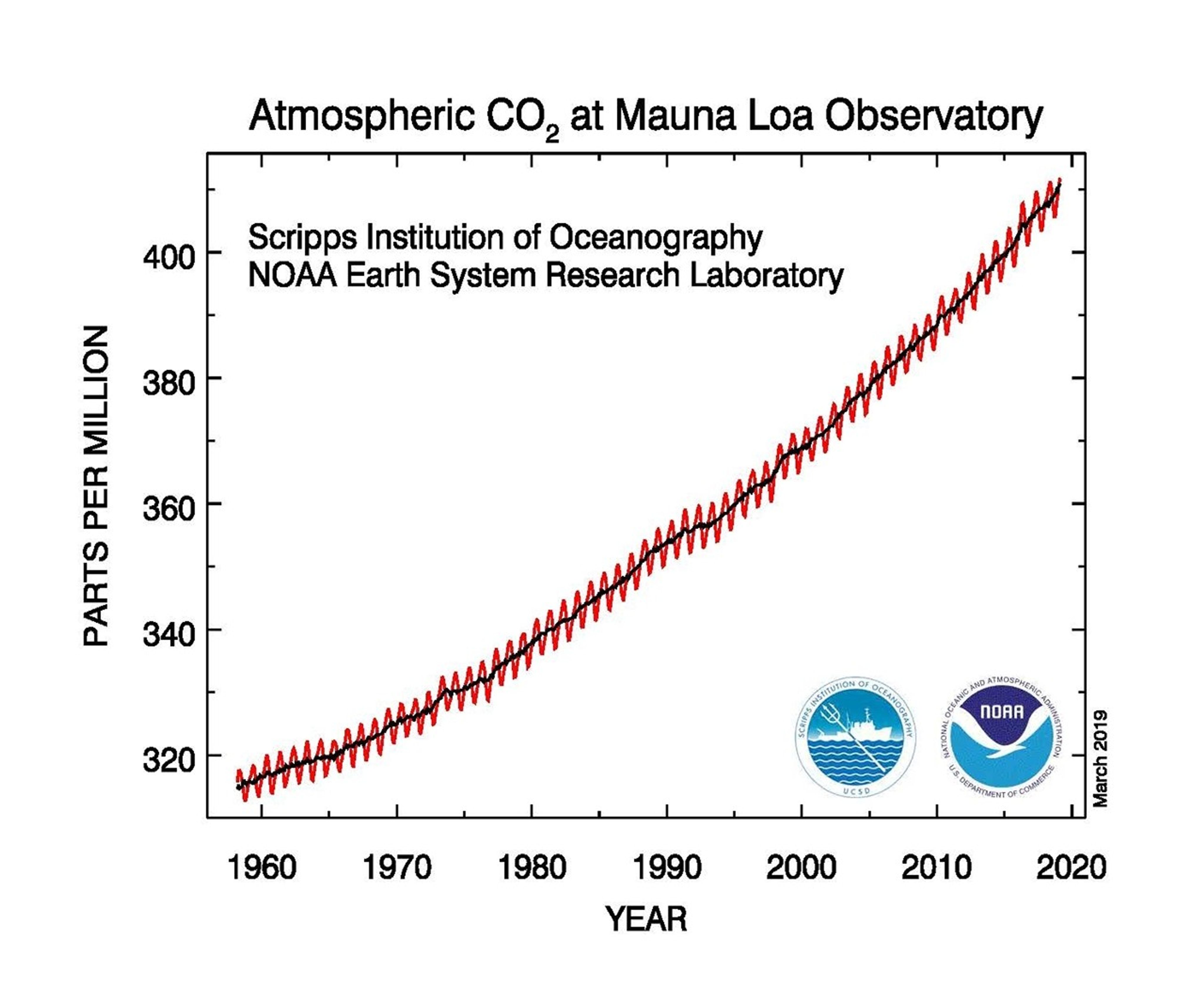

A chart showing the steadily increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (in parts per million) observed at NOAA’s Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii over the course of 60 years. Measurements of the greenhouse gas began in 1959.[7]

15 Longtermism

Daan Baks

Introduction

In the previous chapter on value theory, we explored the complexities of comparing and evaluating values, particularly focusing on when they are complex, diverse or even incommensurable. Value theory explores the nature of what is valuable or what is “good” and helps to understand and evaluate different outcomes when making decisions. Intrinsic and instrumental values are central to this discussion, focusing on those things that are valuable in themselves (e.g., happiness or well-being), versus those things that are valuable for their outcomes (e.g., money or education). As seen in the previous chapter, one can adopt different value theory variants based on the importance of an outcome. However, value theory encounters limitations when we are faced with decisions that carry uncertain outcomes, or when values cannot be directly compared with one another. This is also the case with complex decision-making procedures about choices that impact not only our lives today, but also the future we will pass on. Should we risk investing billions into climate mitigation, despite the certainty of the immediate costs, to protect potential future generations from catastrophic natural disasters? Do we choose short-term gain or possible long-term survival of future generations? These questions highlight the importance of the concept of “longtermism,” which is a framework that emphasizes the ethical importance of bringing about change to positively influence our future generations (also see the chapter on “Bad Faith” by Sartre). It asserts that future people, regardless of when or where they will exist, have an equal moral significance as those who live today.

The story of claire and Max

While the sun was setting on the horizon, Claire was still exploring a forgotten trail in the hills. As she walked, Claire found a beautiful resting spot where she decided to enjoy a sip of water while overlooking a small pond nestled between the rocks.

As she pulled her glass water bottle out of her bag, she suddenly lost her grip, the bottle slipped out of her hand and shattered into a thousand pieces across the trail. Shocked and a bit sad, Claire looked at the sunlight-reflecting glass shards on the ground and asked herself whether to clean it up.

In a hurry because of the setting sun, she brushed off her hands and decided to leave the shattered glass behind. While walking she tried to justify her decision by claiming that since this is a forgotten trail, no one would even walk it and the glass wouldn’t be a problem.

But then all of a sudden, she gets an anonymous video call on her phone. She picks it up and a deep, manly voice starts talking. His name is Max, and he is from the distant future, about 95 years ahead. He called to tell Claire that he just injured his foot because he had walked through the shattered glass, which she left behind a few minutes ago. In his eyes Claire sees his pain and feels guilty for not cleaning up after herself, realizing that her actions impacted someone’s future life.

Expected Value Theory in Philosophy and Ethical Thought

“Expected Value” (EV) theory is an extension of value theory that can help make complex ethical choices. Unlike value theory, EV theory provides a structured quantitative approach to decision-making processes that deal with uncertainties, helping us evaluate actions based on their potential outcomes or consequences. This is particularly relevant for climate change and longtermism because it forces us to decide how much value we place on the lives and well-being of our future generations. But before diving into EV for climate change and future generations, we first take a look at the history of EV theory.

EV theory began initially as a mathematical and economic tool to calculate the anticipated benefit of uncertainties based on their own probabilities. In the simplest form the formula of EV can be as follows:

EV= (Probability) x (Value)

So, the probability of each outcome is multiplied by its assigned value or benefit. If these values are combined, then EV provides a quantifiable estimate of the most rational choice in a situation with an uncertain outcome. At first glance, it might seem odd for philosophers to copy this concept from probability theory. However, in ethical dilemmas, where the lives of people are at stake, EV has become a prominent framework for moral reasoning.

The philosophical roots of EV stretch back to the 17th century when Blaise Pascal proposed an intriguing wager, known as “Pascal’s Wager.”[1] He argued that believing in God, even when the probability of God’s existence is slim, still has positive expected value because the potential reward (eternal life in heaven) vastly outweighs the cost of disbelief. See the table below:

God exists |

God does not exist |

|

You believe |

Infinite gain | No loss |

You do not believe |

Infinite loss | No gain |

While Pascal’s Wager runs into multiple critiques such as “Pascalian fanaticism,” which holds that tiny probabilities of extreme outcomes are given overwhelming importance in decision-making, his wager still introduced a probabilistic way of thinking about the potential impact of human decisions that changed the moral debate. Daniel Bernoulli[2] would later expand upon Pascal’s work by using EV as a way to assess risk and reward, balancing the possibility of loss and the lure of gain.

Today EV theory can help as a framework for complicated ethical concerns that influence the lives of future people. It sits at the heart of longtermism, which prioritizes the lives of people and underpins the importance of their well-being. This line of thinking is proposed by philosophers like Nick Bostrom[3] and Hilary & MacAskill.[4] The decisions made today could influence the course of human civilization for centuries or even millennia, as even the smallest reduction in existential risk might positively impact or even save the lives of millions of future people. Therefore, the reduction of such existential risks, like climate change, should be of high ethical concern to us today. However, it is important to mention that EV theory does not claim to predict the future, nor does it settle the question of what the highest values of life are. Rather, it provides a way to approach decision-making procedures with a plan, by weighing possible outcomes based on their likelihood and desirability.

Philosophical Excercise 1:

Try it yourself!

This first philosophical exercise uses Pascal’s Wager to understand how small probabilities of major outcomes can justify our actions today, in relation to climate issues.

- Frame a decision: Think about a climate-related decision, such as investing in emission reduction. Ask yourself the question whether we should take the risk of short-term costs even if the long-term impact is uncertain.

- Consider small probabilities: The chance of catastrophic climate events may be low; the potential impact could be immense.

- Assign rough values and probabilities: Try to assign rational probabilities to the chosen values, and write these down in Pascal’s Wager table.

- Calculate the Expected Values for each choice: By using the formula: EV= (Probability) x (Value), calculate the EV for each option.

- Reflect on our moral responsibility: See whether the potential benefits justify the immediate costs and reflect on what that outcome means for our moral responsibility.

Longtermism

As stated previously, the perspective of longtermism emphasizes the ethical significance of positively impacting the lives of

future people. Philosopher William MacAskill advocates for this idea in his book What We Owe the Future,[5] where his idea of longtermism relies on four fundamental premises: (1) The lives of future people are of equal moral importance; (2) There are likely vast numbers of future people;

(3) Future people cannot vote on or influence our current decisions nor can they sue us; (4) There are ways to positively impact the distant future. These premises establish the ethical foundation for the application of EV theory to climate action by offering a practical framework for prioritizing decisions that positively influence our future generations.

-

The lives of future people are of equal moral importance

Starting with probably the most uncontroversial premise of the four, future people have the same intrinsic moral value as those alive today regardless of the time that separates us; the well-being, suffering, and opportunities experienced by future individuals are of equal moral significance as our own. By extension, if our actions today can reduce the suffering or improve the well-being of those future people, we hold a moral obligation to do so.

-

There are (probably) vast numbers of future people

MacAskill’s second premise emphasizes the vast amounts of human lives that are still to come in the future. The average mammalian species lives around 1 million years; since humans have only walked this earth for about 200,000 years, there are still 800,000 years to come. Besides that, we humans have proven not to be the average mammalian species, therefore we might extend our civilizations for an even longer period of time. But assuming that we do not extinguish ourselves before, humans should still live for at least another 800,000 years. This is a big, substantial number, and the number of people yet to live could be orders of magnitude larger than those that are alive today—future people with the same moral rights and values as we have, again emphasizing the importance of what is at stake in our choices today.

-

Future people cannot influence the decisions of today

MacAskill’s third premise proposes that future generations cannot advocate for their own interests in our current political and economic systems. They cannot vote, discuss, or sue for the damages or suffering they may experience as a result of our decisions made today. This lack of representation creates a moral obligation of the present generation to act based on future interests. The theory of longtermism thus requires a forward-looking mindset, where EV theory can quantify how choices that we make today could benefit the well-being of those that come after us.

Consider for example policies on carbon emissions. Governments of today might be incentivized to pursue growth over sustainability, as sustainability often involves immediate costs and not necessarily direct benefits. However, EV calculations can help policymakers take into account the burden placed on future generations caused by our actions. Through estimation of both the probability and magnitude of future consequences, EV theory provides a quantitative foundation for advocating climate action on behalf of those who are not able to represent themselves.

-

There are ways to positively impact the long-term future

The final premise rests on the idea that although the future may seem unpredictable, our actions today still have the potential to positively impact the distant future, mainly by focusing on reducing the probability of existential risks. Even minor changes in present-day policies regarding climate mitigation can yield significant long-term effects. Imagine for instance two cruise ships that are both setting sail from London to New York. However, one ship, say Ship2, has a swimmer at the rear of the ship who just barely nudges the ship. That tiny push of the swimmer may seem meaningless at first glance but over a long period and distance, it hugely influences the course of Ship2. Ship1 ends up in New York City while Ship2 ends up all the way in Venezuela. This example illustrates how even the smallest actions we take today, for instance cutting emissions or conserving resources, can have a significant impact on the future, even if that action may feel insignificant in the moment itself.

In the context of climate change, EV theory encourages us to adopt proactive measures by recognizing that even minor reductions in emissions or investments in sustainable practices may reduce the suffering of future people and even reduce existential risks. It is important to adopt this view and take into perspective how we can influence the future of our descendants.

So, longtermism combined with EV calculations, as seen in the cruise ship example, can have a significant impact on the human lives that will (hopefully) follow for at least the next 800,000 years. This approach demands today’s generation to think beyond immediate needs and benefits by recognizing that we have a moral obligation to look out for the well-being of those lives that will follow. Watch the video of MacAskill’s lecture on What We Owe the Future below for further information.

Expected Value Applied to Climate Change

Viewed through the lens of longtermism, climate change is one of humanity’s most prominent existential risks. This is where EV theory can be applied to offer a structured way to assess climate actions based on their potential benefits for the long-term generations to come. Climate change especially poses a significant threat because it creates largely irreversible consequences, such as rising sea levels, extreme weather events, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem degradation. For instance, the carbon dioxide we emit today remains in the atmosphere for 300 up to 1000 years.[6] This means that centuries or even millennia after today the effects of our carbon emissions will still be present in the atmosphere, warming the planet and transforming the ecosystem on Earth far beyond our lifespan. Therefore, climate change is a critical issue to tackle within longtermist ethics, as the welfare of future lives is at stake.

Quotes from: The atmosphere: Getting a handle on carbon dioxide – NASA science

“Carbon dioxide is a different animal, however. Once it’s added to the atmosphere, it hangs around, for a long time: between 300 to 1,000 years. Thus, as humans change the atmosphere by emitting carbon dioxide, those changes will endure on the timescale of many human lives.”

“One could say that because the atmosphere is so thin, the activity of 7.7 billion humans can actually make significant changes to the entire system,” he added. “The composition of Earth’s atmosphere has most certainly been altered. Half of the increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations in the last 300 years has occurred since 1980, and one quarter of it since 2000. Methane concentrations have increased 2.5 times since the start of the Industrial Age, with almost all of that occurring since 1980. So, changes are coming faster, and they’re becoming more significant.”

“Crisp points out that scientists know the increases in carbon dioxide are caused primarily by human activities because carbon produced by burning fossil fuels has a different ratio of heavy-to-light carbon atoms, so it leaves a distinct “fingerprint” that instruments can measure. A relative decline in the amount of heavy carbon-13 isotopes in the atmosphere points to fossil fuel sources. Burning fossil fuels also depletes oxygen and lowers the ratio of oxygen to nitrogen in the atmosphere.”

EV theory can be used as a practical method for weighing the benefits of climate policies by balancing their immediate costs against the long-term advantages for the future. Climate policies, such as transitioning to more renewable energy, often involve short-term costs by investing in research and new technology. However, EV analysis proposes to weigh these immediate costs against the potential long-term benefits it would bring for future people, such as the reduction of existential risks or the preservation of animal species. Take the following simplified hypothetical scenario of how EV calculations could work in carbon emission reduction:

Example

Imagine a government that can choose whether to invest 1 billion euros in a carbon reduction project, which aims to lower CO2 emissions by 100 million metric tons over the next 20 years. The government considers this investment based on the potential reduction of climate-change-related damages in the future. We can now opt for EV calculations to analyze the expected benefits of this project against the short-term costs of investment. But before we can calculate we need to make some assumptions about the future:

- Say 100 million future people could be affected by severe climate-related consequences, such as extreme weather or loss of biodiversity.

- Without government investment, the risk of extreme climate-related events, affecting these 100 million people, is estimated at 10% over the next century.

- If these climate-related events occur, they could result in an estimated economic and social cost of 500 billion euros.

- The 1-billion-euro investment of the government is estimated to reduce the risk of these events by half, from 10% to 5%.

Now we calculate the difference in expected damages with and without the investment.

EV= (Probability) x (Value)

Expected Damages without Investment: EV= 0.10 * 500 billion = 50 billion euros

Expected Damages with Investment: EV= 0.5 * 500 billion= 25 billion euros

So, by investing 1 billion euros in carbon reduction today, this government can expect to save 24 billion euros in the future (25 billion expected savings – 1 billion investment).

The example above shows how EV calculations can help in making rational decisions about the uncertain future. It demonstrates that early climate change mitigation actions can yield substantial long-term value by reducing climate-related events. In the example above we only looked at the economic benefit for future governments, not even taking into account the moral obligation that we have to safeguard the well-being of future people. By adopting the longtermist perspective, we also need to consider how reducing this risk benefits the welfare of those 100 billion people that are still to come.

In conclusion, by applying EV theory to climate change decisions we are able to quantify the benefits of meaningful actions that reduce emissions, thereby protecting our biodiversity and building a sustainable world for our future generations. Through the longtermist perspective, we can frame climate policy as an ethical imperative that sustains the well-being of those who come after us by reducing existential risks and maximizing the potential for thriving human civilizations across centuries to come. However, as with all theories, there are also critiques and limitations of EV theory that need to be discussed.

Critiques and Limitations

Expected Value theory and longtermism might provide a structured approach on how to tackle climate issues, but there are notable critiques and limitations that we need to consider.[8]

1. Uncertainty in Predictions

The biggest challenge of adopting EV theory in a long-term perspective is the inherent uncertainty of predicting probabilities and outcomes for the far future. Climate change is a complex theme involving many dynamic systems, which makes it difficult to establish precise probabilities for potential future scenarios. Different feedback loops, like the melting of ice sheets and the rise of sea levels, may turn out or escalate in different ways than we expect. Critics question whether EV calculations can reliably assign numerical probabilities to such complex phenomena. It requires an ongoing commitment for our generation to keep updating policies based on the evidence we find; this is important to avoid rigid reliance on imperfect models.

2. Present vs Future Interests

Another concern often addressed is the prioritization of future generations at the expense of those currently alive. If we reduce the use of resources for climate change mitigation, then that might result in fewer resources being available for threatening present-day issues like poverty or healthcare. While longtermists like MacAskill argue that we need to prioritize the well-being of future people, critics argue that the well-being of individuals today also holds moral significance and that the uncertainty constraint of the future needs us to focus on the issues that we face today.

Therefore, it is important to keep the immediate needs of those who live today in mind while mitigating long-term existential risks to ensure that neither future nor current populations experience an extra burden. Through continuously revisiting our understanding of climate change risks and adopting a longtermist perspective to represent future generations, we can address both the needs and mitigations required of the present generation and all the future generations that come after us. While EV theory and longtermism might face challenges, they remain important and powerful tools for making impactful moral decisions that also consider the human beings of the future.

Philosophical Exercise 2:

The second philosophical exercise uses Expected Value theory to reflect upon our daily choices.

- Pick a minor decision that you made today. An action or decision that in theory, if more people made that decision, could have a large impact on the future. For instance, walking instead of driving to work, using a reusable cup, or eating vegetarian instead of meat.

- Reflect on the decision you made and ask yourself whether the decision could be improved or whether the decision aligns with your long-term goals.

This reflection helps you to see where your values lie and whether your actions correspond with your values. If they do not match, ask yourself whether the choice is really necessary or if you can change your decisions next time.

- Pascal, Blaise, 1670, Pensées, translated by W. F. Trotter, London: Dent, 1910. ↵

- Bernoulli, D. (1738). Specimen Theoriae Novae de Mensura Sortis. ↵

- Bostrom, N. (2003). Astronomical Waste: The Opportunity Cost of Delayed Technological Development. ↵

- Greaves, Hilary & MacAskill, William (2019). The Case for Strong Longtermism. Gpi Working Paper ↵

- MacAskill, W. (2022). What we owe the future (First edition). Basic Books, Hachette Book Group. ↵

- Buis, A. (2019). The atmosphere: Getting a handle on carbon dioxide - NASA science. NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/earth/climate-change/greenhouse-gases/the-atmosphere-getting-a-handle-on-carbon-dioxide/ ↵

- Buis, A. (2019). The atmosphere: Getting a handle on carbon dioxide - NASA science. NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/earth/climate-change/greenhouse-gases/the-atmosphere-getting-a-handle-on-carbon-dioxide/ ↵

- Zaitchik, A. (2022, October 24). The Heavy Price of Longtermism. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/168047/longtermism-future-humanity-william-macaskill ↵