3 Fallacies

Andras Kesz and Wander Jorritsma

Introduction

Climate change is inarguably one of the most pressing issues of today’s world. Countless studies, reports, directives, and manifestos have been published in the last decades. Unfortunately, there are those voices who, despite the mountain of evidence, deny the threat of climate change. These people, often prominent members of the public, spread misinformation and deceive the public. This chapter aims to uncover the underlying faults in their arguments and to showcase some of the deceiving tricks they use to deliver their arguments.

How do climate change deniers fail to make valid claims? The brief answer is: fallacies. Scholars Baggini and Fosl define fallacies as products of faulty reasoning.[1] Naturally, this is quite a broad definition. You might think there are a lot of different ways in which someone’s argument could be flawed. The Wikipedia page on fallacies lists over a hundred different kinds. Covering all would be beyond the scope of this project, so we have focused on four specific fallacies committed in the debate around climate change. Before we go into more details about the individual fallacies, it is important to make the distinction between what structurally divides them. Baggini and Fosl differentiate between two types of fallacies, formal and informal.[2]

Formal fallacies are those where the fault lies in the form or structure of the argument. The individual premises of such faulty arguments might be correct, and the mistake typically occurs when drawing the conclusion. One of the most common formal fallacies is called ‘affirming the consequent’. The authors gives a hypothetical scenario to illustrate this. Imagine we knew that if Fiona won the lottery, she would be driving a red Ferrari today. Then we see her drive by in a red Ferrari. Now if we concluded that Fiona won the lottery, we would commit a formal fallacy. It is true that Fiona is driving the car right now, and it might even be true that she would be driving the Ferrari if she won the lottery; however, we cannot conclude from this that she actually did win the lottery. For all we know she might have inherited a large sum of money or decided to steal the car.[3]

On the contrary, the conclusion of an informal fallacy might be perfectly valid, while something in the content of the premises is fallacious. The most common informal fallacy and the one mentioned by Baggini and Fosl is the ‘gambler’s fallacy’. Imagine a gambler is betting on the tossing of a die.[4] At a certain point the die has not landed on six for quite a while, which the gambler finds suspicious. He believes it is due for a six to be cast. However, what he fails to understand is that each next throw is unaffected by the one before it. If the gambler believes that the next die roll has a chance over one in six, he is committing an informal fallacy. His conclusion is validly drawn from his premises; however, the content of the premises themselves is fallacious. No mistake is made in the logical structure of the argument. If his premise that die rolls are affected by previous ones is true, then his conclusion that the next die roll is more likely to be six is true as well. However, his premise that the casting of a die is affected by previous rolls is plainly wrong.[5]

Fallacies of climate change

The category of fallacies is too broad to apply to a certain subject. Since there is an abundance of specific fallacies, it is important to narrow down the scope of our inquiry to some that will be useful. The following sections will briefly introduce some of these fallacies, which will then be used in our discussion of arguments concerning climate change.

Ad hominem fallacies

The ‘Ad hominem’ argument is rooted in an attack against a person or group, rather than what they say. As George Wrisley notes, “it is an argument that calls into question a person’s character, her credibility and trustworthiness, by appealing directly to some negative aspect of her person, or indirectly by making some negative claim about the person’s relationships, actions past or present, commitments, views, or still more.”[6] While the ad hominem fallacy has numerous branches, they share the above definition. It is important to note that not all uses of ad hominem arguments are fallacious, as there can be legitimate reasons to question someone’s personal bias.[7] Especially in politics, it can be an effective tool to highlight some personal, possibly corrupt connections. Did the politician say that fracking is dangerous because she has business interest in the solar sector? There are valid questions to be raised there. Moreover, we could say “We shouldn’t trust his opinion on climate change, because his wife is the head of an oil drilling firm.” This is not necessarily a fallacious argument because it raises sound doubts about the person’s objectivity. Ad hominem arguments might question the validity of the other person’s claims by criticizing them. In the second part of this chapter, I will present discussions from both sides of the political divide that employ ad hominem arguments, often fallaciously.

Misleading statistics

“Misleading statistics refer to data points, figures, or visual representations that are inaccurate, false, or manipulated to convey a distorted or biased message. They often arise from errors or biases in the collection, organization, or presentation of data.”[8] The intentional use of misleading data is to confuse or, as the name suggests, mislead the audience. It can host a range of biases, from selective fallacies such as cherry picking to misleading visualization such as skewed graphs to establishing faulty correlations.[9] The connection between misleading statistics and climate change might already be intuitive. Climate scientists often present graphs, statistics, or predictions; these can be the target of manipulation, misrepresentation, or distortion. How this is done exactly is going to be the subject of the second part of this chapter.

Bothsiderism

The fallacy of bothsiderism has been coined a few years ago by Scott Aikin and John Casey.[10] The fallacy is committed when an individual assumes a disagreement on an issue should be resolved by compromise, should not be judged or needs further discussion. The example given by Aikin and Casey is a disagreement over the existence of gods. Imagine there are two friends: Xena and Hector. Xena is an atheist, so she argues there are no gods. Hector on the other hand is an Olympian, which means he believes in the existence of exactly twelve gods. After a long discussion, neither is convinced by the other’s arguments, so Hector offers a compromise. He says: “It is unreasonable of you to believe that I am completely wrong just as it would be unreasonable for me to believe you are completely wrong. So why don’t we meet in the middle? How about six gods?”[11] The conclusion is hilarious as much as it is absurd: there is no reason to assume the truth lies in the middle. This is where the fallacy lends its name. It is the ungrounded belief that there is something to say for both sides of the argument.

Invincible ignorance fallacy

Also commonly named the argument by pigheadedness, the invincible ignorance fallacy is committed when one party simply refuses to believe an argument or refuses to accept evidence given, without valid reason. It was first coined in 1959 by Ward and Holther.[12] An example of this would be to claim “I believe X no matter what you say,” where you close the door to any critical discussion. Another example would be when someone would claim something to be fake news without any reason. In more recent times Van Eemeren en Garssen wrote about the ‘Obligation to Defend Rule’.[13] Simply put, everyone in a critical debate has the obligation to defend their position to all attacks put forward by the opponent. According to Van Eemeren en Garssen, when someone refuses to follow this (or any other of their rules), then they have committed a fallacy.[14]

Key Takeaways

- Ad hominem arguments target the person, rather then their claims

- If the personal attack is irrelevant or unfounded → Fallacy!

- If the personal attack uncovers potential conflict of interest → (potentially) Good!

- Misleading statistics intentionally misuse data, usually through visual misrepresentation

- : Check the context of information, look out for small study sample sizes, and make sure to consult multiple sources

- Bothsiderism: The fallacy of bothsiderism is committed when someone mistakenly believes that disagreement on an issue means that it (1) should be resolved by compromise, (2) should not be judged or (3) needs further discussion.

- Invincible ignorance fallacy: The invincible ignorance fallacy is committed when someone refuses to defend their beliefs while also not letting go of these beliefs.

Climate change on social media

Written by Andras Kesz

I think it is safe to say that social media has its defects when it comes to reporting on facts. There is academic consensus that the spread of misinformation on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter (X) can have dramatic consequences. The intentional spread of false or misleading news on the topic of public health, for example, has resulted in the death of many during the Covid-19 pandemic.[15] I believe that when it comes to misinformation about climate change, we deal with the same kind of existential threat, but on a longer term. The coming sections of this chapter will look into how former US President Donald Trump, someone who has repeatedly called the issue a hoax, has been sharing his opinion about the climate problem on his Twitter account. Since this chapter deals with fallacies, I will look at some of the fallacious arguments he has committed over the last decade.

Climate change is not a hoax!

This chapter, as well as others in this book, treat climate change as a fact. This view is in line with the overwhelming scientific evidence that is available today. The phenomenon refers to long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns. It results in rising average temperatures and extreme weather events such as floods, hurricanes, droughts. To learn more about the basics of climate change, visit the United Nations information page on the issue.

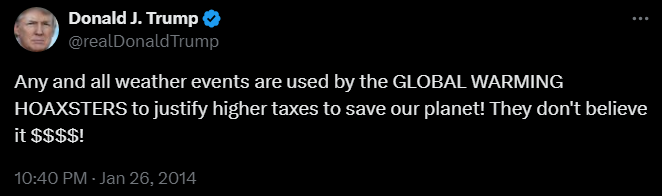

Is it unfair to put the former (and since re-elected) President’s words under the microscope and criticise his stance on climate? Shortly, my answer is no. His position as first a prominent businessman, then President of the globe’s largest economy, and inbetween the strongman of the whole Republican Party, puts him in a highly influential position. His words reach tens of millions of people. His public position represents a source of authority. His ideas regarding an issue such as climate change will shape American climate policy for four extra years. For over a decade now, Trump has shared a worrying number of tweets questioning climate change. One type of fallacy which was discussed during the first part of this chapter deals with ad hominem attacks. Instead of focusing on the argument, the one committing the fallacy questions the character or motive of the other. Now let us turn to some of the tweets President Trump has shared that fall into this category.

Here, Trump claims in capital letters how those (undisclosed who exactly, probably referring to the Obama administration at the time) who believe that climate change is a problem, only pretend to believe so in order to raise corporate taxes and benefit their own wallets. This tweet is a key example of a fallacious ad hominem argument. Trump wrongfully accuses the administration, suggesting that their opinion on climate change is irrelevant since they have an underlying financial interest in it.

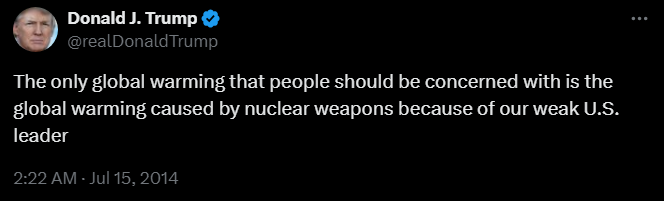

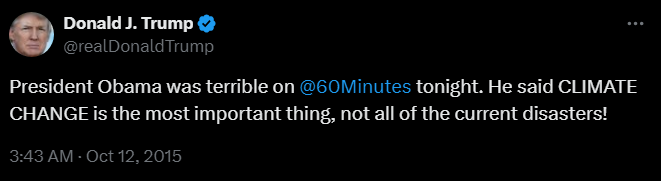

In the tweet above, Trump dismisses worries about climate change not because they are false, but because he sees the Obama administration as weak.

In a similar vein, instead of questioning its relevancy, the point of attack is President Obama’s performance. In these last two tweets, Trump makes him seem an incompetent and weak leader, which is only indirectly connected to the issue of climate change. He also fails to recognise the long-term threat climate change presents as he criticises Obama for not seeing short-term problems. Similarly to my findings, some scholars have highlighted how Trump’s Twitter strategy was consciously built and focused on putting his political rivals in a negative light.[16][17] Fallacious ad hominem attacks offer him a way to criticise his opponents without directly addressing their arguments.

Exercise #1

As mentioned before, ad hominem attacks often accuse one party of their personal interests interfering with their judgement. Often, these are unfounded allegations, but sometimes they can raise valid points. Politicians can be accused of conflicting financial interests; a representative denying climate change might have large amounts of investments in an oil company, or another might advocate for a big solar expansion while having stocks in solar energy companies.

- First: Identify an ad hominem attack related to conflicting financial interests

- Second: Check if such a connection actually exists, with platforms such as capitoltrades.com

- Third: Ask yourself whether there is truly a conflict of interest, and if it is right for politicians to trade and legislate

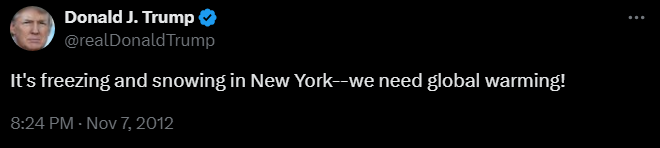

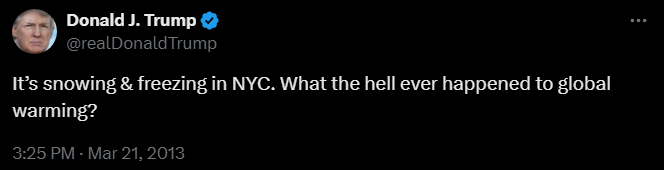

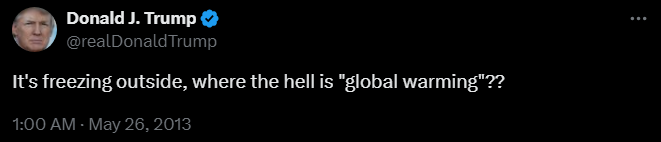

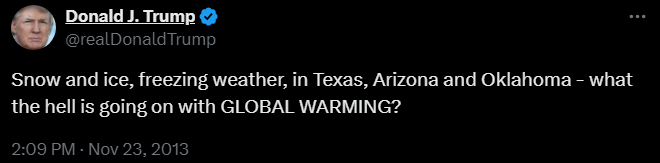

The first section of the chapter also introduced the concept of misleading statistics. This refers to the misuse of data, usually through visual misrepresentation. While Trump has rarely posted any visual graphs that might fall into this trap, he has used weather data in a fallacious sense through ‘cherry picking’. It manifests itself in his recurring suggestion that the presence of cold weather would somehow disprove global warming. Below, I have included only a limited number of his posts about this, although he makes this fallacy at least a dozen other times.

Note: Climate change is concerned with long-term patterns, and not individual weather events. Global warming refers to the increase in the planet’s overall average temperature. It outlines average tendencies, rather than single occurrences.

Cherry picking certain days when the temperature happens to be colder than expected grossly misrepresents the true argument of global warming, and in effect climate change. It also disregards other aspects of climate change, such as the increased number of hurricanes, tornadoes, forest fires, droughts, and so on. Having an unusually cold day during fall or spring, as highlighted in the tweets, precisely shows how traditional seasonal observations can be disrupted by changing weather patterns. Looking at such tweets, I wonder whether Trump actually understands the concept of climate change and global warming. Naturally, we should not commit the type of ad hominem fallacy that he readily applies in his rhetoric. It is a perfectly conceivable and strong political strategy to spread confusion about the definition of such terms, to confuse the intuitions of voters, and make policies accordingly. This phenomenon is not exclusive to Trump, nor to the United States. Although I have only analysed this context, the reader can certainly find climate skeptic voices within their own country. For this reason, recognising and understanding what fallacies people commit can help you avoid being misled.

Exercise #2

Cherry picking specific instances from a big pool of data can be used to justify misleading points. This is not only the case in connection with climate change.

- Try to think beyond climate change, and find examples in other areas, such as migration, gender inequality, or poverty

Climate change on television and YouTube

Written by Wander Jorritsma

In debates on television and YouTube the objective is often to convince a third party: the viewer. With this comes a myriad of problems, since the goal is no longer to find a solution. The aim instead becomes to persuade the audience of your standpoint, often regardless of truth or science. This gives rise to a multitude of fallacies being committed. Unsurprisingly, these fallacies appear in debates on climate change as well. In this part I will show the fallacy of bothsiderism and the invincible ignorance fallacy committed in several debates on television and YouTube.

Bothsiderism

As explained earlier, the fallacy of bothsiderism is committed when an individual mistakenly believes a disagreement on an issue means it (1) should be resolved by compromise, (2) should not be judged or (3) needs further discussion.[18] I will present a video for each of these ways in which the fallacy is committed within the debate on climate change.

Let us start with the first one, when an individual believes the disagreement should be resolved by compromise. This part of the fallacy has often been presented as its own fallacy, commonly known as the middle ground fallacy or the argument to moderation. One example I found is from the Lex Fridman Podcast. In the podcast Lex Fridman starts by describing two extreme opposite views in the debate around climate change and states that he would love to find the center. The fallacy is committed because Lex Fridman assumes the truth lies in the middle between climate change being a hoax and climate change causing the end of human civilization. He believes we should resolve these two different views by finding a compromise, instead of accepting the idea that the truth leans more towards one side of the disagreement.

The second way one can commit the fallacy of bothsiderism is by suspending judgment on a disagreement while there is clearly one side that is true. One example of this can be seen when in 2020 on PBS NewsHour senator Kamala Harris interrogates judge Amy Coney Barrett. She first asks Barrett whether she believes Covid-19 is infectious and whether smoking causes cancer. After an irritated Barrett agrees with these claims, Harris asks whether she believes climate change is happening, to which Barrett responds that she will not express a view on the matter. Her reasoning is that a judge should not comment on matters of public policy. Yet Barrett had no problem agreeing with trivial scientific facts about the infectiousness of Covid-19 or smoking inducing cancer. Suspending judgment on a scientific fact like climate change is a clear example of the fallacy of bothsiderism.

The last way in which someone can commit the fallacy of bothsiderism is when they believe the topic needs further discussion, even though there clearly is no need. Commonly this happens when the topic of debate is on whether or not climate change is caused by humans. In these cases one party rightfully claims that the debate is over: scientists have researched this and concluded that climate change is caused by humans. The other party might argue against the mountain of evidence and state that it is unclear whether or not humans are the cause: they think further discussion is necessary. This is the case in this next clip from Fox News, where climate skeptic Tucker Carlson argues with Bill Nye and claims the cause of climate change is still an open question. He argues we can only settle the question when we can say to what specific degree humans cause climate change.

One question to ask ourselves is why this fallacy is being committed in the first place. Why do these people believe we should resolve the disagreement by compromise? Why do they suspend judgment or claim further discussion is needed? One answer could be that by digging their heels in the sand, they are able to shift the public’s view towards the side they agree with. For instance, they might not actually believe that climate change is a hoax, but by presenting that view they might convince the public to shift their opinions towards non-renewable energy sources. Another answer would be that by not giving up ground they ensure we are not able to discuss the real issue: what we are going to do about climate change. Because of these reasons it is not only the people who hold these views that are to blame, it is the networks themselves as well. This was addressed in HBO’s Last Week Tonight, where John Oliver humorously shows a statistically accurate representation of the debate. They claim that 97% of scientists believe that climate change is caused by humans and show what that debate should actually look like on television.

Exercise #3

The fallacy of bothsiderism is committed when someone mistakenly believes that disagreement on an issue means it (1) should be resolved by compromise, (2) should not be judged or (3) needs further discussion.

- First: Write on a sign: “I believe climate change is caused by humans: let’s talk.”

- Second: Go to a busy square with your newly made sign.

- Third: Argue with whoever starts a conversation with you. Do they commit the bothsiderism fallacy? If so, which specific one?

Invincible ignorance fallacy

As written above, the invincible ignorance fallacy is committed when someone refuses to defend their belief while also not letting go of their belief. In regular discourse you usually have a reason to believe your view and if someone challenges that belief, you can either agree with them and drop the belief, or you can defend your position by countering their argument. Thus, when someone does not defend their belief, yet also does not drop their belief, they commit the invincible ignorance fallacy.

An example of this is from the Joe Rogan Experience, when Joe Rogan has Candice Owens on as a guest. Out of character, Joe Rogan appears as the reasonable one, as Owens states she does not believe in climate change. Rogan mentions that the vast majority of scientists agree that climate change is negatively affected by humans, to which Owens responds that she “just does not think so.” By not giving a counter argument, Owens runs from her obligation to defend her belief, committing the invincible ignorance fallacy.

Later on in the same interview, Joe Rogan pulls up a study that claims the vast majority of scientists agree that climate change is driven by human activity. Candace Owens throws the evidence aside, stating that she only believes in studies with the web domain ‘.org’. After this they find a similar study from a site with the web domain ‘.org’ to which she responds: “I personally don’t believe it: that’s okay.” In the clip below, she once again clearly ignores her obligation to defend her belief, again committing the invincible ignorance fallacy.

Exercises #4

The invincible ignorance fallacy is committed when someone is unwilling to defend their position. They say the best way to learn is by doing. So why not try the fallacy out yourself?

- First: Make a claim that your friend, family member or colleague disagrees with, baiting them into a debate.

- Second: Listen as they give an argument why your claim is wrong.

- Third: Ignore whatever argument they make. Do not defend your position!

- Fourth: Notice how they respond. Do they keep explaining their viewpoint? Or do they mention your obligation to defend?

Tip: Afterwards you could mention to your friends, family or coworkers that you were merely trying out the invincible ignorance fallacy. The relief of you not being a pigheaded fool might outweigh the anguish of you being a philosophy enthusiast.

- Peter S. Fosl and Julian Baggini, The Philosopher’s Toolkit: A Compendium of Philosophical Concepts and Methods (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2020), p. 23. ↵

- The Philosopher’s Toolkit, p. 23 ↵

- The Philosopher’s Toolkit, p. 23 ↵

- The Philosopher’s Toolkit, p. 25 ↵

- The Philosopher’s Toolkit, p. 25 ↵

- Robert Arp, Steven Barbone, and Michael Bruce, Bad Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Fallacies in Western Philosophy (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2019), p. 72 ↵

- Bad Arguments, p. 73. ↵

- Hassan Ud-deen, “Misleading Statistics & Data: How to Protect Yourself against Bad Statistics,” Klipfolio, April 9, 2023, https://www.klipfolio.com/blog/how-to-spot-misleading-data. ↵

- "Misleading Statistics," Klipfolio. ↵

- Scott F. Aikin and John P. Casey, “Bothsiderism,” Argumentation 36, no. 2 (January 2022): 249–68, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-021-09563-1. ↵

- “Bothsiderism,” pp. 249–250. ↵

- W. W. Fearnside and William B. Holther, Fallacy the Counterfeit of Argument (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1959). ↵

- Frans H. van Eemeren and Bart Garssen, “The Pragma-Dialectical Approach to the Fallacies Revisited,” Argumentation 37, no. 2 (2023): 167–80, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-023-09605-w. ↵

- "The Pragma-Dialectical Approach," p. 169. ↵

- Sadiq Muhammed T and Saji K. Mathew, “The Disaster of Misinformation: A Review of Research in Social Media,” International Journal of Data Science and Analytics 13, no. 4 (February 2022): 271–85, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-022-00311-6. ↵

- Yini Zhang et al., “Attention and Amplification in the Hybrid Media System: The Composition and Activity of Donald Trump’s Twitter Following during the 2016 Presidential Election,” New Media & Society 20, no. 9 (December 2017): 3161–82, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817744390. ↵

- Francis Badiang Oloko, “Analyzing Donald Trump’s Global Warming Communication,” Bergen Language and Linguistics Studies 13, no. 1 (August 2023), https://doi.org/10.15845/bells.v13i1.3707. ↵

- "Bothsiderism," pp. 249–268. ↵