8 Intersubjectivity

General Consensus and the Public Sphere

Jop Hebels

The distinction between objectivity and subjectivity has been paramount in establishing what information can be taken at face-value and what information should be taken, at least more so, with a grain of salt. How this distinction operates and how it can be judged remains a topic of debate. Objectivity and subjectivity refer to the different ways in which we can approach the world and the propositions in it. A proposition in this sense can be understood as an expression of certain states of affairs in the world. A proposition can be true and a proposition can be false, depending on its relation to reality. The dichotomy of objectivity and subjectivity helps clarify this relation of certain propositions to reality. Once this relation is established, it can be decided how much value can be applied to this propositional claim. We can reevaluate our first position to encompass a more nuanced stance, should the situation ask for it. Therefore, objectivity and subjectivity seem to play a crucial role in assessing certain topics or experiences. But what exactly do we mean when we speak of something being either objective or subjective?

Explanation

- Objectivity: A proposition can be considered to have objective truth to it when its truth conditions can be confirmed independently of someone experiencing it. That is to say, that there is no sentient perspective that necessitates a claim being true or not and that the claim is met without the bias of a sentient mind. In other words, as an external view of something, that is nobody’s in particular. It implies a reality outside of ourselves. That the Earth is round and revolves around the Sun is true, even if we never observed it to be true. The word objectivity comes from ‘object’, a thing on itself that exists, even without an observer acknowledging it. Objectivity can be a powerful tool because it most resembles a fact, as something we can believe to be true or false (Baggini & Fosl, 2010).

Example

- A part of something is smaller than the whole of which it is a part.

- Subjectivity: A proposition is subjective if it is dependent on the mind of an observer, a first-person perspective if you will. A claim can be considered true if it is evaluated exclusively from the perspective of the observer. Such a perspective can include biases, emotions, perceptions and opinions that colour an individual experience as something that is uniquely their own. It derives from the word ‘subject’, implying an individual that exercises agency, undergoes conscious experience and is situated in relation to other things that exist outside itself (Solomon, 2005, p. 900).

Example

- Robin and Zennie on a walk, when all of a sudden it starts to rain. Robin enjoys the refreshing rain after a warm day and starts to dance in the pools of water that are forming on the street. Zennie curses the sky for ruining such a beautiful day and begins to sulk. Both are subjective experiences of the phenomenon of rain falling down.

Intersubjectivity

The aim for many scientists has always been to arrive at a notion of objective truth, as something that would have been true, even if we never discovered it to be so, unbound by observation, and thus, completely free from subjective experience. Many thinkers have been sceptical about this interpretation, emphasizing that objective claims will always have been perceived through a subjective beholder, placed within a framework that was designed by these same individual subjects. This has resulted in an overall scepticism with regard to whether complete objective knowledge is even possible. These philosophers would insist that it is more plausible that objective truth is just a set of conclusions, arrived at by a subjective individual, which is shared by many other subjective individuals. In other words, that it is a consensus of subjective experiences that has elevated towards a baseline of what we can consider to be true, and thus has achieved an abstracted notion of objectivity in the process. It is a perception of reality that is shared by multiple individuals, a complicated concept that carries the name of intersubjectivity. Many have defended the view that objectivity is extraordinarily rare, if even possible, and that in most cases what we perceive to be objective, is just intersubjectivity in disguise, the consensus on a subjective claim .

.

Philosopher Thomas Nagel builds on the notion of intersubjectivity by inviting us to consider objectivity and subjectivity not as a static black and white dichotomy, but as a spectrum that encourages an everflowing interplay between individuals and the propositions they hold. In this view, objectivity and subjectivity are not oppositional concepts but points on a continuum, and a combination of both perspectives is made to form our experience and knowledge. At one end of the spectrum there is complete objectivity, hard to obtain but free from all types of experience, existing on its own, and on the other end there is absolute subjectivity, a point of view that is entirely rooted in the individual nature of the subject (Nagel, 1986). Naturally, these ends can be considered quite extreme, but we are free to position ourselves somewhere within the spectrum, depending on what position suits us best. In that way, we do not have to search for truths we may never obtain, and we can also step out of our individual experience a little to find a middle ground that helps us reach a particular goal. Nagel would express the necessity of achieving a successful synthesis between objectivity and subjectivity. The implementation of a strictly objective perspective, in so far this is even possible, can never give a full explanation of human experience. Meanwhile a strictly subjective perspective would be ineffective because it only reaches the domain of one singular individual. We should recognize the inherent limitations on both sides of the dichotomy and find new ways of combining them as one powerful tool in the name of intersubjectivity. We would still have to decide on our place within the spectrum, but this gives us more leeway in deciding a correct strategy for achieving a desired result.

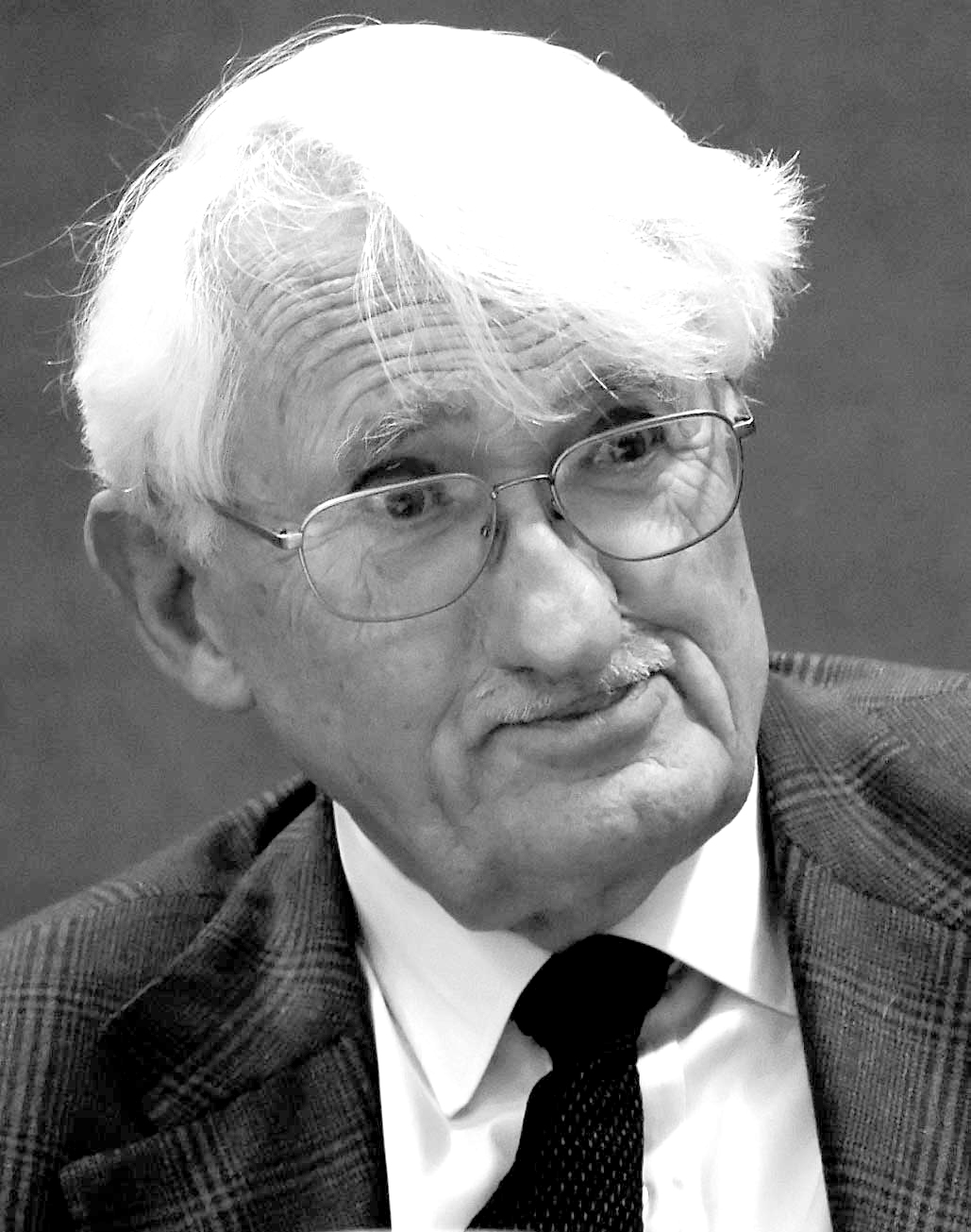

Intersubjectivity in the public sphere

One of the most effective ways to stimulate reaching an intersubjective consensus is by inviting active participation in the public sphere. The public sphere has become a concept that is heavily linked to the works of Jürgen Habermas. By developing a theory that focusses on the operation of the public sphere, Habermas hoped to start a discussion on how we could best arrange public discourse, in which rational and collective decision-making were to be encouraged in such a way that best benefited society. In recognizing the existence and importance of the public sphere, a clear contrast is made with the realm of the private sphere. The private sphere is the domain in which the individual engages in various social roles, thereby forming their subjectivity, consisting of everything that concerns a person on an individual level. These subjective experiences are brought forward in the public sphere, a social space where citizens engage in rational discourse and debate over matters of common concern. In other words, it is the realm where private, subjective individuals discuss matters that are of interest to the collective of these individuals, in a free-flowing discussion, ultimately arriving at a notion of intersubjectivity (Habermas, 1989, pp. 28-34). By introducing the distinction between the private and public sphere, the role of the public sphere was clarified.

According to Habermas, the public sphere was to be essential to the functioning of a democracy because it allowed for citizens, from all layers of society, to express their subjective experiences. Every participant could have equal input in the discussion, as long as their propositions are substantiated by rational thinking. Since everyone is allowed to participate, the public sphere will start to perform on a level of public reasoning that eventually leads to a collective decision-making process that has the common good in mind (Habermas, 1984, p. 42). The communication structure of the public sphere is then connected to private spheres consisting of families, friendships, colleagues, etc. These private spheres are bundled together in the public sphere and, through this intersubjectivity, a consensus is formed, which is then represented in public opinion (Habermas, 1992, p. 361). In this sense, the public sphere represents the forming ground of public reason. As such, it is to become a warning system with its sensors installed all through society, acquiring a signal function for broadly-shared concerns. Because of this function, the forming of accurate public opinion is essential to the public sphere for the level of influence they can assert. But how can it be ensured that accurate public opinion is formed? The answer to this question is called ‘communicative action‘, a form of intersubjectivity in which rationality and mutual understanding reign supreme.

The concept of communicative action is instrumental in how Habermas envisions the public sphere to behave. It implies a form of communication that is heavily linked to what Habermas calls the ‘lifeworld‘. The lifeworld can best be thought of as the background on which our beliefs and norms are founded and from where our lives can be navigated. A background that itself is constructed through intersubjectivity, representing a type of social interaction that is unrestricted by rules, yet follows the values that are accepted throughout society. The interplay between public sphere, communicative action and the lifeworld can be visualized in the form of a circle. The well-being of the lifeworld is essential in allowing individuals to form their own identities and is thus of great importance in realizing communicative action, which in turn is needed for a public sphere to function properly, contributing to sustaining and shaping the lifeworld through the modes of communication that are found in the public sphere. In other words, communicative action enables the well-being of the public sphere, resulting in a healthy lifeworld, influencing our modes of communication again (Habermas, 1987, p. 154-198). Communicative action and the lifeworld stand in direct contrast to strategic action and the system. Strategic action can be recognized by its reliance on instrumental reasoning, always working towards a defined end with a personal gain in mind. If the deliberation of democracy is to be ensured, then strategic action cannot find a place in such a society. The system is herein the direct opposite of the lifeworld, symbolizing everything the lifeworld ought not to be. It is a realm with clearly defined structures and mechanisms that work with a particular goal in mind: to regulate and organize society for their own gain. It is the realm of strategic action, consisting of commercial and political spheres that rely on means-ends calculations.

The lifeworld and the system exist in great tension with one another, leading to Habermas’s greatest fear: the colonization of the lifeworld by the system. In other words, that the strategic action of the system extends into the lifeworld, thereby influencing the autonomy of the public sphere and hindering democratic discourse (Habermas, 1987, pp. 186-196). If we are to prevent the extension of the system into the lifeworld, and thus secure genuine deliberation, then an informal mode of communication in which everyone can participate and in which everyone is held to a standard of rationality and mutual understanding is of the utmost importance. A strong public opinion can then be formed and an intersubjective consensus can eventually be brought forward to the political system and their institutions, a sphere that depends on the public for their power (i.e. elections). Because of this dependence, the political system is ‘forced’ to listen to public opinion and to act in accordance with it. By laying out his theory on the public sphere and communicative rationality, Habermas has given us instructions on how to use our intersubjectivity as a force for action.

Philosophical Exercise #1

- Immerse yourself in the public sphere and have a genuine conversations with three people about climate change. Hear their stories and try to engage with their arguments. This can be within the context of a physical public sphere such as a market square, or in the digital public sphere through the internet.

Intersubjectivity in climate change

Considering Habermas’s theory of the public sphere, it is quite clear to see what sort of role intersubjectivity is to play within the context of climate change. Habermas has made intersubjectivity and rationality central to his conception of communicative action, and therefore intersubjectivity and rationality should be made central to the discussion on climate change. The public sphere should provide the platform in which these debates can occur, where concerned citizens can share their own subjective experiences with climate change and engage in rational and critical discussion. Luckily, this has already been happening. With the age of digitalization came the interconnectedness of everyone around the world, resulting in the biggest public sphere imaginable, giving voice to diverse perspectives. The rise of the internet has made it much easier to share experiences, information and inspiration with our fellow citizens of the world. Consider for example the young climate-change activist Greta Thunberg, who has amassed a large following on social-media platforms, motivating people to take action. With the size of the public sphere nowadays comes a global domain in which individuals can address complex issues such as climate change, a topic of global concern. But if the public sphere can be arranged on such a scale, then why are the opinions about climate change still so divided? Consider again the circle wherein the public sphere, the lifeworld and communicative rationality affect each other’s functioning:

The well-being of the lifeworld is essential in allowing individuals to form their own identities and is thus of great importance in realizing communicative action, which in turn is needed for a public sphere to function properly, contributing to sustaining and shaping the lifeworld through the modes of communication that are found in the public sphere. In other words, communicative action enables the well-being of the public sphere, resulting in a healthy lifeworld, influencing our modes of communication again (Habermas, 1987, p. 154).

If the performance of the public sphere seems to be disappointing, then it would be fair to assume that our modes of communication have been distorted. Rationality and mutual understanding are divorced from public discourse and therefore a general consensus regarding the issue of climate change appears to be missing. Misinformation and corporate interest have spread around the public sphere, creating division and refusing to allow any sense of intersubjectivity to take root. To be more precise, public discourse is being manipulated and strategic action has made its way into the public sphere, delaying necessary actions. To counter this, it is essential that we return to the very basis of communicative action: Keeping an open mind towards our fellow citizens’ perspectives, responding to them with genuine understanding, evaluating their rational reasoning and finding a middle ground from which we can form constructive policies that are broadly shared among the public. A successful example of this communicative approach is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a panel that has made considerable efforts to produce reports that explain the scientific consensus on climate change in ways that are easily accessible to the public. The ways in which they present their findings are organized within the context of communicative action, so they invite an open discussion and engagement with the public, governmental institutions, corporations and climate change experts, and they share interpretations, evidence and perspectives in a transparent manner that results in a more informed discourse within the public sphere. Considering that climate change is one of the bigger challenges we, as a species, have to face, it is not inconceivable that a genuine discussion of such a topic will bring us closer together. Sooner or later we will have to find real solutions to the problem at hand, enhancing public discourse to reach a general consensus based on which concrete actions can be taken. This will enable an open-minded approach to the perspective of other individuals, all in line with the concept of communicative action that Habermas has provided. The TED Talk below further investigates this thought.

Even though Habermas’s notions of communicative action and the public sphere offer a compelling framework through which we can address the complex nature of climate change, it is important to not understate the challenges it faces. For communicative action to work in ways that benefit the discussion, the public sphere must be free from manipulation from the System, allowing people to deliberate in good faith, with the common good in mind. This can be particularly difficult in a world where public discourse is heavily influenced by corporate and political interests, leading to fragmented media coverage or misinformed perspectives with the goal to polarize society. Furthermore, climate change is a long-term and global challenge, while the political policies that affect climate change are usually focused on short-term, local concerns. Bridging this gap requires a sustained effort from the public to engage in constructive and open discourse, encouraging them to make sacrifices in order to tackle the issue of climate change. Institutions should prioritize such a dialogue with the public, educating them on the newest scientific data. In doing so, a discussion that is grounded in facts and rationality is ensured, allowing an intersubjective consensus to take hold. Despite the challenges, there is hope that one day we can achieve such a deliberation. The Paris Agreement represents this approach, as the coming together of nations to negotiate an agreement on the reduction of gas emissions, based on a shared understanding that effective policies need to be made. Even on a more local scale is the implementation of communicative action starting to reap very visible benefits. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has released a report stating that cities that have organized public forums on climate change have seen more involvement in sustainability efforts by their communities (Five Lessons on Community Driven Climate Action, 2024). By emphasizing shared decisionmaking, the individual citizen is made aware that taking action with regard to climate change is not merely a personal choice, but a shared responsibility. These are all very tangible examples of how communicative action could work in reality, and how it can contribute to a better public sphere and a more coherent intersubjective consensus. Once this is established, real policies about climate change can be formulated, leading to a shared responsibility in carrying out those policies.

Philosophical Exercise #2

- Reflect on your own subjectivity about climate change. If someone were to ask your opinion about it, how would you respond? Write this down and try to look at this from different perspectives. How do you feel about your subjectivity about climate change now?

Intersubjectivity in practice

Consider the three short stories below as an example of how intersubjectivity would work. The stories express three different perspectives, experiences or concerns regarding the topic of climate change. All the stories are written in the first-person perspective, to amplify the subjectivity that each perspective brings.

Jurrian, the frustrated farmer

* Beep, beep, beep * The alarm clock is shaking on the nightstand next to me, I can’t even be bothered to turn it off. I have been awake for hours, waiting for that damn thing to make its noise so I can start my day. And besides, who would hear this loud buzzing anyway? They’ve all left for the city. There wasn’t a reason to stay anymore once dad had died. I don’t blame them, I’ve wondered many times myself why I’m still here, but for some reason, I still am.

The soil crunches beneath my boots as I make my rounds. It’s drier than it should be this time of year, but that’s how things are now, I suppose. Dad used to teach us the workings of the seasons, how they could be hard but that we could depend on them. Nowadays, that is over. We would plant after the last frost, water the crops when the earth would get too sturdy and harvest when the first autumn raindrops started to fall down. But that rhythm is gone now. The other day half of my crops were ruined by the storm, and the remaining half barely survived the scorching sun a day later. I’m fighting a losing battle against forces that are out of my reach. Even my neighbours are talking about leaving everything behind and starting a new life in the city, hoping for more security. But when I look around my land, I see years of hard work and memories of entire generations that are tied to this place. These fields raised me, and as long as this land can give me something, anything, I’ll continue to give back to it.

The story of Jurrian is a representation of many people, who have very understandable fears about their way of life going extinct. A profession that has given meaning to generations is now bound in a struggle against nature, a fight it cannot win.

Tines, the city-wanderer

I never thought much about the environment. Growing up, I was surrounded by skyscrapers, traffic-lights and the hum of the city. Nature seemed so far away from me. What can I say, it’s the city, people are mostly concerned with their own lives and their own little problems. We’ll hear about it on the news, but it will never really resonate with us. At most it’s a five-minute topic of conversation we can discuss. I try my best where I can, if it isn’t that much of a bother; I recycle my cans and don’t throw trash on the sidewalks, but at the end of the day I have my own troubles to worry about. Besides, how much can I do anyway?

But then something strange happened yesterday. My friends were going out and they asked if I was coming too. But I didn’t really feel like it, I couldn’t explain it, I just wasn’t in the mood, I suppose. I decided to go for a walk in the park. It’s something that I never do, usually I am way too busy for a walk. I either take the metro, a cab or my bike, whatever gets me to my destination fastest. But now, with nothing to do, I went for a walk in the park. At first I just stuck to the main road, watching joggers go by, seeing people on dates and families with strollers. And then, just on impulse, I decided to take a winding path deeper into the park. The always-present sounds of the city were now muffled in the background, and as I walked, I felt something shift in me.

Ahead of me was a tall oak tree, standing so still, it seemed as if it had all the time in the world. With its branches stretched out, it was supporting all kinds of birds I’d never noticed before. A cacophony of sounds overwhelmed me, as if they were all singing just for me! I felt like an intruder who had stepped into a secret world, just a few steps away from all the noise I was accustomed to. For the first time, I felt connected to something outside myself, as if the whole city and its worries could wait for a while, like I had found a part of myself I hadn’t realized was missing.

As I was making my way home, a bittersweet feeling had taken hold of me. I was now back in the booming city and the noises of the cars were louder than usual, louder than I could handle. All the peace and quiet I had found just moments ago were nothing but a memory now, but what a fond memory it would become. If only I could let these other people, with all their self-centered concerns, experience what I just had, then maybe things would be just a little bit better. But what can a guy like me possibly do?

The story of Tines is about someone who feels disconnected from nature but rethinks his actions once he has established that connection again. Jurrian and Tines could have a conversation about their differing perspectives and lifestyles, discussing possible ways in which they could help each other. Tines could help Jurrian by telling his story, reaffirming the need for climate change policies. And Jurrian could help Tines by showing him that one individual can actually make a difference.

Nell, the climate change scientist

The lab feels colder and more lonely than usual. Whilst scrolling through the data, again, I notice that my heart is not in it. Yesterday’s meeting still weighs heavily on my mind. I’ve spent years researching and studying the latest details, learning every intricacy I could find. But people don’t seem to care; they might nod politely, even ask a question every once in a while, but none of it with the urgency that I am feeling. At the end of the meeting they were all back to discussing their favourite sports team, as if there was nothing we could do anyway.

And this is what hurts me the most, they all talk about climate change as if it’s someone else’s problem. Maybe they expect that someday, someone will wave a magic wand around and all our problems will be solved. How naive. And then there are those people behind their laptops, saying none of it is true, whilst people like me spend their entire lives trying to find solutions. I know it’s not all bad, most people want to help, but they still see climate change as some distant concept that will be taken care of in due time. But for me, it’s right here, right now. It’s as real as the lab equipment in front of me.

I’m tired. Tired of sounding alarms that fall on deaf ears, tired of seeing people mindlessly gazing at me while I show them the data, tired of people changing the subject when I’m talking about hard facts. But I know I cannot stop, all of it would have been for nothing and this is just too important to ignore. Hopefully, tomorrow will be a better day.

Nell resembles the hard-working scientist that cannot get her point across, simply because the public isn’t listening. The issue with Nell is probably that she talks in hard facts too much. Something that is too distant for the general public. But Nell’s story, combined with the story of Jurrian, could really open people’s eyes. The objective, scientific narrative and the subjective experience that we can truly relate to, now this is a story that could grab the attention that is needed for climate change action. That could be a story that could mobilize people like Tines. In just these three short stories, it becomes visible that intersubjectivity could generate a public consensus that could lead to real, tangible action in the context of climate change.

References

Solomon, R. C. (2005). Subjectivity. In Oxford Companion to Philosophy (p. 900). Oxford University Press.

Baggini, J., & Fosl, P. (2010). The Philosopher’s toolkit: A Compendium of Philosophical Concepts and Methods. Chichster, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Nagel, T. (1986). The View from Nowhere. New York: Oxford University Press.

Habermas, J. (1989). In t. b. Burger, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (pp. 28-34). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (1984). The Theory of Communicative Action. In T. b. McCarthy. Boston: Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1992). Between Facts and Norms, chapter 8. In J. Habermas, Between Facts and Norms (pp. 359-366). MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (1987). The Theory of Communicative Action Vol.2. In T. b. McCarthy, The Theory of Communicative Action Vol.2 (pp. 154-198). Boston: Beacon Press.

Five Lessons on Community Driven Climate Action. (2024). Opgehaald van rwjf.org: https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/blog/2024/01/five-lessons-on-community-driven-climate-action.html

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Intersubjectivity-multisensory-engagement-and-empathic-embodiment-in-motion_fig1_373198337

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0743016715300085

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-people-the-state-and-the-public-sphere-Source-van-Krieken-2016_fig1_311771319

https://www.trotta.es/static/img/autores/00002365ztsix.jpg