Guyana’s

Sam Beereboom

This contribution is published in both Dutch and English. You will find the English version below.

| Nummer Koeman’s Atlantes Neerlandici, vol. II | 9840:2:2 |

| Titel kaart / Titel tekst | GVIANA SIVE AMAZONVM REGIO / Gvaiana, Oft De Wilde Kvst |

De regio Guiana (de Wilde Kust) beslaat het gebied tussen de rivieren Orinoco en Amazone. De regio Brasil beslaat (gedeeltelijk) het huidige Brazilië.

In de teksten uit de Grooten Atlas over deze gebieden is er sprake van een schijnbare tegenstelling. Enerzijds was er een sterke bewondering voor de “schatten” van de exotische gebieden in Amerika. Zo refereert Blaeu in de tekst naar de mythe van El Dorado: de Vergulde Man. De Spanjaarden geloofden dat een “indiaanse” hoofdman, bedekt met goud, werd ingewijd in een meer dat men in deze regio situeerde. Verschillende expedities werden begin zestiende eeuw opgezet om hem te vinden, waarbij de mythe uitgroeide van een man tot een stad, een land, en ten slotte een koninkrijk van goud. Tastbaardere, aardsere “schatten” zoals maïs, tarwe, peper en vruchten waren zeer gewild. Blaeu schrijft dat er in de regio nuttige geneesmiddelen voorhanden waren: “’t Sap van het blad genaemt Icari, is goedt tegen de pijn in ’t hooft.”

Aan de andere kant wordt (de leefstijl van) de oorspronkelijke bevolking van de gebieden – vanuit een westers perspectief – afgekeurd. Blaeu benoemt dat de mensen veelal naakt lopen, geen religie aanhangen en mensenvlees eten. Ook beeldde hij op zijn wereldkaart uit 1648 kannibalen af in Zuid-Amerika. De beschrijving van de verschillende Zuid-Amerikaanse volkeren door Blaeu komt nauw overeen met de beschrijvingen die Johannes de Laet in 1625 reeds publiceerde. Hoogstwaarschijnlijk is dit de bron voor Blaeu geweest. De Laet beschrijft de volkeren als gewelddadig en zonder enige vorm van beschaving. Doordat dergelijke beschrijvingen in meerdere contemporaine bronnen voorkomen, mag worden aangenomen dat dit de heersende visie representeert.

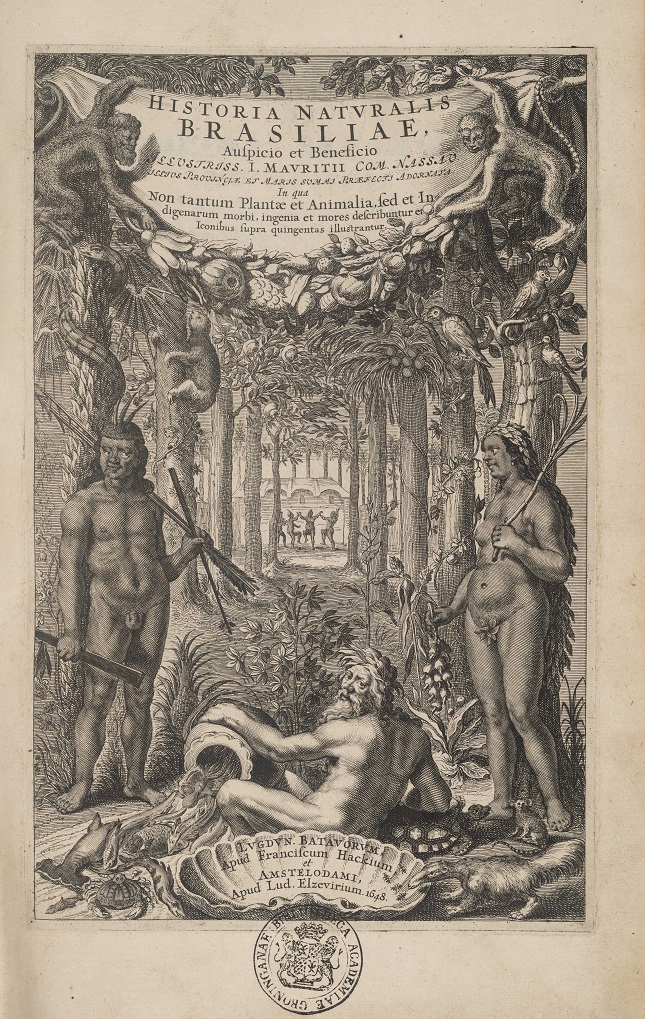

Willem Piso & Georg Markgraf, Historia naturalis Brasiliae (Leiden: Frans Hack and Amsterdam: Lodewijk Elzevier, 1648), title page

De historicus Stephen Snelders schreef in 2012 over de bovengenoemde bewondering voor geneesmiddelen en de Europese visie op Indianen. Hierbij haalt hij Willem Piso (1611-1678), een grondlegger van de tropengeneeskunde, aan. Piso stelde dat de Europeanen ‘natuurlijk’ bepaalden welke geneesmiddelen en -wijzen nuttig waren, aangezien het ging om zaken die hun oorsprong vonden in een ‘barbaarse omgeving’. De kern van de tegenstelling, en de verklaring voor het naast elkaar bestaan van interesse en afgunst, komt daarvandaan. De Europese kolonisten redeneerden namelijk vanuit hun eigen perspectief. Al wat er gevonden werd in de “Nieuwe Wereld”, werd – zowel bewust als onbewust – getoetst aan de Europese norm. Dat wat daarbinnen paste, zoals de benodigde geneesmiddelen om te kunnen overleven in Amerika, werd bewonderd en begeerd. Dat wat daarbuiten viel, zoals de vermeende onbeschaafde levensstijl van de indianen, werd afgekeurd.

De Grooten Atlas van Blaeu is een spiegel van de zeventiende-eeuwse maatschappij waarin Europese suprematie algemeen gedachtegoed werd. De kennis van oorspronkelijke volkeren werd terzijde geschoven, of onbenoemd toegeëigend in wetenschappelijke verhandelingen, zoals die van Piso. De “ander” werd niet ten volle erkend. Deze handelwijze droeg bij aan Westers suprematiedenken, dat deels tot op de dag van vandaag voortduurt.

Suggestie om verder te lezen:

Snelders, S. (2012). Vrijbuiters van de heelkunde: op zoek naar medische kennis in de tropen, 1600-1800. Amsterdam: Atlas.

| Koeman’s Atlantes Neerlandici, vol. II | 9840:2:2 |

| Title map / Title text | GVIANA SIVE AMAZONVM REGIO / Gvaiana, Oft De Wilde Kvst |

Guyana (the Wild Coast) is a region in South America, stretching between the Orinoco and Amazon Rivers. Most of the Brasil region in Blaeu’s Guyana is now part of Brazil.

The texts about these regions accompanying the maps in the Atlas Maior are somewhat paradoxical. On the one hand, the treasures of the exotic regions of the Americas were hugely admired, judging, for instance, from Blaeu’s reference to the myth of El Dorado: the Golden One. The Spanish had heard tales of an ‘Indian’ chief, covered in gold dust, who was christened in a lake they thought was in this region. From the start of the sixteenth century, they started searching extensively for this chief and the myth turned from man into city, into a country, and eventually a kingdom of gold. More tangible ‘treasures’ of the earth, such as corn, wheat, peppers, and fruits were in high demand. Blaeu also writes about useful medicinal herbs: ‘’t Sap van het blad genaemt Icari, is goedt tegen de pijn in ’t hooft’ [the juice of a leaf named Icari helps with headaches].

On the other hand, his European perspective causes him to disapprove of the regions’ indigenous peoples and their lifestyle. Blaeu mentions that they usually go around unclothed, do not have a religion, and eat human flesh. In his 1648 world map, he included an illustration of cannibals in South America. Blaeu’s descriptions of the diverse South American peoples correspond closely to those published by Johannes de Laet in 1625. They most likely served as Blaeu’s source. De Laet describes the indigenous population as violent and without any form of civilization. Given that such descriptions were prevalent in multiple contemporary sources, it is safe to assume that this was the consensus.

In 2012, Dutch historian Stephen Snelders wrote about the Europeans’ admiration for medicinal plant uses in the colonies and their opinion of Indians. In his book, he referred to Willem Piso (1611-1678), a prominent figure in the early history of tropical medicine. Piso argued that ‘of course’ the Europeans were in charge of deciding which medicines and medical practices were useful since the indigenous practices were rooted in a barbaric environment. This is where the crux of the paradox lies; it explains why Europeans were both interested and envious. The European settlers saw things from their own perspective. Anything found in the New World was measured against the European yardstick, both intentionally and unintentionally. Whatever passed the test, such as medicines required to survive in America, was admired and coveted. Whatever did not measure up, such as the alleged uncivilized lifestyle of the Indians, was rejected.

Blaeu’s Atlas Maior is a mirror reflecting the seventeenth-century mindset that Europe was superior to all other parts of the world. The knowledge of indigenous peoples was dismissed or appropriated without crediting its origins in scientific treatises, such as Piso’s. ‘The Other’ was not fully acknowledged. These actions contributed to Eurocentric thinking, which – to some extent – continues to this day.

Further reading:

Snelders, S. (2012). Vrijbuiters van de heelkunde: op zoek naar medische kennis in de tropen, 1600-1800. Amsterdam: Atlas.