Central Asia

Jeroen Bos

This contribution is published in both Dutch and English. You will find the English version below.

| Nummer Koeman’s Atlantes Neerlandici, vol. II | 8050:2 |

| Titel kaart / Titel tekst | TARTARIA SIVE MAGNI CHAMI IMPERIVM / Tartarien Ofte Het Rijck van de Groote Cham |

Tartarije, of het Rijk van de Grote Cham, besloeg in de tijd van Blaeu grote delen van Centraal-Azië en strekte van Turkije tot aan Siberië en China. Duidelijk omkaderd was de regio geenszins. De verwijzing naar de grote khans van weleer, zoals Dzjengis (1162-1227) en Koeblai (1215-1294), doet al vermoeden dat er op oude bronnen wordt teruggevallen.

Het zijn met name de Romein Plinius de Oudere (23-79) en de Venetiaanse reiziger en handelaar Marco Polo (1254-1324) op wie Blaeu leunde. Zo valt er op de kaart bij het fictieve eiland Tazata in de noordelijke ijszee te lezen dat dit eiland door Plinius wordt genoemd. Met uitzondering van het piepkleine ‘Staten Eylant’ linksboven in de kaart (door de Nederlanders vernoemd tijdens de laat-zestiende-eeuwse expedities om de Noord) verwijzen alle steden, streken, meren en rivieren op de kaart naar (verbasterde) namen die Polo noemt in zijn boek Il Milione (Nederlands: De wonderen van de Oriënt).

Plaatsnamen die Blaeu rechtstreeks overneemt uit Polo’s boek vormen bijvoorbeeld het ‘voortreffelijcke Paleys des Grooten Chams Cublai’, gelegen in Ganda, wat het huidige Shangdu (China) is. In de stad Quelinfu (het huidige Jian’ou, tevens in China) vond men volgens de Venetiaan zwarte kippen die ‘hayr als swarte katten’ hadden.

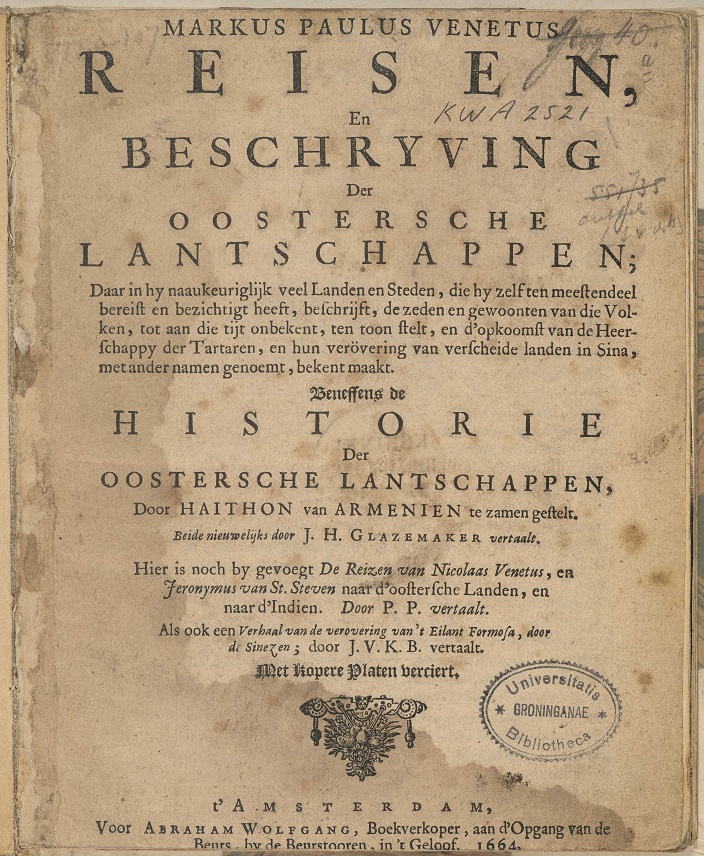

Marco Polo’s travels and descriptions of the lands of the East translated into Dutch by Jan Hendrik Glazemaker, Amsterdam 1664

Hoe wonderlijk deze kippen ook mogen zijn, niets zorgt voor meer verwondering dan de ‘Bonaretz’ (ook: barometz), een fabelwezen dat half plant half dier was. Uit een plant groeide een schaapachtig wezen dat verbonden bleef met de plant. Het voedde zich met gras rondom de plant en als dat op was, stierf het dierlijke gedeelte van de bonaretz. Europese geleerden bleven tot in de negentiende eeuw naar dit fabelwezen zoeken en het opnemen in natuurhistorische publicaties. Toen werd het definitief als fabel bestempeld.

Fabelachtige wezens vinden we ook terug in het kaartbeeld. Zo zijn er bij de regio ‘Desertum Lop’ (een woestijn in de regio Xinjiang) allerlei demonische figuurtjes afgebeeld. Volgens Polo moesten reizende handelaren hier oppassen niet van een groep geïsoleerd te raken. Deze dwalende zielen zouden dan ten prooi vallen aan geesten en demonen, die zich in de woestijn ophielden.

Vraag blijft waarom Blaeu zich op Plinius en Polo baseerde. Was er geen actuelere informatie over de regio voorhanden? Die was er zeker, in gepubliceerde en ongepubliceerde vorm. Het was de Amsterdamse regent en schrijver Nicolaes Witsen (1641-1717) die alle beschikbare informatie over de regio actualiseerde in een veel nauwkeuriger kaart (1690) en het boek Noord en Oost Tartaryen (1705).

Suggestie om verder te lezen:

Peters, M. (2010). ‘Mercator sapiens’ (de wijze koopman): het wereldwijde onderzoek van Nicolaes Witsen (1641-1717), burgemeester en VOC-bewindhebber van Amsterdam. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker

| Koeman’s Atlantes Neerlandici, vol. II | 8050:2 |

| Title map / Title text | TARTARIA SIVE MAGNI CHAMI IMPERIVM / Tartarien Ofte Het Rijck van de Groote Cham |

In Blaeu’s time, Tartary, or the Kingdom of the Great Khan, encompassed large parts of Central Asia, stretching from Turkey to Siberia and China. The region was not at all clearly delineated. Blaeu’s references to the great khans of the past, such as Genghis (1162-1227) and Kublai (1215-1294), give rise to the belief that he relied on old sources, such as Roman author Pliny the Elder (23-79) and Venetian traveller and merchant Marco Polo (1254-1324). The map shows the fictitious island of Tazata in the Arctic Ocean, stating that it was mentioned by Pliny. Except for the tiny ‘Staten Eylant’ (Island of the States General) in the top left corner of the map (named by the Dutch during the late-sixteenth-century Arctic expeditions), all names of towns, areas, lakes, and rivers on the map were copied – some in corrupted form – from Marco Polo’s Il Milione (in English commonly called The Travels of Marco Polo).

Examples of place names Blaeu copied one-on-one from Marco Polo’s book include the ‘voortreffelijcke Paleys des Grooten Chams Cublai’ [magnificent palace of the Great Kublai Khan], located in Ganda, the present-day Shangdu, China. Polo claimed that black chickens with ‘hayr als swarte katten’ [hair like black cats] were roaming around the city of Quelinfu (the current Jianzhou), also in China.

These chickens may have been outlandish, but nothing caused more wonderment than the ‘bonaretz’ (or barometz), a mythical creature that was half plant half animal. It was described as having the appearance of a lamb or sheep growing from the ground. The bonaretz was said to eat the grass and herbs around it; once that was gone, the animal part of it died. European scholars continued to believe in this mythical creature and write about it in natural-history publications as late as into the nineteenth century. After that, the myth was dispelled.

Blaeu also depicted mythical creatures on his map. In the area of the Lop Desert in the Xinjiang region, he drew in a set of demonic figures. Marco Polo claimed that, here, travelling merchants needed to make sure that they were not isolated from their group because, once they were alone, they would fall victim to the spirits and demons of the desert.

The question remains why Blaeu relied on Pliny and Polo. Did he not have access to more up-to-date information about the region? He definitely did, in both published and unpublished form. It was Amsterdam-based statesman and writer Nicolaes Witsen (1641-1717) who updated all available information on the region in a much more detailed map (1690) and in his book Noord en Oost Tartarye [North and East Tartary] (1705).

Further reading:

Peters, M. (2010). ‘Mercator sapiens’ (de wijze koopman): het wereldwijde onderzoek van Nicolaes Witsen (1641-1717), burgemeester en VOC-bewindhebber van Amsterdam. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker