at the time of the lodging of the application. Delfi is one of the largest news portals on the Internet in Estonia. It publishes news in Estonian and Russian in Estonia, and also operates in Latvia and Lithuania.

[…]

110. The Court notes at the outset that user-generated expressive activity on the Internet provides an unprecedented platform for the exercise of freedom of expression. That is undisputed and has been recognised by the Court on previous occasions […]. However, alongside these benefits, certain dangers may also arise. Defamatory and other types of clearly unlawful speech, including hate speech and speech inciting violence, can be disseminated like never before, worldwide, in a matter of seconds, and sometimes remain persistently available online. These two conflicting realities lie at the heart of this case. Bearing in mind the need to protect the values underlying the Convention, and considering that the rights under Articles 10 and 8 of the Convention deserve equal respect, a balance must be struck that retains the essence of both rights. Thus, while the Court acknowledges that important benefits can be derived from the Internet in the exercise of freedom of expression, it is also mindful that the possibility of imposing liability for defamatory or other types of unlawful speech must, in principle, be retained, constituting an effective remedy for violations of personality rights.

[…]

117. […] The applicant company’s news portal was one of the biggest Internet media publications in the country; it had a wide readership and there was a known public concern regarding the controversial nature of the comments it attracted […]. Moreover, […] the impugned comments in the present case […] mainly constituted hate speech and speech that directly advocated acts of violence. […]

[…]

Necessary in a democratic society

(a) General principles

131. The fundamental principles concerning the question whether an interference with freedom of expression is “necessary in a democratic society” are well established in the Court’s case-law […]

132. Furthermore, the Court has emphasised the essential function the press fulfils in a democratic society. Although the press must not overstep certain bounds, particularly as regards the reputation and rights of others and the need to prevent the disclosure of confidential information, its duty is nevertheless to impart – in a manner consistent with its obligations and responsibilities – information and ideas on all matters of public interest […].

[…]

136. Moreover, the Court has held that speech that is incompatible with the values proclaimed and guaranteed by the Convention is not protected by Article 10 by virtue of Article 17 of the Convention. The examples of such speech examined by the Court have included statements denying the Holocaust, justifying a pro-Nazi policy, linking all Muslims with a grave act of terrorism, or portraying the Jews as the source of evil in Russia […]

137. The Court further reiterates that the right to protection of reputation is a right which is protected by Article 8 of the Convention as part of the right to respect for private life […].

138. When examining whether there is a need for an interference with freedom of expression in a democratic society in the interests of the “protection of the reputation or rights of others”, the Court may be required to ascertain whether the domestic authorities have struck a fair balance when protecting two values guaranteed by the Convention which may come into conflict with each other in certain cases, namely, on the one hand, freedom of expression protected by Article 10, and, on the other, the right to respect for private life enshrined in Article 8 […]

139. The Court has found that, as a matter of principle, the rights guaranteed under Articles 8 and 10 deserve equal respect, and the outcome of an application should not, in principle, vary according to whether it has been lodged with the Court under Article 10 of the Convention by the publisher of an offending article or under Article 8 of the Convention by the person who was the subject of that article. Accordingly, the margin of appreciation should in principle be the same in both cases […]. Where the balancing exercise between those two rights has been undertaken by the national authorities in conformity with the criteria laid down in the Court’s case-law, the Court would require strong reasons to substitute its view for that of the domestic courts […].

(b) Application of the above principles to the present case

(i) Elements in the assessment of proportionality

140. […] the applicant company removed the comments once it was notified by the injured party, and described them as “infringing” and “illicit” before the Chamber […]. Moreover, the Court is of the view that the majority of the impugned comments amounted to hate speech or incitements to violence and as such did not enjoy the protection of Article 10 […]. Thus, the freedom of expression of the authors of the comments is not in issue in the present case. Rather, the question before the Court is whether the domestic courts’ decisions, holding the applicant company liable for these comments posted by third parties, were in breach of its freedom to impart information as guaranteed by Article 10 of the Convention.

[…]

142. […] In order to resolve the question whether the domestic courts’ decisions holding the applicant company liable for the comments posted by third parties were in breach of its freedom of expression, the [Court] identified the following aspects as relevant for its analysis: the context of the comments, the measures applied by the applicant company in order to prevent or remove defamatory comments, the liability of the actual authors of the comments as an alternative to the applicant company’s liability, and the consequences of the domestic proceedings for the applicant company […]

[…]

(ii) Context of the comments

144. As regards the context of the comments, the Court accepts that the news article about the ferry company, published on the Delfi news portal, was a balanced one, contained no offensive language and gave rise to no arguments regarding unlawful statements in the domestic proceedings. […] Furthermore, it attaches particular weight, in this context, to the nature of the Delfi news portal. It reiterates that Delfi was a professionally managed Internet news portal run on a commercial basis which sought to attract a large number of comments on news articles published by it. […] The applicant company had integrated the comments section into its news portal, inviting visitors to the website to complement the news with their own judgments and opinions (comments). According to the findings of the Supreme Court, in the comments section, the applicant company actively called for comments on the news items appearing on the portal. The number of visits to the applicant company’s portal depended on the number of comments; the revenue earned from advertisements published on the portal, in turn, depended on the number of visits. Thus, the Supreme Court concluded that the applicant company had an economic interest in the posting of comments. In the view of the Supreme Court, the fact that the applicant company was not the author of the comments did not mean that it had no control over the comments section […]

145. The Court also notes in this regard that the Rules on posting comments on the Delfi website stated that the applicant company prohibited the posting of comments that were without substance and/or off topic, were contrary to good practice, contained threats, insults, obscene expressions or vulgarities, or incited hostility, violence or illegal activities. Such comments could be removed and their authors’ ability to post comments could be restricted. Furthermore, the actual authors of the comments could not modify or delete their comments once they were posted on the applicant company’s news portal – only the applicant company had the technical means to do this. In the light of the above […] the applicant company must be considered to have exercised a substantial degree of control over the comments published on its portal.

(iii) Liability of the authors of the comments

147. In connection with the question whether the liability of the actual authors of the comments could serve as a sensible alternative to the liability of the Internet news portal in a case like the present one, the Court is mindful of the interest of Internet users in not disclosing their identity. Anonymity has long been a means of avoiding reprisals or unwanted attention. As such, it is capable of promoting the free flow of ideas and information in an important manner, including, notably, on the Internet. At the same time, the Court does not lose sight of the ease, scope and speed of the dissemination of information on the Internet, and the persistence of the information once disclosed, which may considerably aggravate the effects of unlawful speech on the Internet compared to traditional media. […]

148. The Court observes that different degrees of anonymity are possible on the Internet. An Internet user may be anonymous to the wider public while being identifiable by a service provider […] A service provider may also allow an extensive degree of anonymity for its users, in which case the users are not required to identify themselves at all and they may only be traceable – to a limited extent – through the information retained by Internet access providers.

[…]

(iv) Measures taken by the applicant company

152. The Court notes that the applicant company highlighted the number of comments on each article on its website, and therefore the articles with the most lively exchanges must have been easily identifiable for the editors of the news portal. The article in issue in the present case attracted 185 comments, apparently well above average. The comments in question were removed by the applicant company some six weeks after they were uploaded on the website, upon notification by the injured person’s lawyers to the applicant company […]

153. […] [Given the fact] that the applicant company must be considered to have exercised a substantial degree of control over the comments published on its portal, the Court does not consider that the imposition on the applicant company of an obligation to remove from its website, without delay after publication, comments that amounted to hate speech and incitements to violence, and were thus clearly unlawful on their face, amounted, in principle, to a disproportionate interference with its freedom of expression.

154. The pertinent issue in the present case is whether the national court’s findings that liability was justified, as the applicant company had not removed the comments without delay after publication, were based on relevant and sufficient grounds. With this in mind, account must first be taken of whether the applicant company had put in place mechanisms that were capable of filtering comments amounting to hate speech or speech entailing an incitement to violence.

155. The Court notes that the applicant company took certain measures in this regard. There was a disclaimer on the Delfi news portal stating that the writers of the comments – and not the applicant company – were accountable for them, and that the posting of comments that were contrary to good practice or contained threats, insults, obscene expressions or vulgarities, or incited hostility, violence or illegal activities, was prohibited. Furthermore, the portal had an automatic system of deletion of comments based on stems of certain vulgar words and it had a notice-and-take-down system in place, whereby anyone could notify it of an inappropriate comment by simply clicking on a button designated for that purpose to bring it to the attention of the portal administrators. In addition, on some occasions the administrators removed inappropriate comments on their own initiative.

156. Thus, the Court notes that the applicant company cannot be said to have wholly neglected its duty to avoid causing harm to third parties. Nevertheless, and more importantly, the automatic word-based filter used by the applicant company failed to filter out odious hate speech and speech inciting violence posted by readers and thus limited its ability to expeditiously remove the offending comments. […] The Court notes that as a consequence of this failure of the filtering mechanism these clearly unlawful comments remained online for six weeks […]

157. […] Having regard to the fact that there are ample opportunities for anyone to make his or her voice heard on the Internet, the Court considers that a large news portal’s obligation to take effective measures to limit the dissemination of hate speech and speech inciting violence – the issue in the present case – can by no means be equated to “private censorship”.

[…]

159. […] the applicant company has argued […] that the Court should have due regard to the notice-and-take-down system that it had introduced. If accompanied by effective procedures allowing for rapid response, this system can in the Court’s view function in many cases as an appropriate tool for balancing the rights and interests of all those involved. However, in cases such as the present one, where third-party user comments are in the form of hate speech and direct threats to the physical integrity of individuals, as understood in the Court’s case-law […], the Court considers […] that the rights and interests of others and of society as a whole may entitle Contracting States to impose liability on Internet news portals, without contravening Article 10 of the Convention, if they fail to take measures to remove clearly unlawful comments without delay, even without notice from the alleged victim or from third parties.

[…]

162. Based on the concrete assessment of the above aspects, taking into account the reasoning of the Supreme Court in the present case, in particular the extreme nature of the comments in question, the fact that the comments were posted in reaction to an article published by the applicant company on its professionally managed news portal run on a commercial basis, the insufficiency of the measures taken by the applicant company to remove without delay after publication comments amounting to hate speech and speech inciting violence and to ensure a realistic prospect of the authors of such comments being held liable, and the moderate sanction imposed on the applicant company, the Court finds that the domestic courts’ imposition of liability on the applicant company was based on relevant and sufficient grounds, having regard to the margin of appreciation afforded to the respondent State. Therefore, the measure did not constitute a disproportionate restriction on the applicant company’s right to freedom of expression.

Accordingly, there has been no violation of Article 10 of the Convention.

(4.3.3) How terms of service and remedies by business corporations impact the right to freedom of expression: the view from a private “adjudicative” body (META Oversight Board)

META Oversight Board: “Two buttons” meme case, case no: 021-005-FB-UA, 20 May 2021

2. Case description

On December 24, 2020, a Facebook user in the United States posted a comment with an adaption of the “daily struggle” or “two buttons” meme. A meme is a piece of media, which is often humorous, that spreads quickly across the internet. This featured the same-split screen cartoon from the original meme, but with the Turkish flag substituted for the cartoon character’s face. The cartoon character has its right hand on its head and appears to be sweating. Above the character, in the other half of the split-screen, there are two red buttons with corresponding statements in English: “The Armenian Genocide is a lie” and “The Armenians were terrorists that deserved it.” The meme was preceded by a “thinking face” emoji.

The comment was shared on a public Facebook page that describes itself as forum for discussing religious matters from a secular perspective. It responded to a post containing an image of a person wearing a niqab with overlay text in English: “Not all prisoners are behind bars.” At the time the comment was removed, that original post it responded to had 260 views, 423 reactions and 149 comments. A Facebook user in Sri Lanka reported the comment for violating the Hate Speech Community Standard.

Facebook removed the meme on December 24, 2020. Within a short period of time, two content moderators reviewed the comment against the company’s policies and reached different conclusions. While the first concluded that the meme violated Facebook’s Hate Speech policy, the second determined that the meme violated the Cruel and Insensitive policy. The content was removed and logged in Facebook’s systems based on the second review. On this basis, Facebook notified the user that their comment “goes against our Community Standard on cruel insensitive content.”

After the user’s appeal, Facebook upheld its decision but found that the content should have been removed under its Hate Speech policy. For Facebook, the statement “The Armenians were terrorists that deserved it” specifically violated the prohibition on content claiming that all members of a protected characteristic are criminals, including terrorists. No other parts of the content, such as the claim that the Armenian genocide was a lie, were deemed to be violating. Facebook did not inform the user that it upheld the decision to remove their content under a different Community Standard.

The user submitted their appeal to the Oversight Board on December 24, 2020.

Lastly, in this decision, the Board referred to the atrocities committed against the Armenian people from 1915 onwards as genocide, as this term is commonly used to describe the massacres and mass deportations suffered by Armenians and it is also referred to in the content under review. The Board does not have the authority to legally qualify such atrocities and this qualification is not the subject of this decision.

[…]

4. Relevant standards

The Oversight Board considered the following standards in its decision:

Facebook’s Community Standards

Facebook’s Community Standards define hate speech as “a direct attack on people based on what we call protected characteristics – race, ethnicity, national origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, caste, sex, gender, gender identity, and serious disease or disability.” Under “Tier 1,” prohibited content (“do not post”) includes content targeting a person or group of people on the basis of a protected characteristic with:

- “dehumanizing speech or imagery in the form of comparisons, generalizations, or unqualified behavioral statements (in written or visual form) to or about […] criminals (including, but not limited to, “thieves”, “bank robbers”, or saying “All [protected characteristic or quasi-protected characteristic] are ‘criminals’”).”

- speech “[m]ocking the concept, events or victims of hate crimes even if no real person is depicted in an image.”

- speech “[d]enying or distorting information about the Holocaust.”

However, Facebook allows “content that includes someone else’s hate speech to condemn it or raise awareness.” According to the Hate Speech Community Standard’s policy rationale, “speech that might otherwise violate our standards can be used self-referentially or in an empowering way. Our policies are designed to allow room for these types of speech, but we require people to clearly indicate their intent. If intention is unclear, we may remove content.”

[…]

Human rights standards

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011, establish a voluntary framework for the human rights responsibilities of private businesses. In 2021, Facebook announced its Corporate Human Rights Policy, where it committed to respecting rights in accordance with the UNGPs. The Board’s analysis in this case was informed by the following human rights standards:

- Freedom of expression […]

- The right to non-discrimination […]

- The right to be informed in the context of access to justice […]

User statement

The user stated in their appeal to the Board that “historical events should not be censored.” They noted that their comment was not meant to offend but to point out “the irony of a particular historical event.” The user noted that “perhaps Facebook misinterpreted this as an attack.” […] The user found Facebook and its policies overly restrictive and argued that “[h]umor like many things is subjective and something offensive to one person may be funny to another.”

[…]

8.1.3 Analysis of the combined statements in the meme

The Board is of the view that one should evaluate the content as a whole, including the effect of juxtaposing these statements in a well-known meme. A common purpose of the “daily struggle” or “two buttons” meme is to contrast two different options to highlight potential contradictions or other connotations, rather than to indicate support for the options presented.

For the majority, the exception to the Hate Speech policy is crucial. This exception allows people to “share content that includes someone else’s hate speech to condemn it or raise awareness.” It also states: “our policies are designed to allow room for these types of speech, but we require people to clearly indicate their intent. If intention is unclear, we may remove content.” The majority noted that the content could also fall under the company’s satire exception, which is not publicly available.

Assessing the content as a whole, the majority found that the user’s intent was clear. They shared the meme as satire to raise awareness about and condemn the Turkish government’s efforts to deny the Armenian genocide while, at the same time, justifying the same historic atrocities. The user’s intent was not to mock the victims of these events, nor to claim those victims were criminals or that the atrocity was justified. The majority took into account the Turkish government’s position on genocide suffered by Armenians from 1915 onwards […] as well as the history between Turkey and Armenia. In this context, they found that the cartoon character’s sweating face replaced with a Turkish flag and the content’s direct link to the Armenian genocide, meant the user shared the meme to criticize the Turkish government’s position on this issue. The use of the “thinking face” emoji, which is commonly used sarcastically, alongside the meme, supports this conclusion. […] It would thus be wrong to remove this comment in the name of protecting Armenians, when the post is a criticism of the Turkish government, in support of Armenians.

As such, the majority found that, taken as a whole, the content fell within the policy exception in Facebook’s Hate Speech Community Standard. For the minority, in the absence of specific context, the user’s intent was not sufficiently clear to conclude that the content was shared as satire criticizing the Turkish government. Additionally, the minority found that the user was not able to properly articulate what the alleged humor intended to express. Given the content includes a harmful generalization against Armenians, the minority found that it violated the Hate Speech Community Standard.

[…]

8.3 Compliance with Facebook’s human rights responsibilities

Freedom of expression (Article 19 ICCPR)

Article 19, para. 2 of the ICCPR provides broad protection for expression of “all kinds,” including written and non-verbal “political discourse,” as well as “cultural and artistic expression.” The UN Human Rights Committee has made clear the protection of Article 19 extends to expression that may be considered “deeply offensive” […]

In this case, the Board found that the cartoon, in the form of a satirical meme, took a position on a political issue: the Turkish government’s stance on the Armenian genocide. The Board noted that “cartoons that clarify political positions” and “memes that mock public figures” may be considered forms of artistic expression protected under international human rights law […] […]

While the right to freedom of expression is fundamental, it is not absolute. It may be restricted, but restrictions should meet the requirements of legality, legitimate aim, and necessity and proportionality […]. Facebook should seek to align its content moderation policies on hate speech with these principles […]

Legality

Any rules restricting expression must be clear, precise, and publicly accessible […].Facebook’s Community Standards “permit content that includes someone else’s hate speech to condemn it or raise awareness,” but ask users to “clearly indicate their intent.” In addition, the Board also noted that Facebook removed an exception for humor from its Hate Speech policy following a Civil Rights Audit concluded in July 2020. While this exception was removed, the company kept a narrower exception for satire that is currently not communicated to users in its Hate Speech Community Standard.

The Board also noted that Facebook wrongfully reported to the user that they violated the Cruel and Insensitive Community Standard, when Facebook based its enforcement on the Hate Speech policy. The Board found that it is not clear enough to users that the Cruel and Insensitive Community Standard only applies to content that depicts or names victims of harm.

Additionally, the Board found that properly notifying users of the reasons for enforcement action against them would help users follow Facebook’s rules. This relates to the legality issue, as the lack of relevant information for users subject to content removal “creates an environment of secretive norms, inconsistent with the standards of clarity, specificity and predictability” which may interfere with “the individual’s ability to challenge content actions or follow up on content-related complaints.” […] Facebook’s approach to user notice in this case therefore failed the legality test.

Legitimate aim

Any restriction on freedom of expression should also pursue a “legitimate aim.” The Board agreed the restriction pursued the legitimate aim of protecting the rights of others […]

Necessity and proportionality

[…]

A majority of the Board concluded that Facebook’s interference with the user’s freedom of expression was mistaken. The removal of the comment would not protect the rights of Armenians to equality and non-discrimination. The user was not endorsing the statements contrasted in the meme, but rather attributing them to the Turkish government. They did this to condemn and raise awareness of the government’s contradictory and self-serving position. The majority found that the effects of satire, such as this meme, would be lessened if people had to explicitly declare their intent. The fact that the “two buttons” or “daily struggle” meme is usually intended to be humorous, even though the subject matter here was serious, also contributed to the majority’s decision.

[…]

the Board was concerned with Facebook content moderators’ capacity to review this meme and similar pieces of content containing satire. Contractors should follow adequate procedures and be provided with time, resources and support to assess satirical content and relevant context properly.

While supporting majority’s views on protecting satire on the platform, the minority did not believe that the content was satire. The minority found that the user could be embracing the statements contained in the meme, and thus engaging in discrimination against Armenians. Therefore, the minority held that the requirements of necessity and proportionality have been met in this case. […] The minority found that, similarly, where the satirical nature of the content is not obvious, as in this case, the user’s intent should be made explicit. The minority concluded that, while satire is about ambiguity, it should not be ambiguous regarding the target of the attack, i.e., the Turkish government or the Armenian people.

Oversight Board decision

The Oversight Board overturns Facebook’s decision to remove the content and requires the content to be restored.

Policy advisory statement

[…]

Include the satire exception, which is currently not communicated to users, in the public language of the Hate Speech Community Standard.

[…]

Make sure that it has adequate procedures in place to assess satirical content and relevant context properly. This includes providing content moderators with: (i) access to Facebook’s local operation teams to gather relevant cultural and background information; and (ii) sufficient time to consult with Facebook’s local operation teams and to make the assessment. Facebook should ensure that its policies for content moderators incentivize further investigation or escalation where a content moderator is not sure if a meme is satirical or not.

[…]

- Can you explain and assess in what ways content regulation is subject to private governance?

- What are States’ obligations in supplementing or regulating the private sector?

- What are the elements that the Court adopted in the Delfi case for assessing the proportionality of the restriction imposed on the applicant company’s freedom to impart information under Article 10 ECHR?

- What were the measures applied by the applicant company (Delfi) in order to prevent or remove defamatory comments in the Delfi case?

- How does the ECtHR assess the role of the notice-and-take-down system and in what scenarios States may impose liability on Internet news portals, without contravening Article 10 ECHR?

- Do you agree with how the META Oversight Board in the “Two buttons” meme case weighed the interest of satire under the right to freedom of expression vis-à-vis the prohibition of hate speech?

- How do you assess the Oversight Board’s mandate and work in terms of protecting human rights?

- Check the recommendation tracker of META’s recommendations. Does META enforce the Oversight Board’s recommendations?

Fun play: Two Buttons Meme generator

(4.4) Certain AI systems may not be compatible with freedom of thought and individual autonomy

AI systems that engage in practices of manipulation, exploitation of human vulnerabilities or emotion detection/analysis pose unique risks to individual autonomy and human rights. Examples of such AI systems include recommender systems oradvertisements based on targeting techniques optimised to appeal to individuals’ or groups’ vulnerabilities. Sentiment detection refers to systems that can infer a person’s inner emotional state based on physical, physiological or behavioural markers (e.g., facial expressions, vocal tone) and sort them into discrete categories (e.g., angry).

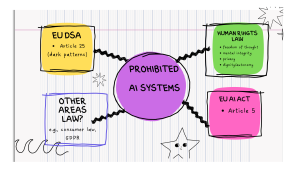

Human rights law has a “toolbox” to unpack these challenges (4.4.2). Different rights may be relevant. The underdeveloped thus far right of freedom of thought has great potential for addressing impermissible interferences with how we form our opinions, process our emotions and make our decisions. The notion of mental integrity or aspects of the right to privacy (mental privacy) may come into play too. Moreover, the principles of human dignity, individual autonomy and self-determination should be brought to the foreground.

At the same time, one should not lose sight of the fact that human rights law may not have the capacity to fully capture and address all novel harms caused by AI systems. Other areas of law may be complementary and relevant, including recent prohibitions of specific AI systems under the EU AI Act, the EU DSA or consumer law (4.4.3).

(4.4.1) Case studies

(4.4.1.1) Sentiment detection: EU’s experimentation with iBorderCtrl and lying-detection

D Boffey, EU border ‘lie detector’ system criticised as pseudoscience, The Guardian, 2 November 2018

The EU has been accused of promoting pseudoscience after announcing plans for a “smart lie-detection system” at its busiest borders to identify illegal migrants. The “lie detector”, to be trialled in Hungary, Greece and Latvia, involves the use of a computer animation of a border guard, personalised to the traveller’s gender, ethnicity and language, asking questions via a webcam.

The “deception detection” system will analyse the micro-expressions of those seeking to enter EU territory to see if they are being truthful about their personal background and intentions. Those arriving at the border will be required to have uploaded pictures of their passport, visa and proof of funds. According to an article published by the European commission, the “unique approach to ‘deception detection’ analyses the micro-expressions of travellers to figure out if the interviewee is lying”.

[…]

The project, which has received €4.5m (£3.95m) in EU funding, has been heavily criticised by experts. Bruno Verschuere, a senior lecturer in forensic psychology at the University of Amsterdam, told the Dutch newspaper De Volskrant he believed the system would deliver unfair outcomes. “Non-verbal signals, such as micro-expressions, really do not say anything about whether someone is lying or not,” he said. “This is the embodiment of everything that can go wrong with lie detection. There is no scientific foundation for the methods that are going to be used now.

.

(4.4.1.2) YouTube and Snapchat recommender systems

Commission sends requests for information to YouTube, Snapchat, and TikTok on recommender systems under the Digital Services Act, 2 October 2024

Today, the Commission has sent a request for information to YouTube, Snapchat, and TikTok under the Digital Services Act (DSA), asking the platforms to provide more information on the design and functioning of their recommender systems. […]

YouTube and Snapchat are requested to provide detailed information on the parameters used by their algorithms to recommend content to users, as well as their role in amplifying certain systemic risks, including those related to the electoral process and civic discourse, users’ mental well-being (e.g. addictive behaviour and content ‘rabbit holes’), and the protection of minors.

(4.4.1.3) Deceptive advertisements and disinformation

Commission opens formal proceedings against Facebook and Instagram under the DSA, Press release, 30 April 2024

The current proceedings will focus on the following areas:

Deceptive advertisements and disinformation. The Commission suspects that Meta does not comply with DSA obligations related to addressing the dissemination of deceptive advertisements, disinformation campaigns and coordinated inauthentic behaviour in the EU. The proliferation of such content may present a risk to civic discourse, electoral processes and fundamental rights, as well as consumer protection.

[…]

(4.4.2) Relevant human rights law

(4.4.2.1) Right to freedom of thought

1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers.

Article 10 EU Charter – Freedom of thought, conscience and religion

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

(4.4.2.1.1) Freedom not to express one’s opinion; coercing the holding or not holding of an opinion

UN Human Rights Committee, General Comment No 34, Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression, UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/34, 12 September 2011

9. Paragraph 1 of article 19 requires protection of the right to hold opinions without interference. This is a right to which the Covenant permits no exception or restriction. Freedom of opinion extends to the right to change an opinion whenever and for whatever reason a person so freely chooses. No person may be subject to the impairment of any rights under the Covenant on the basis of his or her actual, perceived or supposed opinions. All forms of opinion are protected, including opinions of a political, scientific, historic, moral or religious nature. It is incompatible with paragraph 1 to criminalize the holding of an opinion. […]

10. Any form of effort to coerce the holding or not holding of any opinion is prohibited. Freedom to express one’s opinion necessarily includes freedom not to express one’s opinion.

(4.4.2.1.2) Interim report of the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, Ahmed Shaheed, Freedom of thought, UN Doc A/76/380, 5 October 2021