Peru

Jorik Davids

This contribution is published in both Dutch and English. You will find the English version below.

| Nummer Koeman’s Atlantes Neerlandici, vol. II | 9820:2.2 |

| Titel kaart / Titel tekst | PERV / Perv |

De Grooten Atlas, een fascinerend werk gemaakt door cartograaf en uitgever Joan Blaeu, toont meer dan alleen prachtige versierde kaarten. De aanvullende informatie naast deze kaarten onthult ook hoe tijdgenoten van Blaeu keken naar de grote mysterieuze wereld.

Deze tekst richt zich in het bijzonder op de wijze waarop Blaeu de regio’s van Chili en Peru omschreef. De regio’s Chili en Peru in de Grooten Atlas omvatten het huidige Noord-Chili, Peru, Ecuador en gedeelten van Bolivia en Colombia. Hieronder vallen de oorspronkelijke leefgebieden van de Inca’s en vele andere volkeren, zoals de Araukaners (Mapuche) en de Aymara.

Blaeu gebruikt herhaaldelijk de categorie “indianen” om te verwijzen naar de oorspronkelijke bevolking van Chili en Peru. Dit is een term die is blijven hangen als gevolg van de misvatting van Columbus dat hij India had bereikt. Het lijkt erop dat alleen de Inca’s, alhoewel zij ook werden gezien als “indianen”, genoeg respect of verwondering hadden opgewekt om genoemd te worden bij een specifieke volksnaam. De andere oorspronkelijke bewoners kregen simpelweg het label “indiaan” opgeplakt. Positieve opmerkingen over deze oorspronkelijke bewoners zijn zeldzaam in de teksten van Blaeu, maar zijn wel te vinden in de beschrijvingen van de Inca’s. Opmerkingen over de andere “indianen” richten zich grotendeels naar het contemporaine perspectief dat vooral (op een negatieve wijze) de verschillen benadrukte.

Ondanks het feit dat de Spanjaarden in hun exploitatiesysteem gebruikmaakten van de oorspronkelijke bewoners als goedkope arbeidskrachten, ontbreekt in Blaeu’s teksten een vermelding naar een belangrijke groep die eveneens aanwezig was, maar niet genoemd wordt. Namelijk de tot slaaf gemaakte mensen uit Afrika, die via de Atlantische Oceaan naar Zuid-Amerika waren gebracht. Na de afschaffing van de slavernij op de oorspronkelijke “indianen” in 1542 was deze groep in grote aantallen aangevoerd om dwangarbeid te leveren.

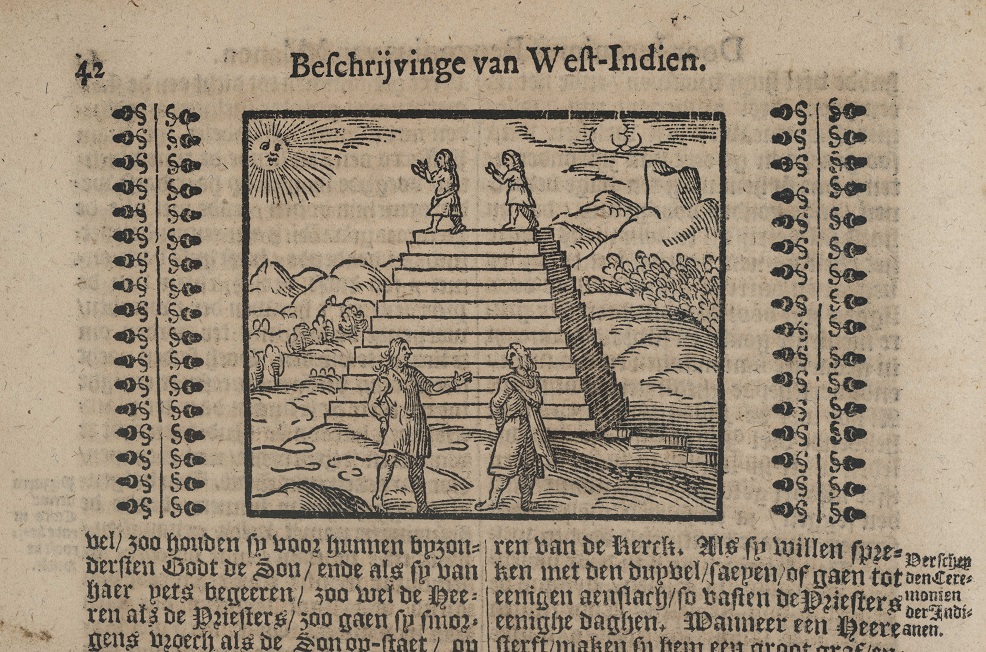

Girolamo Benzoni, Beschryvinghe van West-Indien, waer in verhaelt wordt, de eerste vindingh van de eylanden, steeden, plaetsen, en rivieren (Amsterdam: Gillis Joosten Saeghman, between 1661 and 1666), p. 42: “The way in which the Indians of Peru worship the Sun.”

Alhoewel de Nederlanders geen kolonie hadden in deze regio, komen zij toch een paar keer voor in de teksten van Blaeu. In de eerste helft van de zeventiende eeuw waren zij namelijk, vanuit hun basis in Mauritsstad (Recife), actief in het plunderen van de Spaanse koloniën. Opmerkelijk is dat de grootschalige poging van de West-Indische Compagnie (WIC) om via de Chili-expeditie van 1643 een eigen kolonie te stichten in dit gebied onvermeld blijft. Vermoedelijk was dit een bewuste keuze van Blaeu, om zo de lezer niet verder te belasten met het collectief Nederlands trauma dat deze mislukte expeditie teweeg had gebracht.

Blaeu noemt voornamelijk de verdiensten van de Spanjaarden in de regio’s. Hij schetst een haast romantisch beeld van de rijkdommen die de landen te bieden hadden, maar benoemt vrijwel niet dat de wijze waarop Spanje haar dominantie had verkregen met veel bloedvergieten gepaard was gegaan. Er klinkt haast een natuurlijke vanzelfsprekendheid van de Spaanse (of breder: de Europese) suprematie in de beschrijvingen van Blaeu.

Suggestie om verder te lezen:

Henk den Heijer (2015). Goud en Indianen – Het journaal van Hendrick Brouwers expeditie naar Chili in 1643. Zutphen: Walburg Pers.

| Koeman’s Atlantes Neerlandici, vol. II | 9820:2.2 |

| Title map / Title text | PERV / Perv |

The Atlas Maior, a fascinating work by cartographer and publisher Joan Blaeu, is more than a set of elaborately decorated maps. The descriptions accompanying these maps are a reflection of how Blaeu and his contemporaries viewed the large, mysterious world.

Blaeu’s description of the region of Chile and Peru encompasses modern-day northern Chile, Peru, Ecuador, and parts of Bolivia and Colombia. This is where the Incas and many other indigenous peoples, such as the Araucanians (Mapuche) and the Aymara, lived.

Blaeu repeatedly uses the term ‘Indians’ to refer to the indigenous population of Chile and Peru, a persistent term originating from Christopher Columbus’s mistaken belief that he had reached the subcontinent of India. Although the Incas were also regarded as ‘Indians’, it seems that they were the only people who had commanded enough respect or wonderment to be called by a specific name. The other indigenous peoples were simply labelled as ‘Indians’. Blaeu has few positive things to say about these indigenous peoples in his descriptions, but he does praise the Incas. Comments about the other ‘Indians’ mostly stress the contemporary perspective that they were different from Europeans — in a negative way.

Despite the fact that the Spanish, in their system of exploitation, made use of the indigenous population as cheap labour, Blaeu does not refer to the presence of another important group of people: enslaved workers from Africa, who had been transported to South America via the Transatlantic Trade Route. After the enslavement of indigenous peoples was prohibited in 1542, African slaves were increasingly being imported and subjected to forced labour.

Although the Dutch did not have any colonies in the region, Blaeu does mention them a few times, since they were actively raiding the Spanish colonies from their base in Maurice Town (Recife) in the first half of the seventeenth century. Interestingly, Blaeu does not refer to the Dutch Chile expedition of 1643, a large-scale attempt by the Dutch West-India Company to establish a Dutch colony in the region. This was probably deliberate on the part of Blaeu; he did not want to remind the reader of the collective Dutch trauma that this failed expedition had caused.

Blaeu mainly references the Spanish accomplishments in the region. He paints an almost romantic picture of the local riches, but leaves mostly unsaid that the Spanish dominance was the result of much bloodshed. In his descriptions, Blaeu talks about the Spanish (i.e. European) supremacy almost as a matter of course.

Further reading:

Henk den Heijer (2015). Goud en Indianen – Het journaal van Hendrick Brouwers expeditie naar Chili in 1643. Zutphen: Walburg Pers.