Introduction

Jeroen Bos

Background: a closer look at Joan Blaeu’s Atlas Maior

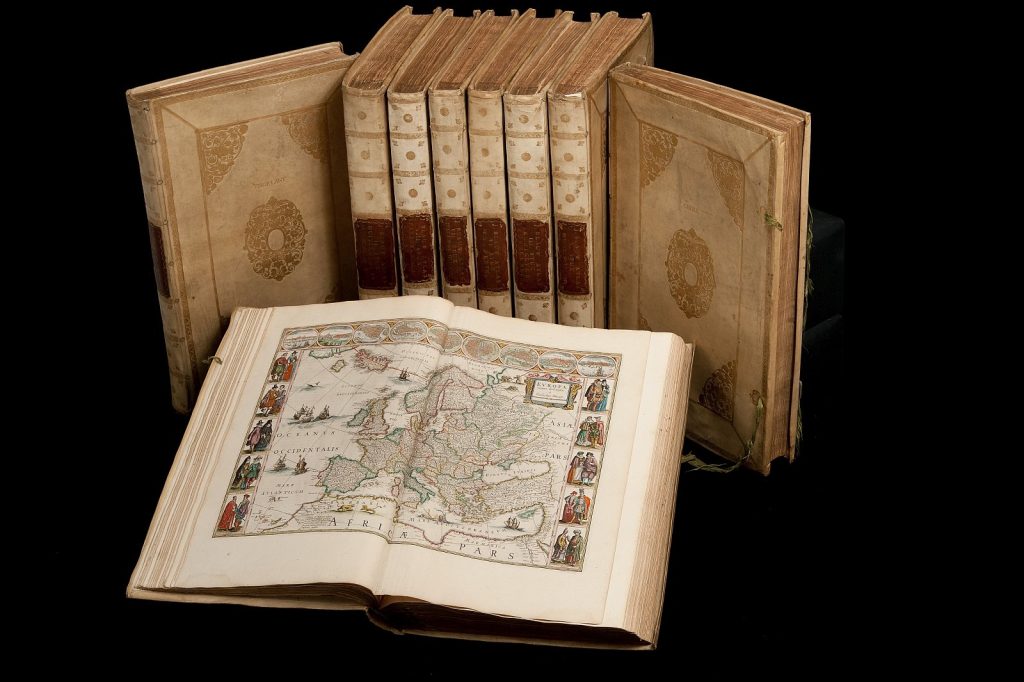

There is no time like the present for a thorough analysis of seventeenth-century Dutch publisher Joan Blaeu’s Atlas Maior. Why, you ask? Is this publication not one of the best-known world atlases ever to have been produced? The book is internationally acclaimed as the most splendid example of seventeenth-century Dutch cartography. Blaeu’s individual maps are highly sought after by collectors to this day. In late 2015, an intact and well-preserved atlas was auctioned off for a record amount of €831,000.

Ever since its publication, the Atlas Maior has been considered extremely valuable and it has certainly been studied extensively over the past decades, with historical cartographers focusing on its 594 maps in particular. But the accompanying texts have been examined much less closely so far. It seems logical that the maps were what attracted researchers. That is what an atlas is after all: an orderly collection of maps. But – following other publishers of cartography – Blaeu also added pages and pages of text to his maps. The Dutch edition of Atlas Maior, which was published as Grooten Atlas, comes with nearly 4,000 pages of text. The French edition, entitled Le grand atlas ou Cosmographie blaviane, has as many as 5,300 pages.

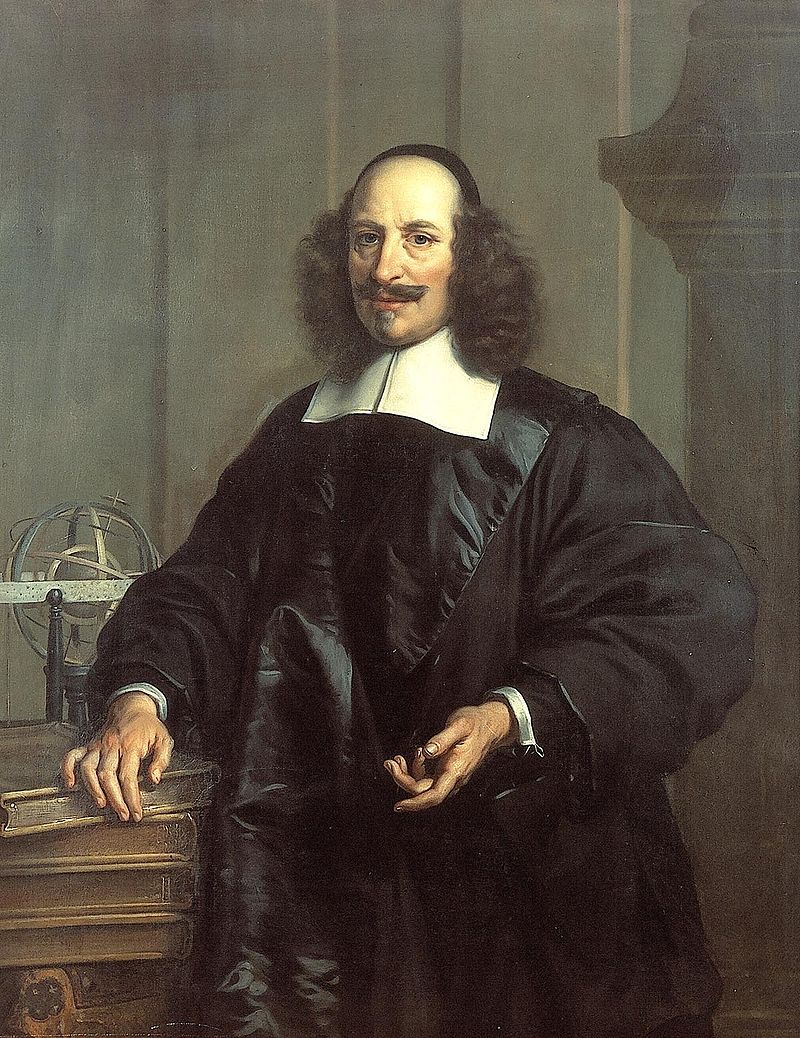

Willem Jansz. Blaeu (1571-1638), founder of the printing company, publishing house, and bookshop, and his son Joan Blaeu (1598-1673) lived in the Dutch Golden Age. It was during this period of about a century that the Dutch Republic took shape, declared independence from Habsburg Spain, and became a colonial superpower in its own right. From far and wide, ships flocked to Amsterdam in particular, which had established itself as an international staple port. It was in Amsterdam, at the street that is now known as Damrak, that Blaeu ran his shop. The ships arriving at the port brought in the information from overseas; it was simply flowing into the shop, as it were.

Joan Blaeu around 1660 as portrayed by Jan van Rossum (image: Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed)

European readers were keen to learn about other countries and foreign peoples. The travel journals of European explorers and merchants were much in demand. They were printed, reprinted, and translated. Publishers had a tendency to somewhat embellish eyewitness accounts, trying to create a connection with knowledge from classical Antiquity or the Middle Ages. Another factor was the authority of the Bible, especially where regions mentioned in biblical narratives, such as Palestine or Egypt, were concerned.

These were the information sources – travel journals, knowledge from classical Antiquity, and the Bible – that were available to Blaeu as inspiration for his texts. Or rather, to the editors who wrote the texts for him. Just like Blaeu did not personally engrave the maps, it is improbable that he wrote all 4,000 pages himself. While he will undoubtedly have performed spot checks of the texts before signing off on them to protect his reputation, Blaeu only supervised the writing process.

Academic and societal relevance

So, as we have established, it is high time for a critical analysis of Blaeu’s texts and descriptions. But where to start? As part of the 2023/2024 seminar Beyond the Map: Descriptions of the non-European World in Joan Blaeu’s Atlas Maior, we selected twenty non-European regions from the Atlas whose descriptions (in Dutch) were studied by students of History. An analysis of the texts in Blaeu’s Atlas has academic as well as societal relevance. As mentioned, in the past, researchers of Blaeu’s Atlas and its production process focused mainly on the maps. By performing an in-depth analysis of the accompanying texts, we can learn more about how early-modern Europeans wrote about non-European countries and peoples. It is important to remember in this context that Blaeu was not an original writer. Rather, he selected his texts from other sources. This is where the academic relevance comes in. What sources did Blaeu use? What information did he copy from others and what did he exclude, either intentionally or unintentionally? Dutch historian Djoeke van Netten has posed this question earlier by referring to the role of early-modern publishers, such as Blaeu, whom she calls gatekeepers of knowledge. Van Netten claims that publishers not only served as conduits for new knowledge, but they were also in a position to stop information from being spread, either deliberately or not, and for varying reasons.[1] Another question that was posed in the seminar: what are Blaeu’s descriptions of indigenous peoples like? Are they positive, negative, or neutral in tone? And as a follow-up: what might be the reasons for these positive, negative, or neutral connotations? And finally: did Blaeu’s descriptions contribute to the stereotyping of indigenous peoples by the end of the seventeenth century, and does this stereotyping still affect the way we look at them today?

You might wonder: why Blaeu? He was not an original writer. He selected his texts from other sources and chose to copy them. Also, you would be right to ask how much authority and weight Blaeu’s texts actually had. Whatever the language edition, the volumes of Atlas Maior are generally ‘clean’ — meaning that they are without annotations by previous owners. The volumes were mostly intended for display by its wealthy owners, not for rigorous reading and studying. Despite this, because of its sheer size and iconic status, Blaeu’s Atlas Maior lends itself perfectly to answering these questions.

His selection of older and contemporary sources allows us to find out which information about non-European regions and peoples publishers (such as Blaeu) wanted to impart to their readers. Frequent repetition of texts lends them weight (authority) and will eventually put them at the centre of the discourse. In his ground-breaking book Orientalism (1978), academic and literary critic Edward W. Said opened our eyes to the depiction and portrayal of ‘the Other’ by Europeans since the nineteenth century.[2] European authors were less concerned with accurately describing the locality and history of the indigenous peoples and more with the power dynamics involved in creating and controlling knowledge about local cultures. They engaged in cultural recipience, reshaping the local landscape to mirror their own and appropriating and reinterpreting knowledge and cultures to fit European intellectual frameworks. Their representations of the Other (i.e. non-European) were so distorted that the local population barely recognized themselves, if at all. In his book, Said limits his post-colonial criticism in chronological terms to a discussion of the European discourse since the early-nineteenth century; in geographical terms, he focuses on the relationship between Europe and the region that is referred to in the Western world as the Near East or the Middle East.

It was historian Benjamin Schmidt who, in his book Inventing Exoticism: Geography, Globalism, and Europe’s Early Modern World (2015), connected Said’s theories with early-modern cartography and other disciplines. Schmidt argues that modern critiques of the colonial discourse of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, such as Edward Said’s, assume the presence of this discourse, but do not address the origins of this ‘production of colonial knowledge’ in the early-modern world and the role of Dutch printers and publishers in this in particular.[3] With their cartographic productions, they painted a picture of the world that was pleasantly exotic and utterly familiar at the same time. The Dutch publishers had a pan-European audience of readers, which explains why it was easy for them to publish atlases with the same map imageries in different European languages.

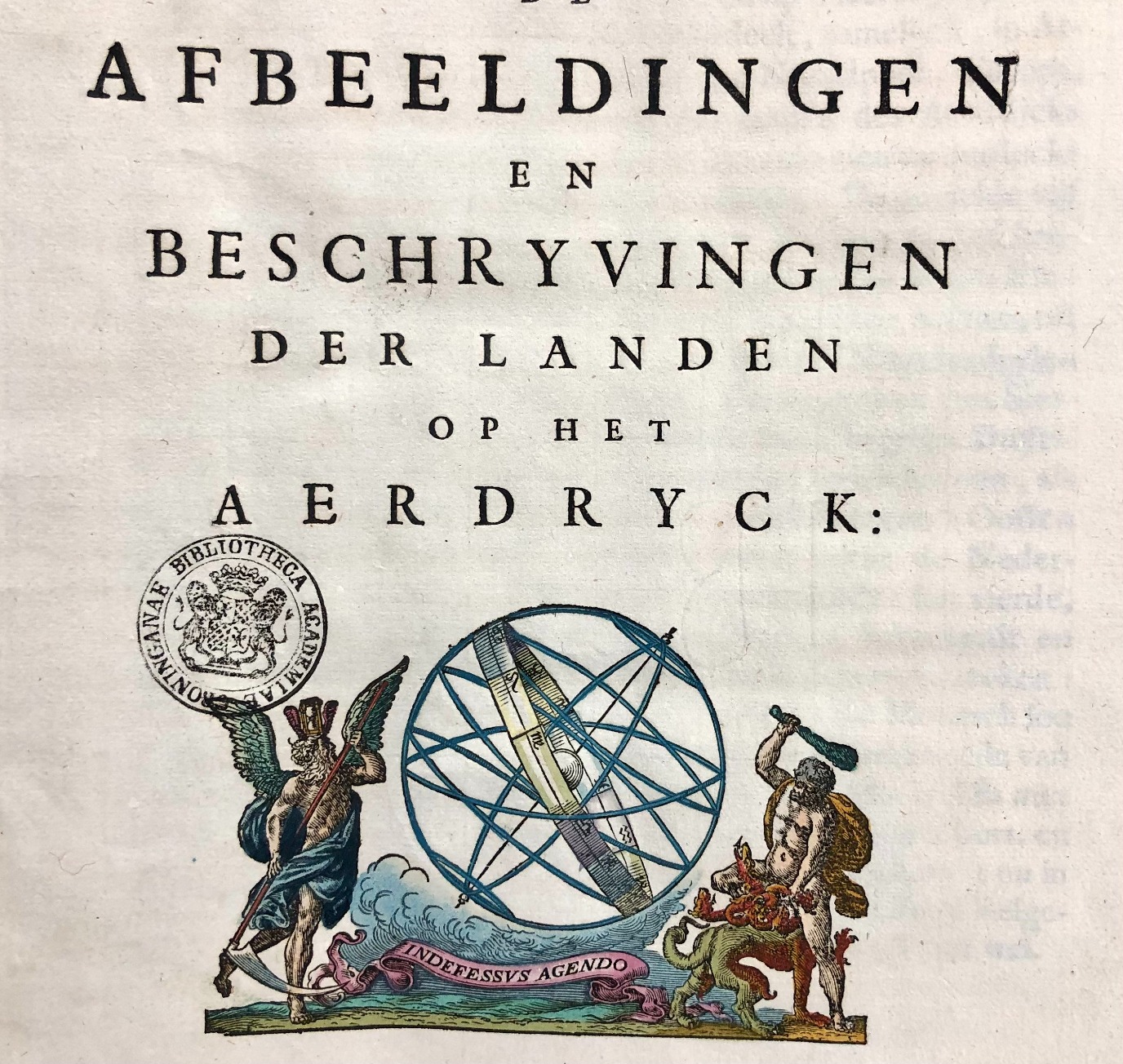

Blaeu’s title page already announces that his Atlas contains both maps and textual descriptions.

And then for the texts. ‘Words matter.’ With this truism, Wayne Modest, Director of Content of Wereldmuseum and Professor of Material Culture and Critical Heritage Studies at VU Amsterdam, encourages researchers, and students primarily, to ask themselves how the historical narrative can be written such that it does justice to the victims of colonialism. In the recently published research guide Nederlands kolonialisme van archief tot geschiedschrijving [Dutch Colonialism from Archives to Historiography] (2023), Modest argues that people should be aware of loaded language that perpetuates certain power dynamics and implicit biases inherent in colonial history.[4] How to deal with problematic cultural and historical terminology? Take the term ‘Indian’, for example. We all know that this is a highly controversial term, coined by Europeans, used to describe the whole entirety of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. At the same time, the word is virtually irreplaceable since some of those same indigenous peoples have chosen to embrace it as a form of self-identification. Modest urges us to take a long and hard look at the origins and contemporary usages of words, with the aim of ‘creating an equal and just world’.

Modest’s plea was reflected in the Jansonius Lecture 2024, which was delivered by Margriet Hoogvliet, professor at the University of Amsterdam. In her lecture, Hoogvliet addressed another current topic: national pride. Using texts about, and maps of, Africa, the Americas, and Asia in Blaeu’s Atlas Maior to illustrate her point, Hoogvliet argued that the Dutch ‘can no longer simply claim Dutch cartography from the sixteenth century onwards as part of their proud national heritage; it carries too many negative historical connotations that are impossible to ignore’. [5]Blaeu’s Atlas Maior elicits a sense of national pride in the Netherlands. Testament to this, it has been included in the Canon of the Netherlands, a list of fifty important events or persons that have defined Dutch history. Although the Canon is not part of the required curriculum, it is frequently used as a reference point for teaching history in Dutch primary and secondary schools. Blaeu’s Atlas is referred to as a masterpiece and a splendid accomplishment. That is what generations of pupils are, and have been, told about this piece of Dutch book history. In line with Hoogvliet, we might ask ourselves, however, whether Blaeu’s atlas can truly be considered a splendid accomplishment.

This is what prompted us to perform a thorough text analysis of the descriptions in Atlas Maior and what lends academic and societal relevance to the pioneering work by a group of University of Groningen history students.

Student’s contributions: reader’s guide

In their contributions on the selected regions from Atlas Maior (Dutch edition: Grooten Atlas), the students describe their initial exploratory findings. They studied how the indigenous peoples were described in the Atlas and offer possible explanations for these descriptions, as well as addressing the sources Blaeu used, focusing mainly on how recent – or outdated – they were. As mentioned, Blaeu frequently used outdated information. In each student’s contribution, suggestions are made for further reading, for instance about the region in question or about a larger, overarching theme, such as the way in which non-European indigenous peoples were systematically marginalised in early-modern literature. Each contribution starts with a number, the title of the map, and the title of the text as included in Atlas Maior. The number refers to the nine volumes of C. Koeman’s Atlantes Neerlandici, an authoritative reference work for historical cartographers. The second volume in this series focuses on the folio atlases published by Willem Jansz. Blaeu and Joan Blaeu. The so-called ‘Koeman number’ allows you to easily locate the correct historical map. The title of the map should also help to find it, although it should be noted in this context that competing publishers tended to use the same map titles. In other words, the titles as such are not unique to the maps in Atlas Maior. The titles of the contributions will point you in the right direction as far as locating the relevant passages in the volumes of Atlas Maior are concerned. We have not used any page or folio references, since these may show (slight) differences in collation.

Digital exhibition

This open textbook is a derivative of the digital exhibition of the same name, which was set up in collaboration with the Special Collections of the University of Groningen Library. As part of the seminar, the students wrote a short public text of approximately 450 words about the region they were studying. During the completion of this exhibition, the idea arose to also offer the texts and images in this form, as an open textbook. The texts have been reused in unchanged form. Thanks go out to the group of students whose contributions we were allowed to reuse for this publication. Our thanks also go out to the Special Collections department for reusing the epilogue, written by Adrie van der Laan and Evert Jan Reker, and for reusing the digital images that were made of the Grooten Atlas and other primary publications.

Browsing through Atlas Maior (Grooten Atlas) yourself

Atlas Maior, the nine volumes of the Dutch language edition of Atlas Maior (in Dutch: Grooten Atlas). Image: Utrecht University

Digital version

Literature

Much has been written in recent decades about the cartography, the publishing practice and the (inter)national network of the Blaeu firm. Here we only provide a brief overview of current and relevant literature, in English and Dutch, about (the larger world of) Blaeu.

Boogaart, E. van den (2019). Vreemde verwanten: de wereld buiten Europa 1400-1600. Nijmegen: Vantilt.

Koeman, C., & Krogt, P. van der (2000). Koeman’s Atlantes neerlandici / Vol. 2, The folio atlases published by Willem Jansz. Blaeu and Joan Blaeu. Houten: HES & De Graaf.

Krogt, P. van der (2005). Joan Blaeu, Atlas maior of 1665. Köln: Taschen.

Netten, D. van (2012). Koopman in kennis: de uitgever Willem Jansz Blaeu (1571-1638) in de geleerde wereld van zijn tijd. Zutphen: Walburg Pers.

Said, E.W. (1978). Orientalism. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Schrikker, A., (red.). (2023). Nederlands kolonialisme van archief tot geschiedschrijving: een gids voor onderzoekers. Leiden: LUP.

Schmidt, B. (2015). Inventing exoticism: geography, globalism, and Europe’s early modern world. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Vannieuwenhuyze, B., (red.). (2023). Oude kaarten lezen: handboek voor historische cartografie. Zwolle: WBOOKS.

Wolf, E.R. (1982). Europe and the people without history. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Zandvliet, K. (2023). De wereld van de familie Blaeu. Zutphen: Walburg Pers.

- Netten, D. van (2012). Koopman in kennis: de uitgever Willem Jansz Blaeu (1571-1638) in de geleerde wereld van zijn tijd. Zutphen: Walburg Pers. ↵

- Said, E.W. (1978). Orientalism. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ↵

- Schmidt, B. (2015). Inventing exoticism: geography, globalism, and Europe's early modern world. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ↵

- Schrikker, A., (red.). (2023). Nederlands kolonialisme van archief tot geschiedschrijving: een gids voor onderzoekers. Leiden: LUP. ↵

- Cited from the announcement [in Dutch] of the Jansonius Lecture 2024 ↵