10 Heidegger’s Forgetfulness of Being

Miriam Prior

I. Heidegger’s Conception of Being

In Being and Time (1927), Martin Heidegger posits a new approach to the concept of Being, setting himself the task of the destruction of philosophical tradition. He argues that people generally exist in an unreflective, everyday mode of being, deeply absorbed in their surroundings and rarely questioning what it truly means to be. Heidegger describes human existence as marked by “thrownness“—from birth, we are thrown into a pre-existing world shaped by social, cultural, and historical norms that we inherit rather than choose. He contends that abstract interpretations and theoretical frameworks often obscure the true nature of Being, reducing it to mere concepts rather than addressing its fundamental essence. Instead of treating Being as a fixed entity, Heidegger frames it as the foundational principle that enables all other things to exist and to be understood. This understanding of Being, he argues, is essential for interpreting and making sense of the world.

The Guardian offers an 8-part essay series that introduces and explores Heidegger’s Being and Time, highlighting its relevance. Part one can be found here.

II. Heidegger’s Critique of Metaphysics

A central element of Heidegger’s critique of metaphysics is the concept of Forgetfulness of Being, which serves as a tool to explain humanity’s estrangement from the essence of its existence. Heidegger argues that our current condition is characterised by an inability to engage with Being itself—where Being is not a specific entity, object, or thing but the very event or process of existence. This forgetfulness arises from our tendency to obscure Being by overlaying it with conceptual frameworks that impose human constructs onto the world, ultimately concealing the deeper reality of existence.

Heidegger critiques the history of philosophy for overshadowing the question of Being, a question that he believes remains not only unanswered but was also unasked. This results in what he calls a double concealment of the question of Being—first by neglecting it outright, and second by covering it over with layers of abstract thought that distance us from its essence.

Heidegger asserts that this forgetfulness is not just a cognitive lapse but rather a fundamental condition of our existence. The distractions of everyday life prevent us from noticing the event of Being, and metaphysical thinking exacerbates this by consistently misrepresenting it. In trying to understand Being, humans impose categories like substance, cause, or energy onto it—concepts that fail to grasp its elusive nature. This is the central error of Western metaphysical traditions, which have led us to distort our relationship with Being itself.

Heidegger’s critique operates on two primary objectives:

- Expose the erroneous and forgetful nature of our metaphysical traditions.

- Aid in the retrieval and remembrance of Being.

Heidegger distinguishes between ontic and ontological knowledge to clarify two different ways of understanding. Ontic knowledge is concerned with the factual study of beings themselves, as in scientific research. Ontological knowledge, however, seeks to understand the Being of beings, engaging with foundational questions typically addressed in metaphysics. Heidegger asserts that Western thought has historically engaged in an onticization of Being—reducing it to specific entities, treating it as a specific kind of being—rather than as an event or process. This ontic approach limits Being to the realm of discrete entities, thereby overlooking its essential nature as the unfolding and revealing of existence.

Heidegger’s concept of Dasein (“being there” or “presence”) refers to the distinctive mode of Being that characterises human existence. Unlike traditional views that see human beings as detached observers of the world, Heidegger defines Dasein as an active participant in the world—capable of questioning existence and creating meaning. Dasein encapsulates the ability to comprehend Being, serving as the mediator through which the true meaning of Being can be uncovered. Heidegger calls for a shift from an objective, detached view of existence to one that prioritises lived experience and the inherent interconnectedness of existence. Crucially, Dasein is not simply the biological individual but represents a communal and shared way of being involving care, both for oneself and for the world. By emphasising Dasein’s ability to engage authentically with Being, Heidegger offers a foundation for overcoming the forgetfulness of Being. Dasein’s capacity for authentic engagement provides the methodological basis for retrieving a more genuine understanding of Being.

III. Forgetfulness of Being Applied as a Philosophical Tool

Ultimately, Heidegger’s “Forgetfulness of Being” challenges contemporary thought, calling for a fundamental shift in how we approach existence. By recognising this “forgetfulness,” we can critically reexamine and transform our understanding of existence, technology, and metaphysics. Heidegger’s theory acts as a philosophical tool, revealing the limitations of metaphysical thought and helping to recover an authentic sense of Being.

To use the tool and apply it to a topic of interest:

- Identify the metaphysical framework of the problem or application in mind. What assumptions are being made about (human) existence and the nature of reality in the context of your topic?

- Do conventional perspectives of the self/being limit how humans engage with the topic? Are traditional views of existence (in nature) limiting engagement with the topic? How is the self viewed in the context—as a detached observer or an active participant?

- Is there any disconnectedness between existence and the topic? Is the topic an isolated issue, or can it be understood in relation to shared existence as a whole?

- How does Dasein transform the experience? After identifying the framework in which the topic exists, how can embracing Dasein shift your interaction with the topic?

IV. Practical Philosophical Exercises

Below are two exercises that aim to foster critical reflection on the use of language and social frameworks. By deconstructing these frameworks, you may cultivate more meaningful interactions with your environment and develop a deeper understanding of what it means to Be.

Dasein in Practice

When in a specific setting—say in a supermarket doing groceries, at a lecture taking notes, or at the gym working out—challenge the experience of being in the world that you are having. Break down the paradigm, and strip away the label of where you are, and what you are doing.

- How does it feel to be in this moment?

- Does it affect how you are experiencing it if you do not project a specific meaning onto it?

This exercise invites you to analyze your habits within social structures and confront how imposed frameworks influence your sense of Being.

Onticization in Practice

Onticization refers to the reduction of complex entities. How does this look in everyday practice? In your daily interactions, with people or objects, think critically about whether or not you are ontizing them.

- For instance, when you are talking with a friend, are you reducing complex emotions to simple labels? How does this affect your experience and perceptions of these emotions?

- Similarly, if you are interacting with an object, consider how you categorise it. Are you viewing it as a static thing, and how does this affect your interaction with it? Instead, try defining the object from an ontological standpoint, focusing on its existence as a process or experience. For instance, a notebook may be seen as merely a collection of blank pages, but it can also represent a process of knowledge and memory.

V. Forgetfulness of Being & Consumerism

Heidegger’s critique is an almost self-evident lens through which the climate crisis can be critically examined. The aforementioned concept of forgetfulness speaks directly to humanity’s estrangement from self-understanding and its relationship with the world. In this context, we can apply Heidegger’s view to reveal deep-rooted existential issues that underpin the current climate crisis. In a consumerism-driven society, the natural world is commodified, overlooking nature’s intrinsic worth and reinforcing the disconnect between humans and their environment. By applying these frameworks, we as humans maintain a psychological distance from a problem we are creating. Ultimately, understanding the climate crisis through Heidegger’s framework reveals it as not just an ecological issue but an existential one.

A. Language EXEMPLIFYING THE DISCONNECT

The language we use to discuss climate issues hints at the metaphysical framework that underlies it. Consider the difference between climate change and climate crisis. The former suggests a neutral, perhaps gradual, process—the climate is simply changing—while the latter conveys a sense of urgency, immediacy, and danger—we are in crisis. Linguistic choices like these are not passive; they both indicate and shape our perception of the natural world and, ultimately, our relationship with it. These contrasting terms do precisely that: reflect deeper assumptions within Western metaphysics. Where climate change, for instance, can reflect a view that natural processes exist independently of human influence, climate crisis suggests an imminent threat that calls for immediate action. This language reveals an underlying worldview where humans are both central stewards and detached observers: an anthropocentric one.

This labeling reveals not only our linguistic preferences but also an ontological divide. Language, for Heidegger, plays a critical role in shaping our experience of Being—language is the Home of Being, it is what can reinforce our ontic perceptions of things. By choosing words, like climate change, that trivialize environmental degradation, we fail to confront the existential implications of our actions. This language dulls the problem’s urgency and reflects a forgetfulness that keeps us disconnected from the real impact of our consumption habits.

B. ANTHROPOCENTRISM AND MECHANISTIC VIEWS OF NATURE

This anthropocentric and detached worldview does not end with language alone. Instead, it extends further into our direct interactions with the world, only further supporting a sense of both entitlement to nature’s goods and separation from the consequences of our actions. The language we use towards the world creates a foundation for an instrumental view of it. Consumerism, a key driver of the climate crisis, is deeply entrenched in traditional perspectives that commodify nature. Essentially, consumer culture treats the environment as a storehouse of resources to meet the demands of a market-driven society. By reducing nature to a series of economic assets, its intrinsic value becomes obscured, viewing it as a means to an end rather than as part of the process of Being. Western culture is rooted in such anthropocentric and mechanistic traditions, where humans are positioned as central to the universe, with nature viewed as separate and mechanistic—a mere background for human activity. From this perspective, nature is valuable only as a resource to be managed or exploited. This mindset is evident in the way we describe aspects of the natural world:

- Cows are sources of milk and meat.

- Rivers provide water supplies.

- Trees are sources of wood.

- Ecosystems are valued for their harvestable resources.

This commodification of nature reflects the ontic approach Heidegger mentions, reducing the world to discrete objects defined solely by their utility to humans. Through this reduction, the essence of nature is concealed, divorcing it from the experience of Being and positioning it instead as a collection of objects for consumption. These reductive views support an instrumental approach to the natural world, which fosters a disconnection that fuels reckless exploitation. Heidegger would argue that this reductionist view denies the fundamental interdependence between humanity and the environment, perpetuating a framework of dominance rather than coexistence. This mindset, which reduces nature to a mere collection of commodities, cultivates a view of climate change as purely an environmental issue—something separate from human experience rather than a crisis threatening the shared essence of life. Viewing nature this way enables us to maintain a certain psychological distance, preventing a fuller engagement with the real implications of environmental degradation for human existence.

C. Moving toward an authentic relationship with Being in nature

From a Heideggerian perspective, addressing the climate crisis meaningfully requires moving beyond these self-serving frameworks of anthropocentrism, commodification, and consumerism. By acknowledging but also challenging our estrangement from nature and the causes of it, we can rediscover our existence as it truly is: embedded within a world that deserves care and respect for its own sake. The issue of climate change is more than scientific; it is a breakdown of existence, exposing the limitations of our current consumerist paradigm. The question, then, is far more profound than mitigating the effects of climate change. Instead, we should ask ourselves: What is our proper and fundamental relationship to the natural world? And in turn, how do we retrieve it?

VI. Visualising the disconnect

This chapter shows that Forgetfulness of Being in modern existence can obscure the richness of what it means to exist by superficial and detached constructs. As a consequence, humans have become abstracted from the world around them. This forgetfulness manifests not just philosophically but can also be seen in daily life. Forgetfulness affects how we perceive and interact with the world and each other. This section explores Forgetfulness of Being through a series of pictures to bridge the gap between philosophy and the real world. These photographs aim to serve as various interpretations of Being in nature and in modern settings.

Note: I chose photography and particularly the curation of images, as it is something I have always enjoyed seeing when going to museums. For this assignment, I went out to take pictures in Groningen but also used pictures I already had from previous trips. Together this makes a small curated set of images I believe well represent Forgetfulness of Being and our relation to nature. All pictures were taken by me on a Sony a6400 camera and edited and resized in GIMP.

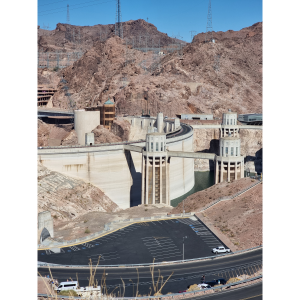

The Hoover Dam, USA, 2024

The Hoover Dam, located on the border of Nevada and Arizona in the USA, is one of the largest dams in the world. An immense feat of human industrial engineering in the heart of the desert, this massive concrete structure captures humanity’s imposition on nature. Nature is seen as a resource to be conquered rather than a presence in itself.

Chi Q’aq’, Guatemala, 2024

Tourists ascend and take pictures of Volcán Acatenango and Chi Q’aq’ (also known as Volcán de Fuego), seeking experience. But in this process, the true essence of the volcano is blurred. The volcano’s nature is replaced by the human desire to conquer and consume it rather than witness its existence.

Street Lamps in Flores, Guatemala, 2024

The streets that line Lake Petén Itza on the island of Flores, Guatemala, have been flooded during the rainy season. The water has engulfed the street lamps, showing how fragile human imposition on the natural world can be. If nature chooses the resurge, humans have no power against it.

The Stadsstrand, Groningen, The Netherlands 2024

During the summer, the city beach in Groningen is packed. Yet, once the temperatures get cooler, swimmers seldom frequent it. In this picture, the absence of people highlights how social frameworks can alter the state of being of a place. But beyond what humans assign, nature will persist in its own right.

National Gallery Prague, Czech Republic, 2024

The National Gallery Prague is one of my favourite museums. This picture shows the grand hallway, bare, empty and almost repellent. This scene, directly opposing the previous image of The Stadsstrand, shows how artificial and institutional settings lose their essence without those who frequent them. The white walls and empty couches appear devoid of meaning when no visitors are around. As humans, we create structures, but for them to have meaning, they must be filled.

North Sea, Denmark, 2024

My close friend sits on a pier above restless waters. Her presence is isolated as an observer of the natural world. However, she is not part of it, but instead sits atop a human-made pier. Nature is boundless, but she is bound to human-made structures.

Deodorized Central Mass with Satellites photographed at the MoMA, New York, USA, 2024

Deodorized Central Mass with Satellites by Mike Kelley is a work that criticizes consumer culture. Kelley uses stuffed animals, symbols of childhood comfort discarded with age and bought from thrift stores, to create a central hanging mass and surrounding satellites. The toys’ faces are sown inwards so that visitors cannot see them and so they do not elicit an emotional reaction. The central mass is surrounded by ten sculptures that release pine-scented mist into the air to hide the scent of second-hand toys. The stuffed animals in this sculpture have lost their original essence and have been discarded as part of the consumer cycle. Faceless and deodorized, Kelley confronts us with our tendency to avoid uncomfortable truths. Find out more about the piece here.

References

Heidegger, M. (2010). Being and time. SUNY press.

Guzun, M. (2014). Eternal return and the metaphysics of presence: a critical reading of Heidegger’s Nietzsche.

Baggini, J., & Fosl, P. S. (2010). The philosopher’s toolkit : a compendium of philosophical concepts and methods (2nd ed). Wiley-Blackwell. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=312278

Wheeler, Michael, “Martin Heidegger”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/heidegger/>.