16 Class Critique

Chiara Pregely and Mandy Roelfs

Class critique is a philosophical tool that is used for criticizing concepts and theories in terms of how they reinforce or undermine class hierarchies or contribute to class conflict (Baggini & Fosl, 2010, p. 222). This philosophical tool is mainly used by philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their theory of Marxism. In this theory, Marx and Engels make a distinction between two economic classes that are in constant conflict with each other. According to them, every event in history is a consequence of these class conflicts. Even though this is the most popular formulation of class critique, they were not the only ones who used this approach. Other thinkers came up with their own formulations, like Immanuel Wallerstein in his world-systems theory. Instead of making a distinction between classes, his theory is more of a global approach in which there is a hierarchy between areas or states.

Let’s take a look and delve into these two theories. They will show in a more tangible way what is meant by ‘class critique’.

marx and engels on Class conflict – Mandy roelfs

In their political pamphlet The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848) wrote: ‘The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles’. What they mean by this is that every event in history and the developments of society are based on a conflict between the classes in this society. A conflict between the classes is always about getting materialistic or economic benefits.

But what determines which class you belong to? According to Marx and Engels, the class you belong to is determined by your role in the economy. More specifically, by your role in the production process. In the modern capitalist economy, there are two main classes: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The bourgeoisie, also known as the capitalist class, is the class that owns the means of production, like factories and machines. They also purchase the labour power of others. These ‘others’ are the proletariat, who are also known as the working class. They sell their labour to the bourgeoisie in exchange for wages. However, the bourgeoisie retains most of the profits that the proletariat has produced with their labour. In other words, the proletariat is exploited because they only receive a small part of their profits, while the bourgeoisie gets richer at their expense. We can see that both classes have different goals. The bourgeoisie wants to maximize their profits, while the proletariat wants to maximize their wages and working conditions. Both classes consider their own benefit more important, which leads to a contradiction. This manifests itself in a conflict in which the proletariat rebels against the bourgeoisie, which, according to Marx and Engels, will eventually be won by the proletariat (Van Peperstraten, 1991, p. 121).

These conflicts do not only occur on the economic level, which is called the ‘substructure’ in the theory of Marxism. They are also present in other parts of the society, such as on the political, religious and cultural levels. These levels together are called the ‘superstructure’. The substructure percolates, as it were, through the superstructure which is built upon it, while we do not realize this. How we should understand this is that the economic class you belong to determines your view of the world, and with that it is determinant for politics, religion, culture, and all of the other parts of society, while we are not aware of it (Baggini & Fosl, 2010, p. 223). For instance, according to Marx and Engels, we do not realize that there is a class conflict underneath the establishment of liberal political rights, such as the freedom of expression and the right to vote. According to them, these rights were in reality established for the richer, ruling class because it was in their own interest (Baggini & Fosl, 2010, p. 223). However, we have adopted the false belief that these rights were developed for the rest of the people and for the sake of fostering equality.

More examples of class conflict in the superstructure (Baggini & Fosl, 2010, pp. 223-224):

- According to Marx, the motivation behind the US Civil war was not the abolition of slavery, but to expand capitalism in the South of the US.

- According to Marxists, the Reformation did not necessarily happen because of religious motives, but it was a tool to establish a new capitalist way of thinking that put emphasis on individualism.

- Many have argued that the Iraq War was not fought to protect people or to uphold the sovereignty of small nations, but to exert influence and control over a particular area that has a great geopolitical position and would ensure access to oil.

When we look at the climate crisis through this Marxist lens of class critique, it too can be seen as a class struggle that makes the richer class richer at the expense of the working class. This will be shown in more detail later, when applying the tool of class critique to the specific case of climate change.

wallerstein’s World-systems theory – chiara pregely

We have seen how Marx and Engels describe class struggle in the production process where the classes are the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. In Marx‘s theory, the class you are in is defined by your role in the production process. This definition of class is a social one, then. We will now look at a more global approach to class struggle, namely the world-systems theory. Here you could define class as a more area-based economic class. This approach is created by Immanuel Wallerstein, but he does not mention the term ‘class’.

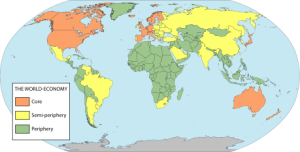

Wallerstein’s understanding of the world as it is now, starts with the uprising of the capitalist world economy

(Chirot & Hall, p. 84). In this world economy, the market began to have the most influence on productivity (Chirot & Hall, p. 84). Within the capitalist world economy, there is a hierarchy between different areas, namely the core states, periphery areas and semi-periphery areas. Core states are the most advantaged areas and the periphery areas are the least advantaged (Wallerstein, p. 608). Core states have core productions, which means that it is controlled by quasi-monopolies (Eckhardt, p. 96). Quasi-monopolies are when one company dominates over a certain product and this domination has support from the state (Eckhardt, p. 96). Periphery areas have a periphery production, which means that it is controlled by a competitive structure and is weaker or more unstable than the core production (Wallerstein, 2004, p. 28). In the next quote from Chirot and Hall (p. 85), it is explained how the core states and periphery areas are related to each other.

This world-economy developed a core with well-developed towns, flourishing manufacturing, technologically progressive agriculture, skilled and relatively well-paid labor, and high investment. But the core needed peripheries from which to extract the surplus that fueled expansion. Peripheries produced certain key primary goods while their towns withered, labor became coerced in order to keep down the costs of production, technology stagnated, labor remained unskilled or even became less skilled, and capital, rather than accumulating, was withdrawn toward the core.

This relation shows us that the core states feed off the periphery areas, which keeps the core states rich and the periphery states poor. Core states take cheap labor and cheap resources from periphery areas and keep most of the profits for themselves. This way, the core states keep thriving and the periphery areas stay in their economic place. The areas sustain each other, so there is a balance, but the balance is off since one area benefits more than the other. Thus, the core states dominate the periphery areas (Wallerstein, p. 195). The economic power difference between the two only increases over the years (Chirot & Hall, p. 85). This uneven score is one of the main components of capitalism according to Wallerstein (Chirot & Hall, p. 85).

There is also a third and middle group in the hierarchy, namely the semi-periphery areas. These have aspects that are in between the core states and the periphery areas (Wallerstein, p. 609). These areas can later become either a core state or a periphery area (Wallerstein, p. 609).

You could interpret this dynamic between the core states and the periphery areas as a class struggle. This may not be the social class struggle Marx describes within the production process, but a more global class struggle. The areas mentioned can be seen as classes in the sense that one area dominates the other area. This is just another level of looking at class struggle. The workers in one country can still be in the same class as workers in another country, while being in another class area wise. The two theories of Marx and Wallerstein do not cancel each other out. Marx argues that the class conflict within the substructure percolates through the superstructure. This can also be stated within Wallerstein’s theory. The economic class conflict the areas find themselves in can determine much more beyond just the economic level. Poorer areas can for example not invest as much in infrastructure, education or more fair and non-corrupt politics as richer areas can. Richer areas have more power, for example to be able to improve public transport and education. It is important to note that in Wallerstein’s theory these three classes can change in status (Christofis, p. 5). Thus, the periphery area can become a core state and escape its domination. Wallerstein argues though that capitalism inherently needs an uneven scale, so there must always be core states and periphery areas to sustain each other’s economic status (Christofis, p. 5).

So, Marx and Engels describe class critique as a class conflict between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, which initially takes place at the substructure, but which flows through to all of the other parts of society: the superstructure. Wallerstein, on the other hand, gives an analysis of capitalism as a world economy that can be seen as class struggle as well, but with classes seen as areas rather than groups of individuals. The core states dominate and exploit the periphery areas, just like the bourgeoisie dominates and exploits the proletariat. On the other hand, the periphery areas also need the core states for work and for income, the same way the proletariat need the bourgeoisie. This is how they keep each other in place.

Applications of Class critique to climate change

How can we apply these theories of class critique to climate change? We will use class critique to analyze two different topics closely related to climate change: the right to housing and the food industry.

The right to housing – Chiara Pregely

Climate change causes a lot of consequences for the world. One of these consequences is less living space for animals and humans. Here, we will focus on the consequences of climate change for our living space, but it is important to note that animals also suffer from our actions in relation to climate change. The human right to housing is an internationally-acknowledged right, but this is endangered by the effects of climate change. We view our living space as something holy, something we should protect and respect. It is a safe space, which is endangered by climate change, in this case. Class critique could offer an interesting analysis of this problem on another level.

Climate change and the right to housing

The human right to adequate housing is a fundamental human right and it is acknowledged internationally in human rights law (UN-habitat). Having a house also means access to basic services like a shower, warmth, a bed, etc. A house is a safe space and it means security and dignity (The Shift, 2024). We see it as a basic and fundamental right everyone should have. Everyone deserves a safe space. It does not matter what your race, ethnicity, age, religion or sex is. Unfortunately, there are a lot of people that do not have a home. According to UN habitat, there are 1.8 billion people in the world that do not have adequate housing. Adequate housing means for example having security, that the house is habitable and that it is affordable in relation to your income (The Shift, Glossary).

Climate change is a big factor in this housing problem. Due to the rising global temperature, more extreme natural disasters happen more often, for example floods, earthquakes, wildfires, drought and storms. These natural disasters all impact people’s daily lives and specifically our living space. Climate change increases the intensity and frequency of these natural disasters. There are a couple of consequences that we should highlight in relation to housing. First, natural disasters can destroy houses and wipe them from the Earth. Second, in addition to destroying houses, climate change can also slow the reconstruction of houses. Shipments and supplies are harder to get, for example because they are disrupted by natural disasters (Morrison, 2023). Third, the delay of supplies also has an economic effect, namely the rise in prices. A consequence of the rising costs is that many people cannot afford (re)building or buying/renting a house (Morrison, 2023). Fourth, if there are less houses being built, the houses that do get built, will get more expensive (Morrison, 2023). Fifth, the increase of natural disasters and growing need of rebuilding means that the house insurances also get more expensive (Morrison, 2023). Thus, people also cannot afford to take precautionary measures for their houses anymore. From these five consequences, we can conclude that climate change impacts us in our most precious space, namely our homes, in many different ways. To sum up, climate change impacts our homes not only physically, but also economically. Our human right to housing is therefore being endangered by climate change.

Class critique of the right to housing

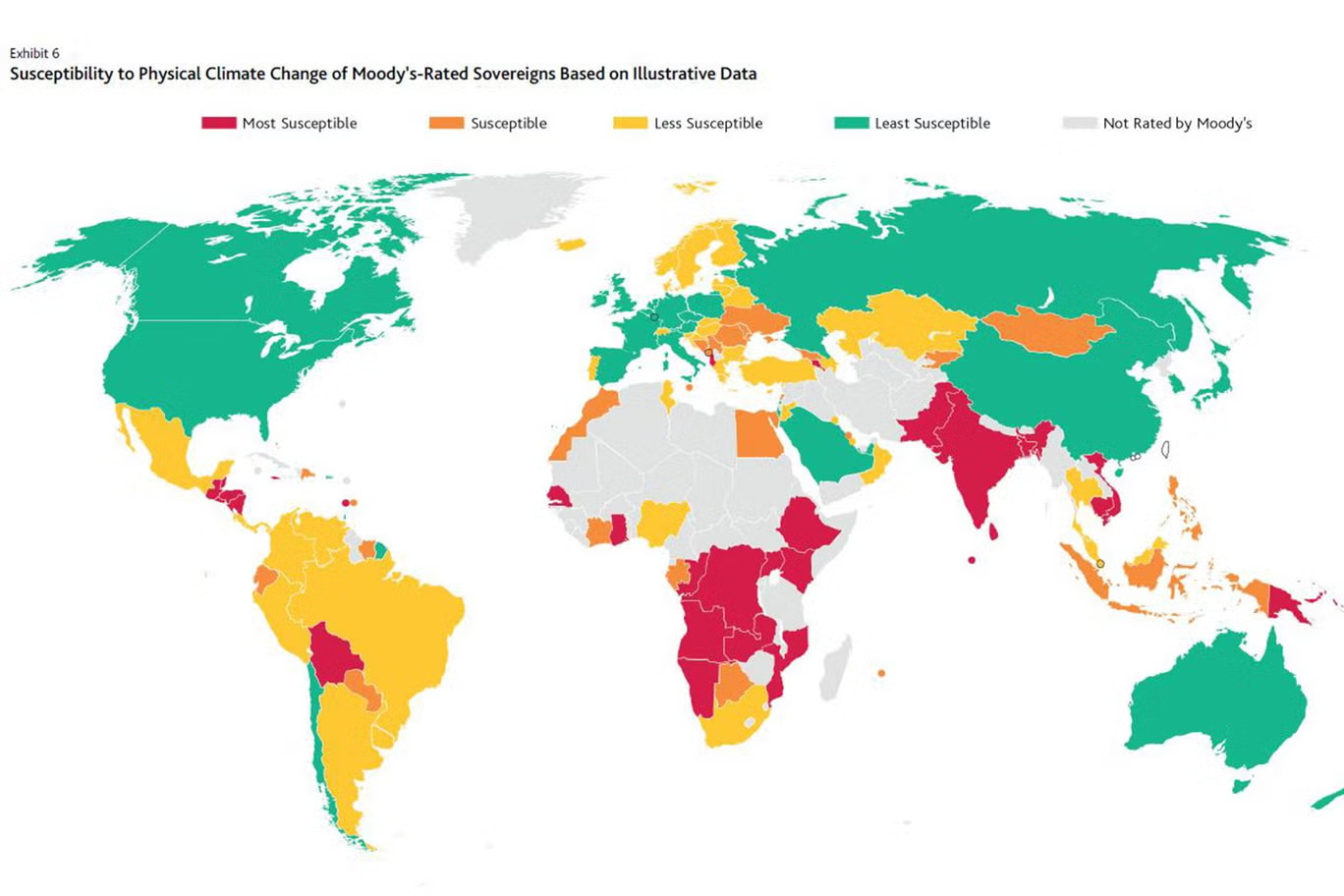

We can use class critique to see the underlying power or class conflict within a certain concept. That concept could undermine or reinforce class hierarchy. Class critique will help analyze this problem climate change produces in respect to the right to housing. In this application, we look at Wallerstein’s world-systems theory First, we look at how the classes are divided when we talk about climate change. The higher and richer class, the so called core states, would be the areas where the consequences of climate change are the least noticeable. The lower and poorer class, namely the periphery areas, would be the areas that are more at risk due to climate change. The areas that may not be that prosperous could lose more due to the consequences of climate change. These areas may already not have the best supplies or opportunities. The periphery areas also do not have the money to rebuild or protect themselves against the consequences of climate change. The core states do have these resources at their disposal.

On the map you can see which countries will be most at risk in relation to climate change and which countries are less at risk. This coincides more or less with the class division I sketched above.

Now, how does climate change reinforce the class hierarchy? As is said in an article of The United Nations (2022), ‘climate change exacerbates existing vulnerabilities’. The periphery areas, thus the poorer countries, already have a disadvantage, which is being intensified by climate change. Climate change keeps the lower class poor and leaves them at the mercy of the higher class, since climate change mostly affects the vulnerable class and they do not have the resources to (re)build, with the vulnerable class being the periphery areas and the higher class being the core states.

Therefore, the periphery areas cannot grow, they can barely catch up. The core states stay rich; since these countries endure fewer effects of climate change, there is less money that they need to spend on rebuilding and there is more room to grow. It is even the case that the core states, thus the richer countries, are the heavy polluters. For example, core states have better and more roads to increase mobility with cars, which increases CO2 emissions. When we look at factories, not all the industrial factories of richer countries are in their own countries. It may be cheaper to have your factory in other countries. So, either the core state is the heavy polluter and does not bear the biggest consequences, or the core state has its factories in a poorer country, which is cheaper for the core state, and that periphery area in which the factory is placed has more pollution consequences. The consequences of this heavy pollution fall again mostly on the poorer areas. Richer countries may not want to reduce their CO2 emissions, since their economic and societal stability depends on them. This makes it harder to reduce pollution, which maintains the state of the poorer countries experiencing more physical risks of climate change. On the other hand, the poorer countries also need services from the richer countries, for example employment, which maintains this unfair balance.

What does this mean for the right to housing? Countries that already have a hard time providing sufficient and adequate housing, will have more trouble with this. The class critique version based on Wallerstein shows that climate change maintains the class hierarchy, specifically in the right to housing. Periphery areas do not have the resources to (re)build adequate houses. The houses that do get (re)built are destroyed by the reinforced natural disasters due to climate change. The houses of people in core states are safe(r) from these natural disasters, while they are in general the heavy polluters. The right to housing is for everyone and it seems now that it is only for the higher class. This should not be the case. We should not let climate change reinforce the hierarchy; we should go against it. We should unite powers and fight against climate change while ensuring everyone is safe from the consequences of climate change. Especially for our houses, which are seen as people’s safe space. Everyone deserves a space to feel safe in.

The Food Industry – Mandy Roelfs

How does the food industry contribute to climate change?

The food industry is one of the leading causes of climate change and nature loss worldwide (Oerlemans, 2023). This food industry is dominated by four agro-industrial multinationals, namely ADM, Bunge, Cargill and Dreyfus, who want to operate on as large a scale as possible to maximize their profits. A few examples of what these multinationals do are manufacturing fertilizers, pesticides and animal feed, providing farmers with seeds, transporting food around the world, and processing meat on a large scale. Besides that, they control the largest stocks and 70% of the grain trade. Other layers of the food industry, like farmers, are dependent on them because these multinationals have a monopoly on products that the farmers need in order to do their job. Long story short: these multinationals control the production, processing and distribution of food (PVDA, 2024).

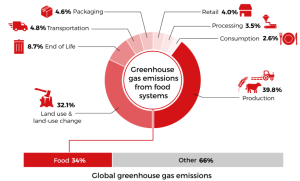

However, this large-scale way of working contributes to destroying the Earth. The food industry is, among other things, responsible for nearly one-third of total greenhouse gas emissions, which leads to global warming. Greenhouse gasses emitted by the food industry are mainly CO2, methane and nitrogen. CO2 is emitted primarily from agriculture, transportation and processing food in factories. Methane and nitrogen are mainly emitted by livestock farming, and using and storing fertilizers. In addition, pesticides used to protect crops cause pollution of water and air. There is also a lot of deforestation because a large amount of agricultural land is needed to raise livestock and grow crops, which further contributes to CO2 emissions and the loss of biodiversity (World Wide Fund for nature, z.d.). These are just a few examples of many more, but it demonstrates how the current food industry is polluting our earth and contributing to climate change.

big wheels are turning,

four companies are smiling,

while nature is dying.

– Mandy Roelfs

How is the food industry affected by climate change?

Not only is the food industry one of the main causes of climate change, but it is also being affected by climate change. We see that farmers increasingly face harvest failures due to the increase of extreme weather conditions, like prolonged droughts, excessive rainfall or heatwaves (Hufstader, 2024; Oerlemans, 2023; Vork, 2021). In 2022, 85% of cropland in Ethiopia and 60% of the grain production in Somalia was affected by a two-year drought (Hufstader, 2024). These extreme weather conditions are a result of climate pollution, to which the food industry is a major contributor. The effects of climate change harm the agricultural yields of farmers and this leads to financial uncertainty. They not only lose their income, but in some cases they are also forced to give up their farmland because it is their only chance to survive. These effects are felt by farmers around the whole world, but especially by small-scale farmers in the poorest countries. It has been predicted that around 2050, African agricultural yields could fall by 30% due to climate change (Hufstader, 2024). These farmers already earn meager wages, and because of crop failures they have lower yields and are finding it harder to make ends meet. They are among the least responsible for the emissions. Yet, they do get hit the hardest. If no changes are made, they will get hit even harder and more frequently. It is predicted that by 2100, rice yields could drop as much as 50% compared to 1990. Wheat and maize production could drop by 30% in South Asia (Hufstader, 2024). This in turn leads to more problems, not only for farmers but for consumers too. Think about food insecurity, food shortages, and famines.

land is in decay

farmers left empty-handed

for rains stay away

– Mandy Roelfs

A conflict between agro-industrial multinationals and farmers

The signs of climate change are thus becoming more and more obvious, which is why there is a growing number of protests against current practices in the food industry and a demand for the industry to become more sustainable (Boerderij, 2024; Oxfam Novib, 2024). Research by Nieuwe Oogst found that three-quarters of the farmers in The Netherlands want to become more sustainable (Bouwmeester, De La Court & De Snoo, 2022). But for farmers, putting this into practice is not that easy. As shown in the beginning of this paragraph, farmers are dependent on agro-industrial multinationals that dominate the food industry. Farmers cannot decide themselves how to farm. They have to comply with the requirements set by the multinationals. On top of that, they cannot finance a sustainable way of farming themselves. The farmers are, as it were, trapped in a system that works against them (Milieudefensie, 2024).

In politics, more and more plans are being made to make the food industry more sustainable, but agro-industrial multinationals disagree with these plans and are doing everything they can to block their implementation (RTL Nieuws, 2022). Unlike many farmers, it is actually to their advantage to continue with the current polluting way of food production because they profit from this.

The application of Marx and Engels’ class critique

How can we analyze this situation with the use of class critique? We can approach this situation by means of Marx and Engels’ theory. When we look at this case, we can distinguish between two classes, the one richer than the other, with different interests that conflict with each other.

On the one hand, there are agro-industrial multinationals that dominate the climate-polluting food industry. These multinationals can be seen as the bourgeoisie that Marx and Engels talk about. The bourgeoisie is at the top of the capital system, just like the agro-industrial multinationals dominate the food industry. They own the means of production, like factories, machines, and other products like fertilizers and seeds that the lower classes need in order to do their job. Because of their monopoly power, they also determine the food prices on the market. Their only real interest is to maximize their profit. They do this by maintaining the current way of large-scale food production, which contributes to climate change and nature loss. Hardly anyone has heard of these companies, but they are extremely powerful. To make it more concrete, I will zoom in on one of these multinationals: Cargill.

‘Cargill has built the modern agriculture system – with all its abuses’ – Glenn Hurowitz

One of the agro-industrial multinationals is Cargill. You have probably never heard of them, but the odds are high that you have some of their products in your pantry. It is the largest trader and producer of food ingredients and agricultural products in the world. ‘We are the flour in your bread, the wheat in your noodles, the salt on your fries’, begins one of their slogans (Jordan, Ross, Howard, Heal, Wasley, Thomas, & Milliken, 2020). But the way they operate, using monoculture and large-scale transportation, is destroying our planet. Products we bought used to come from farmers near us. But Cargill is one of those responsible for ensuring that we often do not know where our food comes from (Jordan et al., 2020). It is responsible for the large-scale, polluting way of producing food. Among other things, their company is largely responsible for agricultural pollution, such as the pollution of water and air by their pesticides and fertilizers. They have also been linked to deforestation, such as the deforestation of the Cerrado, which is an important ecosystem. They are doing all these things for one purpose: profit. The Cargill family gets richer and richer every day. To put it concretely, between 2020 and 2022, the Cargill family earned $20 million a day and currently their wealth is $33.4 billion (PVDA, 2024). As they get rich, they gain more power and they use this power, in turn, to get a higher profit by for example taking over land and farms from small farmers. This is all at the expense of the climate and farmers, who suffer from the climate change that companies like Cargill largely contribute to.

On the other hand, there are farmers who are dependent on these multinationals for their seeds, machines, fertilizers, and pesticides, which reduces their autonomy. The farmers can be seen as the proletariat in the theory of Marxism. They do the hard, physical work of producing crops and livestock farming. They are already receiving a small part of their profits, because the largest part goes to agro-industrial multinationals and middlemen such as supermarkets (Public Food, 2024). But on top of that, they are harmed even more by climate change, to which the food industry is a large contributor. The farmers are the victims of the power of the multinationals. They are just small pawns in the larger, polluting food industry that is controlled and maintained by these large multinationals. It is difficult for farmers to do anything about their circumstances since they do not have the money or power to do anything about the lack of sustainability in the food industry, or even to make their own way of producing more sustainable. In the meantime they are hit harder and more frequently by climate changes, which eventually makes them even poorer.

So, we see that the multinationals (bourgeoisie) benefit from the climate-polluting food industry, while the farmers (proletariat) suffer from it. They both have different goals. The multinationals want a profit as high as possible, while the farmers want better wages and working conditions. However, these goals conflict with each other. This is the conflict in the substructure that Marx and Engels talked about, which underpins what happens in the superstructure. In the superstructure, there is a struggle going on regarding the climate crisis. Here, the multinationals want to stop making the food industry more sustainable because sustainability is detrimental to their profits, while most farmers want a more sustainable food industry because it is more favorable to their harvests and therefore to their wages and working conditions. At this moment, the multinationals still have the upper hand in this situation. How we can see this is that climate change maintains the hierarchy of classes and even widens the gap between those classes. The climate-polluting food industry keeps making the bourgeoisie richer, while climate change makes the proletariat poorer. To end this chapter on a positive note: farmers should not lose hope. There is a growing number of protests, and changes are slowly happening (Klimaatakkoord, 2022), just like Marx and Engels predicted.

the polluting food industry

led to a struggle about sustainability.

which turned out to be a class conflict

just like Marx and Engels predict.

for mighty companies grow rich as climates heat

while poor farmers can’t make ends meet.

– Mandy Roelfs

PHILOsophical exercises

- Look at the news and consider whether the topic could be related to conflicts between classes or maintaining the hierarchy between classes. Ask yourself the following questions: Which classes are involved? In what way is the hierarchy of the classes maintained or how does it contribute to class conflict?

- The conflict between agro-industrial multinationals and (small-scale) farmers regarding the climate crisis is not the only way to see class struggle in the food industry. Can you find another class struggle? Think about the clash between agro-industrial multinationals and consumers (with a low income). Can you better approach it with Marx and Engels’ theory or with Wallerstein’s theory? And how?

- Roleplay: play an existing trading board game of your choosing with a group of people, for example Catan. Divide the group into core states, periphery areas and semi-periphery areas. How would you play the board game in character as your area? Would you help each other with problems? And how? After this round, change roles. How would you play the game now? (How) would you help each other? Think about the nature of human beings, their relations, and of the hierarchy. Is it fair how we behave? Could we make it more fair?

- While reading about the right to housing, it might be hard to imagine not having to worry about this problem. With this exercise, I want you to try to take a different perspective. Imagine having to work very hard for your house and for keeping it. Then, image it being taken away from you by the consequences of climate change. Think about how you would feel and why having a home is so important.

References

Baggini, J., & Fosl, P. (2010). The philosopher’s toolkit : a compendium of philosophical concepts and methods. 2nd ed. Chichester, West Sussex ; Malden, MA : Wiley-Blackwell.

Boerderij (2024). Protest tegen handelsverdrag met Zuid-Amerika, meer acties op komst. Retrieved from https://www.boerderij.nl/protest-duurzame-boeren-tegen-eu-handelsverdrag-met-zuid-amerika

Bouwmeester, R., De La Court, J., & De Snoo, E. (2022). Driekwart van de boeren wil verduurzamen. Retrieved from https://www.nieuweoogst.nl/nieuws/2022/08/13/driekwart-van-de-boeren-wil-verduurzamen#:~:text=Nederland%20heeft%20geen%20stikstofprobleem.,over%20verduurzaming%20van%20de%20landbouw

Chirot, D., & Hall, T. (1982). World system theory. Annual Reviews. Vol. 8:81-106.

Christofis, N. (2019). World-Systems Theory. 10.1007/978-3-319-74336-3_372-1.

Eckhardt, I. (2005). Review of World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction. 1 st Edition, by I. Wallerstein. Perspectives, 25, 95–98.

Hufstader, C. (2024). How will climate change affect agriculture? Retrieved from https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/stories/how-will-climate-change-affect-agriculture/

Jordan, L., Ross, A., Howard, E., Heal, A., Wasley, A., Thomas, P., & Milliken, A. (2020). Cargill: the company feeding the world by helping destroy the planet. Retrieved from https://unearthed.greenpeace.org/2020/11/25/cargill-deforestation-agriculture-history-pollution/

Klimaatakkoord (2022). Hoofdlijnen klimaatbeleid voor landbouw en -gebruik. Retrieved from https://www.klimaatakkoord.nl/actueel/nieuws/2022/06/02/hoofdlijnen-klimaatbeleid-voor-landbouw-en–gebruik

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1848). The Communist Manifesto.

Milieudefensie (2024). Bevrijd onze boeren van hebzucht agro-industrie. Retrieved from https://milieudefensie.nl/actueel/bevrijd-onze-boeren-van-hebzucht-agro-industrie

Morrison, R. (2023). How Are the Climate Crisis and the Housing Crisis Related? Accessed 14 October 2024

7 Ways in Which Climate Change and the Housing Crisis Are Related | Earth.Org

Oerlemans, N. (2023). Voedsel en landbouw eindelijk onderdeel van de klimaatafspraken?. Retrieved from https://www.wwf.nl/wat-we-doen/actueel/blog/natasja/voedsel-landbouw-onderdeel-klimaatafspraken#:~:text=Voedselproductie%20en%20%2Dconsumptie%20behoren%20tot,ook%20hard%20geraakt%20door%20klimaatverandering

Oxfam Novib (2024). Oxfam Novib steunt boeren in een eerlijke en duurzame transitie. Retrieved from https://www.oxfamnovib.nl/blogs/dilemmas-en-oplossingen/oxfam-novib-steunt-boeren-in-een-eerlijke-en-duurzame-transitie

Public Food (2024). Meer weten. Retrieved from https://publicfood.org/en/missie/

PVDA (2024). De giganten van de agro-industrie die de wereld uithongeren en kleine boeren uitbuiten. Retrieved from https://www.pvda.be/nieuws/de-giganten-van-de-agro-industrie-die-de-wereld-uithongeren-en-kleine-boeren-uitbuiten

RTL Nieuws (2022). Milieuvriendelijker boeren? Daar steken grote bedrijven graag een stokje voorhttps://www.wwf.nl/wat-we-doen/focus/klimaatverandering/oorzaken-gevolgen-klimaat. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ycEdZ0sYteY

The Shift (2024). Right to housing. Accessed 12 October 2024.

Right To Housing – The Shift (make-the-shift.org)

The Shift (2024). Glossary- Human Right to Adequate Housing. Accessed 13 October 2024

Glossary – The Shift (make-the-shift.org)

The United nations (2022). Climate change and the right to housing: Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing. Accessed 14 October 2024.

Climate change and the right to housing | OHCHR

UN-Habitat, Housing rights, Accessed 13 October 2024

Housing Rights | UN-Habitat (unhabitat.org)

Van Peperstraten, F. (1991). Samenleving ter discussie. Een inleiding in de sociale filosofie. Bussum: Uitgeverij Coutinho.

Vork (2021). Landbouwopbrengsten groeien minder snel door klimaatverandering. https://www.vork.org/artikel/698782-landbouwopbrengsten-groeien-minder-snel-door-klimaatverandering/

Wallerstein, I. (2004). World-systems analysis : An introduction. Duke University Press

Wallerstein, I. (2011). The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century (1st ed.). University of California Press.

World Wide Fund for nature (z.d.). Oorzaken en gevolgen klimaatverandering. Retrieved from https://www.wwf.nl/wat-we-doen/focus/klimaatverandering/oorzaken-gevolgen-klimaat