13 Jamesian Critique of Belief- And Action-Adoption

Climate change is a huge, complex issue with many interlocking facets. It is therefore not something one can solve by oneself or that one is confronted with by oneself; it is a shared, social problem of general public interest.

Seriously combatting climate change can and will have consequences for public life one way or another. Although the ways in which our lives are impacted may differ along lines of socioeconomic class, place of residence, and occupational differences, it is undeniable that we will all feel the impact of climate change and our efforts to mitigate it. This will inevitably be a source of some kind of friction in our daily lives as we are forced to adapt.

This may mean that we have to change the way we go about our daily lives. From big to small, from the way we earn a living to the groceries we choose to buy at the supermarket, things will have to change somewhere, somehow. In other words, changing something about climate change will have to be accompanied by changes in our everyday practices, our actions.

On the other hand, these changes in action do not fall out of the sky randomly or come to us through divine revelation (for most of us, at least). We have beliefs about our actions, about the reasons for them, and about their expected outcomes. So, we might therefore say that doing something about climate change requires adaptation both in terms of belief and in terms of action. They will have to go hand in hand.

-

Introducing the Philosophical Tool

In his essay The Will to Believe, pragmatist philosopher and psychologist William James presents a theory of belief that revolves around the concept of making a “leap of faith” when empirical evidence is inconclusive or unavailable. Written at the turn of the 20th century, this essay challenges the classical notion that beliefs should be held only when supported by sufficient evidence, a position traditionally associated with the empirical philosophy of logical positivism.

Instead, James argues that when we face certain types of decisions, particularly those concerning matters of personal or existential significance, we are justified in adopting beliefs based on practical considerations, even when evidence alone does not compel us to do so.

James’ argument for the will to believe hinges on several core ideas. The most crucial is that certain decisions involve genuine options—those that are live, forced, and momentous. A live option is one where both the belief in a proposition and the belief in its negation are equally plausible to the person considering it. A forced option presents two mutually exclusive alternatives, leaving no middle ground. Finally, a momentous option is one that is significant enough to irreversibly change the direction of a person’s life, or whenever a choice revolves around one-time opportunities. When all three conditions apply, James argues that we have a right to believe in absence and anticipation of conclusive rational, logical, scientific proof. Importantly, for James, belief before certainty might in fact help establish the truth of the matter in question. But the reverse can also be the case. In a sense, beliefs can function almost like self-fulfilling prophecies according to him. We will return to this point later.

The essay itself primarily addresses religious belief, but the ideas contained within it are far-reaching, applicable to many situations in which individuals are called to make important decisions under uncertainty. Climate change, as one of the defining existential crises of our time, is a case where these philosophical considerations are deeply relevant.

Other Key Authors and Works

In case you want to get a fuller picture of William James’ thought or learn more about the things other pragmatist philosophers have said about the interrelated issues of belief, truth, and practice, here are some suggestions for further reading:

- William James – The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy (1896) and Pragmatism (1907).

- There are also some decent YouTube videos covering James’ philosophy, like this one, or this one.

- John Dewey – The Public and Its Problems (1927) builds on James’ ideas to explore how public beliefs and actions are shaped.

- Charles Sanders Peirce – The Fixation of Belief (1877) outlines Peirce’s theory of belief formation and how we come to hold convictions.

- Richard Rorty – What’s The Use of Truth? (1998) explores Rorty’s pragmatic view of truth, suggesting that truth should be seen not as an objective or static property but as a tool for social cooperation and problem-solving.

2.1. Climate Change as a Momentous, Forced, and Live Option

Climate change presents a genuine option in the sense that it is a belief that can significantly impact our individual and collective futures. The question is not whether the belief in climate change is conclusively proven by every possible scientific detail, but whether the consequences of acting on it are so momentous and urgent that belief is warranted as a pragmatic tool for change.

Thus, the Jamesian framework can be used to fruitfully reflect on our belief-adoption and decision-making with regard to climate change and its mitigation even if we were to disregard the persuasiveness and overwhelming amount of scientific evidence showing that climate change is real and is partially caused by us.

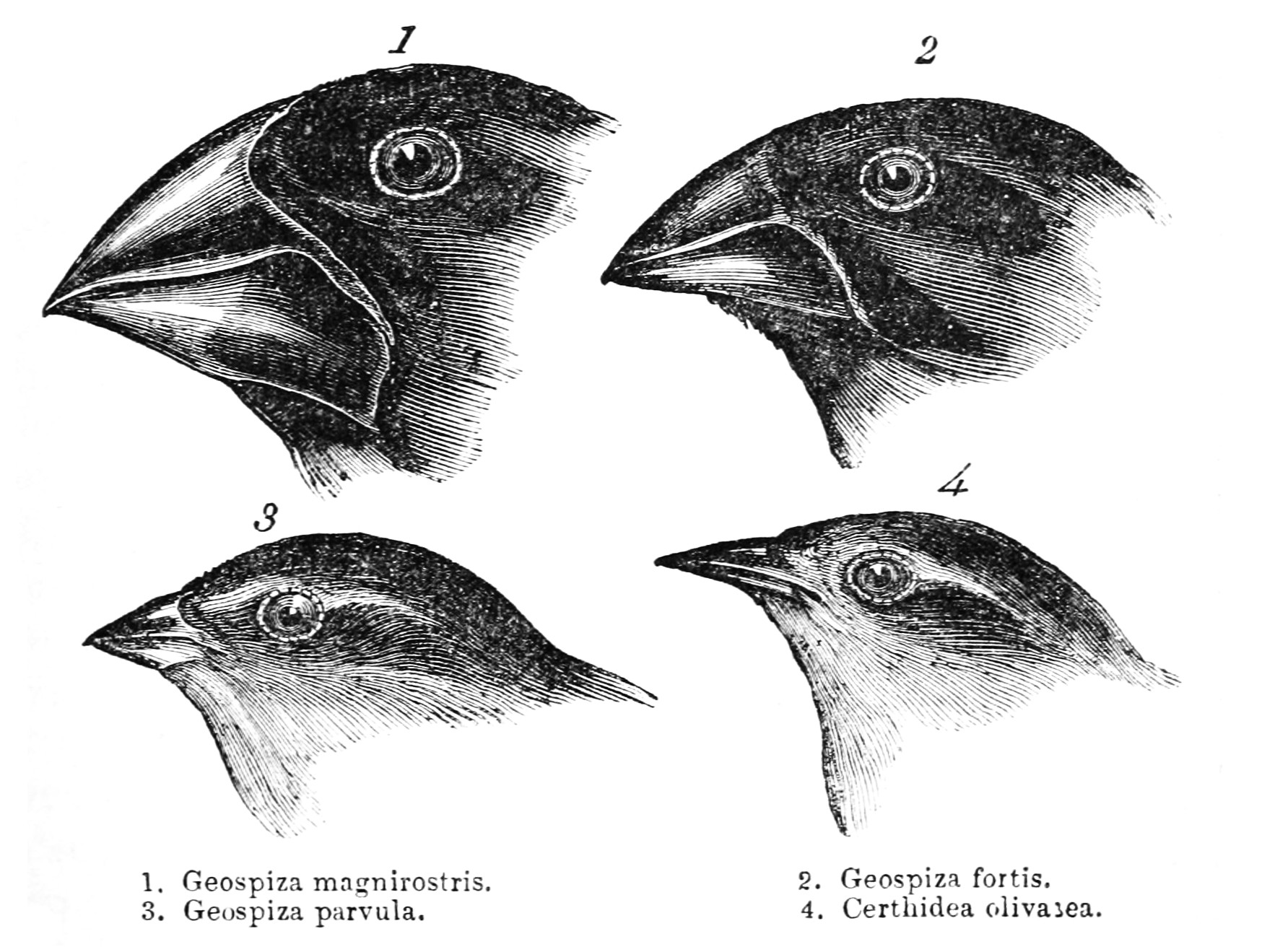

Drawing on James’ theory, we can determine if climate change is a genuine option, like an ornithologist might distinguish between species of birds.

- Live: Climate change is a live issue in that it is a matter of global urgency with real, immediate consequences for individuals, communities, and (nonhuman) ecosystems. The belief in climate change and its potential catastrophic impacts is something that people across the world have to decide whether or not to accept.

- Forced: The option to believe in climate change is forced because there are two clear, mutually exclusive positions: one can either accept the reality of climate change and act accordingly, or deny it and face the risk of ignoring potentially disastrous consequences. Denial of climate change is not just simply a theoretical position; it has real-world implications for policy, community, and individual behavior.

- Momentous: The decision to believe in climate change is momentous because the consequences of either believing or not-believing it can irreversibly shape the future of not just humanity but life on Earth. If we choose to believe in the reality of climate change and act on it, we are likely to adopt policies, behaviors, and technologies that address environmental issues and mitigate risks. If we fail to believe it, we risk exacerbating global warming and facing irreversible damage to ecosystems, economies, and societies.

In other words, James’ pragmatism helps us understand why, in the case of climate change, belief is not merely a matter of intellectual assent. The relevance of his analysis is in showing that belief-adoption is an active and practical decision. Belief itself can become a way of driving action.

When confronted with the evidence of climate change, individuals may feel overwhelmed by the complexity of the data. It is easy to start feeling lost and uncertain about the future, with no clear direction. However, adopting the belief in climate change, even in the face of uncertainties or imperfect evidence, can serve as a pragmatic response to a global crisis. This belief may push individuals to take action—such as reducing their carbon footprint, voting for climate-conscious policies, or supporting renewable energy—that helps address the challenge. The act of believing can itself open the door to actions that contribute to environmental sustainability.

Just as James argued that individuals have a right to believe in religious matters based on the existential stakes involved, so too do we have a right to adopt the belief in climate change. The stakes are high: the health of the planet, the survival of species, and the well-being of future generations depend on our ability to address climate issues. Inaction or denial of climate change, based on a purely skeptical or evidence-based approach, can be seen as irresponsible in the face of such high stakes.

2.3. Let Us Look at It in a Different Way

Is any of this really relevant or useful in relation to climate change?

That is a good question. After all, James’ argument pertains specifically to the rational legitimacy of religious beliefs. And is it not the case that climate change is a very well-researched phenomenon? If James’ point in The Will to Believe is about belief in advance of evidence, why would it be relevant to an issue that has such an overwhelming amount of supportive academic work dedicated to it? In this case, I would argue that the very fact that there is such a thing as climate change denial is due to the fact that, for one reason or another, there are (groups of) people that refuse to decide on the issue on purely intellectual grounds.

Because they refuse to recognize the sheer volume and strength of the evidence for climate change, James’ analysis of the relationship between passion and reason becomes relevant to the issue. In other words, James’ critique may be helpful precisely because it gives us tools that can help us understand the emotive, imaginative, psychological dynamics that go into belief-adoption. If we can somehow make use of these levers as presented by James, perhaps we can bring others who would otherwise reject the pressing nature of the climate crisis to reconsider their perspective. So, how can we appeal constructively to the these elements? Let us try a thought experiment that allows us to reflect on a genuine option in a completely different scenario:

Belief and Action as Basis for Truth, Skepticism as Harmful and Paralyzing Source of Anxiety

Suppose you’re a philosopher who loves rock climbing—it’s a fairly common combination, I’m told, although I don’t know why, so don’t ask me, please. Let’s say that you’re quite the daredevil, even. Like that guy who Free Solo’d the El Capitan in Yosemite Park and had a documentary made about it.Imagine yourself doing what he did, ‘free solo’ climbing (meaning no use of equipment, except some chalk) straight up into the sky along more than two thousand meters of granite. All alone.

There you are. If there was anyone around to see it, when viewed from down in the valley you would look about the size of an ant. Slowly, you crawl your way up the mountain-sized wall. As the sun is starting to set, you find yourself stranded on a narrow ledge, already hundreds of meters above the valley below. The climb has been long and exhausting, and now there’s only one way out: you have to make a jump to another ledge. The gap isn’t that large, three—maybe four—meters. But the rocks are angled awkwardly, and you can’t tell for sure if you’ll be able to make it. Doubt clouds your mind. What if you miss and fall? Involuntarily, you see flashing before your eyes the image of your leap. Barely covering the distance. The slipping of your grip. The plunge to your death.

Sitting there quietly contemplating your predicament, you for some reason suddenly recall when you first learned about René Descartes’ method of doubt—how, according to him, only things that can be indubitably known are true. In this case, you cannot know with certainty that you can make the jump. Religiously relying on this kind of skepticism, you should assume you can’t. The reasonable conclusion, based on doubt, would be to stay put, to wait for help. Even though it might never come. The possibility of succumbing here of thirst, seems just as real as jumping and plummeting to your death.

Another thought arises—what if, instead of doubting, you chose to have faith despite these doubts? The doubts remain undeniable, but if you decide to act on mere faith and the willingness to believe in absence of being guaranteed a good outcome, trusting that your body might have the strength to carry you, you might just be able to do it. Right? Right, okay.

Your palms are sweaty. Your mind starts racing. You stand up, your hands shaking, and focus on the ledge ahead. Instinctively, your body braces itself.

You jump.

For a moment, it seems as if you’re falling. But your hands find the rock. You grip the ledge and pull yourself up, gasping for air. You made it. You’re alive.

Looking back, you wonder: had your belief, “I can do this,” been true before you jumped? Before you actually leapt, you had no way of knowing the thought to be true. All you could do is assume the belief based on faith. And yet the same leap without the faith might have been performed half-heartedly and resulted in your death. Through the act of believing, you helped create the conditions for the belief to become true. Descartes could argue all he wants that your belief couldn’t be ‘true knowledge’ because it contained more than a small element of uncertainty. But your belief became true in a different way. It wasn’t about certainty; it was about acting on the possibility.

By believing in your ability to make the jump, you helped turn that belief into a reality. The truth wasn’t something you could prove beforehand, but something you created through your action.

Now, any sane person with a strong sense of self-preservation—hopefully, this is you, dear reader—might respond to all of this by saying that free soloing is maybe just not the best idea. You would of course be right. Yet life has a tendency to unexpectedly throw up its own kinds of seemingly insurmountable problems. Life has its El Capitans. And when—not if—this happens, I’m positive our philosopher-rock climber will tell you that it is vital to dare make a leap of faith from time to time.

Lesson: Belief can be a Foundation for Discovering Truths

The commonality between the thought experiment above and the issue of climate change James’ analysis of genuine options allows us to see is that, in certain situations, belief isn’t merely a passive acceptance of facts but an active choice that shapes our lived reality. When evidence is lacking, belief in advance of certainty-beyond-doubt can become a guiding force that leads us to new truths—truths not accessible through skepticism alone.

In this thought experiment, belief doesn’t just reflect reality—it helps create it. As James argues, belief can be the foundation for discovering new truths, particularly in areas where empirical evidence is unavailable. By acting on belief, we engage with the world in a way that leads to new understandings and experiences. Thus, in some cases, climate change included, the act of believing itself can be the basis for finding truth, and not simply a passive reflection of an already established reality.

2.5. More Philosophical Exercises

Of course, effectively combating climate change will in large part depend on making meaningful changes on global, institutional, and governmental levels. It is not an issue a single person or community can independently solve. And yet, activism on the personal, local level is essential. To get a clearer picture of how to apply James’ The Will to Believe to the issue of climate change on a more individual, personal level, here are a few exercises readers can engage with.

I. Explore the Consequences of Belief

II. Discuss the Right to Believe

Engage in a discussion about the “right to believe” in relation to climate change. If possible, try to find a conversation partner who is inclined, for whatever reason, to deny the reality of climate change, or to deny the relevance of human impact on it. Consider and discuss whether people who deny climate change have a right to do so, and under what circumstances their denial might be justified or harmful. How does James’ framework of “forced” and “momentous” options apply to this situation? Could you use what we have discussed to make apparent to your conversation partner that, perhaps regardless of whether we think evidence for climate change is conclusive and persuasive, the stakes relating to climate change are just too high to sit by idly? Can you at least make them sympathize with the idea?

III. Consider whether Your Actions Match Your Beliefs

-

Conclusion

William James’ The Will to Believe provides a philosophical tool that helps us navigate the uncertain terrain of climate change belief and action. It reminds us that belief is not just a matter of intellectual assent but a pragmatic choice that can shape the actions we take in the face of global challenges. By understanding and applying James’ ideas, we can better appreciate how belief in climate change drives personal and collective efforts to confront one of the most pressing issues of our time.

The upshot of the Jamesian analysis, and the thought experiment and the exercises, is that they do not need to assume our discursive opponents to already agree with or believe in the truth of our own position. In this way, my hope is that this chapter might aid those who seek to establish meaningful, constructive discourse between parties of differing convictions—and lead not only to fruitful discussions of whether or not we should believe in the truth of climate change, but also bring into the fore the more concrete, psychological, practical, and, if you will, “human” aspects of each one of us having to decide on the matter for ourselves.

References

- James, ‘The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy’, Cambridge University Press, (1896), ISBN: 978-1-10806723-2

- Miller, ‘James’s Doctrine of “The Right to Believe”, in The Philosophical Review, Vol. 51, No. 6, pp. 541-558, Duke University Press, (1942), URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2180939