9 Husserl’s Phenomenological Conception of Knowledge

Knowledge as Fulfillment to Fight Climate Change

Nathan Santema

Introduction

If you listen to both songs and compare them in your mind, what do you notice?

Of all the noticeable differences, one is that the songs are likely very different in terms of the feeling they invoke in you. To me, one is slow and creepy, like flowing down a scary river. The other is fast and fun, which gets more and more derailed as it moves on. If I ask you to analyze the difference more closely, what would the root cause of this difference be? Usually, we tend to explain this in a non-phenomenological way, by treating the thing we want to explain as something that is independent from our perspective. We might say that the difference is due to a difference in tempo, or that the first one is very spacious while the second one is filled with sounds. This is all very true of course, I cannot argue with it. But, according to phenomenologists it is not the root cause of the difference between the two songs. Whereas a non-phenomenological perspective treats the things we want to describe as independent entities, phenomenologists treat them as, well, phenomena, which is the experience itself directly as we experience it without even reflecting on it. And, according to phenomenologists, this direct experience is the root of everything we know and understand about the world, which means that it is the root cause, i.e. it grounds the difference between both songs.

So, what is this world of phenomena then? Importantly, it is determined by an interaction between the knower and what is known, as phenomena do not exist independently. Husserl would say that the relationship is one of intentionality. We direct our attention, our consciousness, to something around us, and thereby ‘open’ up an experience. This was the case when you listened to both songs: by engaging with the songs, you experienced the music in a certain way. Just like we cannot verify that we have the same experience of a color when we look at a green apple, it is very hard to describe what the experience you just had amounts to. This is recognized by phenomenologists, because the main function of language is to describe the world as independent objects that we think about in a reflective state. But if we want to describe phenomena, we want to describe them as we experience them before we think about them as independent objects, since we experience them directly. Therefore, Husserl introduces the concept ‘epoché‘, which we have to perform on ourselves if we want to discover the phenomenological world of intentional relations. It means that we have to temporarily forget what we normally think and know about the world if we want to reflect on it as a world that exists independently from our cognition. This might seem abstract, but we did precisely this when we put aside our knowledge of music when we analyzed how we experienced both songs. Just focus on the direct experience as it is experienced, forget everything else. Phenomenon and intentionality might seem a bit too abstract to grasp now, but I will explain this in more detail right after using another experiment.

Philosophical exercise 1

Perform the epoché on yourself and then listen to the songs again. Can you give a description of the direct phenomenological experience? Is it different from the one you made initially?

In any case, music is just a way for me to leave the world of independence, of objects, behind in order to enter the world of intentional phenomena. We are here to discuss climate change. In this chapter, I want to explain how the originator of the phenomenological method, Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) regarded knowledge as a phenomenon, and apply that to how we know climate change. Ideally, we want to work together towards a common goal regarding climate change, whatever it might be. We therefore have to convince one another that one approach would be best. At first sight, argumentative analysis seems like the best solution: if we can think clearly and openly, we should agree if the facts are the same. But, this is a non-phenomenological approach, which I therefore want to avoid. In this chapter, I will therefore explain how we can understand our knowledge of climate change as a phenomenon.

Knowledge as Fulfillment

With a grasp of phenomena in general, we now move to knowledge as a phenomenon. Let us do another real life experiment; phenomenology was Husserl’s attempt to make philosophy scientific after all. Let us drop a pen on the ground. Do you have one nearby? Do not worry if there is not a pen around, any other object with weight will do. Fortunately for us a lot of objects have weight.

Ready? One, two, go!

…

Okay? Okay.

Let us scientifically evaluate what happened. When you dropped the pen, it fell to the ground and stayed there. How come? Again, we have some nice theories in physics for why that happened. The big mass of earth attracted the pen towards its center, but the rigidity of the ground and the pen prevented it from going through it. Case closed, no need for any strange philosophical theories it seems. What more is there to know? Well, much more, according to Husserl. The explanation we just gave comes from what he calls ‘the natural attitude’ (Ideas, §§27, 31, & 47). This is the non-phenomenological point of view we ordinarily have in the world, based on which we explain stuff. It is the common standpoint before we perform the epoché on ourselves. According to Husserl and me, it (wrongly) assumes two things:

- The world exists independently from our cognition.

- Hidden behind the independently existing world are some fundamental laws and/or structures that shape it, which are not observable to us.

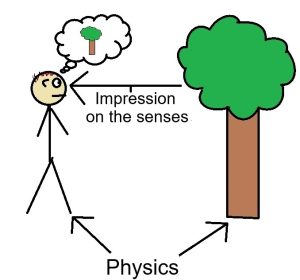

In our evaluation, we mistakenly assumed that some independently existing pen and ground were moved by some independent, hidden, and within our grasp of knowledge quite mysterious forces of physics. However, and now comes the most controversial claim of this chapter: not physics but phenomenology is fundamental. This means that fundamentally, the experiment should be described phenomenologically, as a relation of intentionality between the subject and the object. Phenomena are our entrance into the world that we know, all other knowledge is based on this. The initial evaluation using physics and chemistry is not wrong per se, as it is true according to its own methodology. But, it is grounded in phenomenological knowledge. Furthermore, because phenomenology is the fundamental science, the initial non-phenomenological evaluation itself can also be analyzed using the phenomenological method in order to reveal its most fundamental nature. In fact, everything can be analyzed phenomenologically in order to reveal its most fundamental nature – which is what Husserl tried to do during his lifetime. We can therefore also analyze our knowledge of climate change using the method of phenomenology, in order to hopefully improve cooperation.

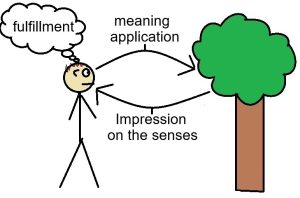

But before I move on towards the phenomenology of scientific knowledge, I will first try to make the position of phenomenology more attractive. Why should phenomena, and not the independent world be fundamental? One important aspect that both phenomenology and the natural attitude share, is their assumption that all knowledge is grounded in what we observe. For the natural attitude the independent world is observed by us, and therefore we know what is out there. When I see a pen, it reflects light, which enters my eye, and therefore I see it. All these processes happen independently of my consciousness. However, seeing a pen is different in phenomenology. When I look at the pen, my consciousness focuses on it, and automatically applies meaning to the object I observe. I see a pen, which is something different than reflected photons. There is an idea of ‘pen’, which I already apply to the object by seeing it, and therefore I know it as a pen. Now, if you say that the photons are primary, and not the applied meaning of ‘pen’, I ask: how can we know for sure that photons are the fundamental explanation, and not only some idea we created based on experiments? Is there not some other fundamental theory that explains photons, which would mean that they are only an idea in our minds and not something that exists outside of us? Can we ever be sure that one theory of physics is the most fundamental? No, we simply cannot. What I know with complete certainty when I look at a pen is that I am seeing that pen. Scientific theories are then created by us to explain those certainties, being intrinsically uncertain themselves. To me, it is obvious that this must imply that phenomena are primary, and that the natural attitude is not sound. As a big bonus, we avoid skepticism by accepting a world that is undeniably true.

What is knowledge then, phenomenologically? Well, Husserl describes this as fulfillment (Logical Investigations, VI §8). Before I observe something, before the intentional relation exists between me and an object, I already expect certain things to happen based on earlier experiences. For Husserl, experiencing the world is a constant flow of given meanings with expectations and their realizations of what was expected, of what I already know of the world. For example, if I look at a pen, I can only see one side, but based on earlier experiences I already expect the other side to look a certain way. My expectation unconsciously fills in the missing pieces. Therefore, the pen is already given to me in experience as a complete three dimensional object, based on a synchronization of what I observe directly and what I expect the thing to be. In other words, the phenomenon I observe is the result of what I see directly and the meaning I apply to what I see. The relation of intentionality flows in two directions: from subject to object and object to subject. Fulfillment then, is when the meaning I apply to what I observe matches that. When both are synchronized. Interestingly, this relates to ‘knowledge by acquaintance’ as explained by Anita Spanjer in the previous chapter. Knowledge by description alone does not count as fulfillment, we need to be acquainted with the consciously-experienced phenomenon. Consciously or unconsciously, Husserl thought we get a feeling that the information just makes sense: ‘what I understand is clear, I can grasp it well when I think about it’. A good thing about phenomenology is that I do not have to argue a lot in order to get my point across. Phenomenology is more about semantics than rational arguments. Everyone can verify this description by analyzing their own direct experience of knowledge.

Philosophical excercise 2

Try to think of something you learned last week, then apply the epoché to yourself again. Does the direct experience of the moment you learned it come down to Husserl’s description of knowledge?

For our use, there are two main groups of fulfillment according to Husserl: sensible and categorical (Cartesian Meditations, §6). The former has to do with what we observe directly, the world around us as we experience it in a constant flow. The latter is more abstract; it concerns theories our rationality creates in order to explain how everything works. All scientific knowledge falls under the latter, for example. Using scientific methodologies, we can verify whether they correspond to what we experience, and if that is not the case, we can change them for the better. Hence, climate change models should be regarded as part of the group of categorical knowledge, as obviously, we cannot experience such models directly, or else we would have always already known their validity.

Knowledge of Climate Change

Based on this understanding of knowledge as fulfillment, I have created three conditions for knowing that human-made climate change is true. If all three conditions are met, we should be able to explain changes in weather patterns using climate change.

Three Conditions in Order to Know Climate Change

- We have to know through experience that weather patterns are changing.

- We have to have an expectation that this is due to human-made climate change.

- These two have to be synchronized in our experience, so that the knowledge makes sense.

The first condition relates to the data our senses pick up, which has to fit the meaning we apply to it. As we can only directly experience weather patterns, and we want to explain that the climate is changing, we have to experience changing weather patterns. The second condition relates to the meaning that we apply to the data. The third condition relates to the possibility of synchronization; if they cannot be synchronized, fulfillment cannot take place.

Can all conditions be met? It is easy to satisfy the first one. The weather is an easy talking point because we all experience it. Depending on where we live, we probably experience it changing to some degree compared to previous decades. The third condition is also easy to meet in my opinion. Climate change is a proper explanation of changing weather patterns; to the people who employ this explanation, it makes sense. If this was not the case, hardly anyone could be convinced of its validity. However, the problem lies in the second condition. Even though human-made climate change is a model that gives meaning to changing weather patterns in a way that makes sense, a climate model cannot be experienced directly. Due to its intellectual nature, different explanations could easily be applied. Maybe it is due to more activity from the sun. Maybe it is due to the gods being angry with us. This is because it is different from sensory knowledge. I know what the backside of a pen looks like because I have seen the other side before. The expectation and meaning I apply to the sensory data stem from information I directly perceived earlier. Categorical knowledge, however, is a scientific achievement. Its explanations should be tested scientifically in order to convince those who test it that the weather patterns change due to this.

Thankfully, what we have learned can provide the solution. If we take a more bird’s-eye view of the three conditions, it becomes clear that Husserl has a very rational description of human categorical knowledge. If we have a certain explanation, and if new evidence we understand points to a different direction, the older explanation becomes different: one that no longer makes sense to us. In other words, the intentional structure between the subject and that phenomena we want to explain changes. Now, we can disagree with this because humans sometimes come up with irrational explanations, when we are hallucinating for example. However, for a hallucinating person, the same structure of fulfillment still applies: it is shaped by cognitions that are not shared by other persons. A hallucinating person, according to Husserl, still rationally tries to choose the best explanation of phenomena, because our cognition fundamentally works that way.

The solution I propose, therefore, is to treat each other as rational beings that try to explain the changing weather patterns the best they can, by giving them insight

into what the best explanation is. Humans are rational beings in the end, who need and want to have the best meaning available to explain the experienced world around us. This means that we should not try to convince each other for the sake of convincing like in a debate, but really to give each other insight into the meaning of the description, so that it serves as a proper explanation of experienced phenomena for that person. With this, the meaning they apply to the data they receive is synchronized in a way that makes the most sense for them. For example, when the weather gets wetter every year with more storms occurring in a certain location, explain climate change in such a way to inhabitants of that place so that it is the best explanation they have for the changing weather patterns. What part of the model explains those patterns, and why is the model itself better than other explanations? Do not treat it like a game of fallacies, do not treat other people like irrational believers of nonsense. Treat them like people who want to understand it the best they can, and help them do this.

References

Husserl, Edmund. 1960. Cartesian Meditations. Trans. Dorion Cairnes. The Hague:

Martinus Nijhoff.

Husserl, Edmund. 1970. Logical Investigations. Trans. John N. Findlay. New York:

Humanities Press

Husserl, Edmund. 1983. Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a

Phenomenological Philosophy. Book I. Trans. Fred Kersten. The Hague: Kluwer

Academic Publishers.