Moluccas

Rozemarie Fokkema

This contribution is published in both Dutch and English. You will find the English version below.

| Nummer Koeman’s Atlantes Neerlandici, vol. II | 8560:2.2 |

| Titel kaart / Titel tekst | MOLUCCÆ INSULÆ CELEBERRIMÆ / Molvccen |

De Molukken beslaan in de Grooten Atlas de eilanden Ternata (Ternate), Tidora (Tidore), Motir (Moti), Machian (Makian) en Bachian (Batjan), gelegen in de huidige Noord-Molukken. Uit de titel van het bijbehorende kaartbeeld, Moluccae insulae celeberrimae (Nederlands: de wereldberoemde Molukse eilanden), blijkt al dat deze relatief kleine eilanden reeds bekend waren in de tijd van Blaeu. Reden voor die “roem” waren de specerijen die hier groeiden, waarvan sommige, zoals de kruidnagel, alleen in dit gedeelte van de wereld voorkwamen. Europese en Aziatische handelaren begeerden een deel in de zeer lucratieve specerijenhandel.

Blaeu schenkt in de regiobeschrijving veel aandacht aan de ‘byzondere’ kruidnagelboom. Kenmerken als waar en wanneer deze groeit, maar ook hoe de kruidnagel geplukt en gedroogd moet worden, krijgen uitvoerige aandacht. Deze aandacht wijst op de beoogde handelsrelevantie van de kruidnagel. De vruchtbaarheid wordt bijvoorbeeld gemeten in commerciële termen. Zo zijn de kruidnagelbomen zo vruchtbaar ‘dat men van eenen twee baren plukt, dat is, 1250 Hollandtsche ponden.’

Daarnaast staat een groot deel van de beschrijving in het teken van concurrerende buitenlandse machten die invloed probeerden te krijgen op de eilanden. Zo geeft Blaeu aan dat Arabische kooplieden al eerder handelden in dit gebied en dat de Molukse bevolking de islam en het Arabische schrift deels van hen hadden overgenomen. Verder leidden de aanwezigheid van Nederlandse, Spaanse en Portugese handelaren op de Molukse eilanden tot conflicten in de late zestiende en zeventiende eeuw. Zij zochten namelijk alle drie naar een monopolie op de specerijenhandel in dit gebied.

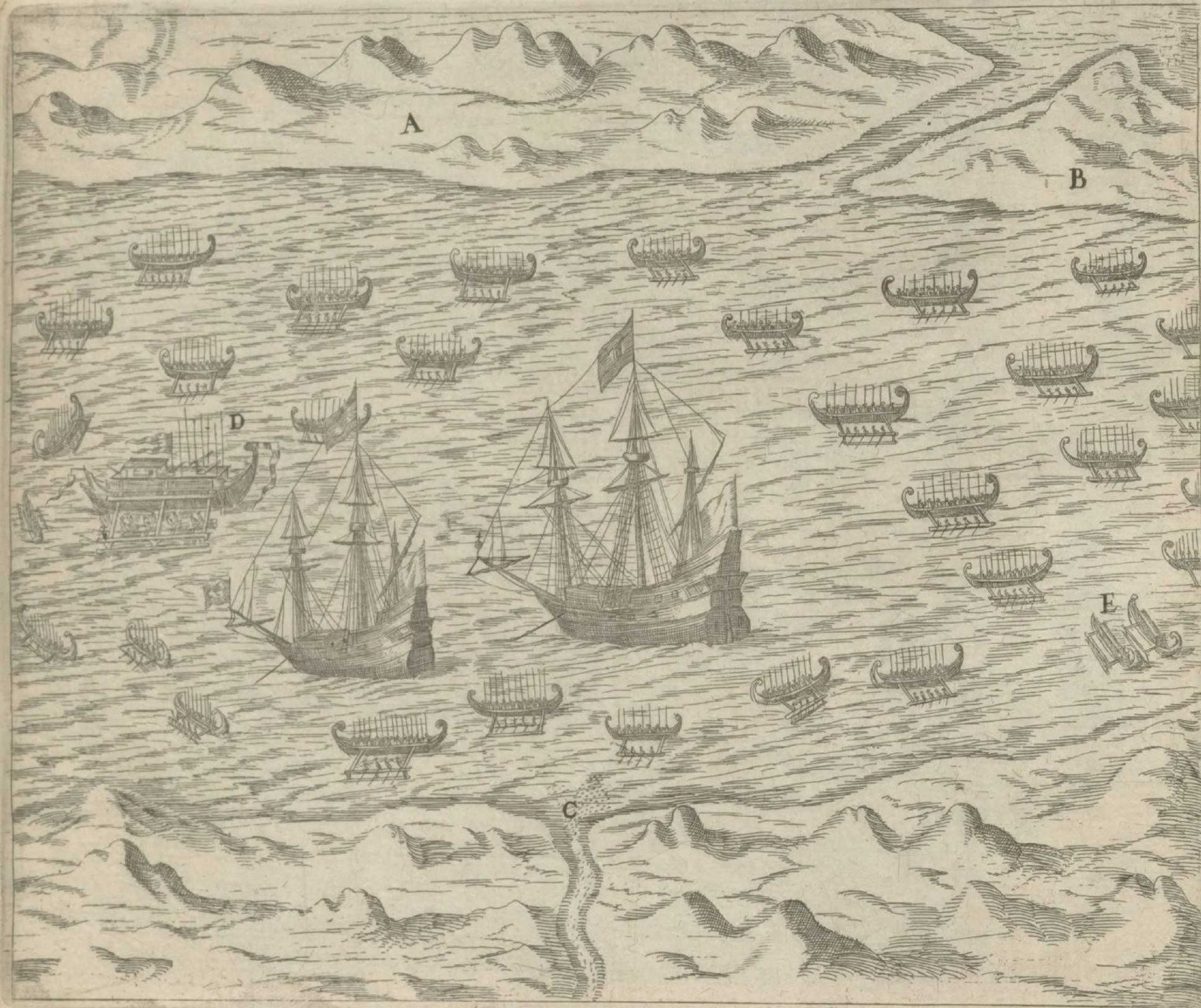

European ships surrounded by Moluccan corcoras off the Tidore coast, in: Quinta Pars Indiae Orientalis (Frankfurt: Matthaeus Becker, 1601), plate XII

European ships surrounded by Moluccan corcoras off the Tidore coast, in: Quinta Pars Indiae Orientalis (Frankfurt: Matthaeus Becker, 1601), plate XII

Zo schrijft Blaeu over het bondgenootschap tussen het eiland Tidora en de Portugezen, en tussen het eiland Ternata en de Nederlanders. Deze buurlanden, volgens de beschrijving ‘soo na by malkanderen, dat men met een grof-geschuts kogel van d’een kust de andere kan bereyken’, waren in constante oorlog met elkaar. Conflicten werden grotendeels uitgevochten op zee, waarin de Molukse bevolking gebruik maakte van zogenaamde corcoras (Kora Kora). Deze traditionele kano’s komen ook voor in het bijbehorende kaartbeeld.

Ten tijde van de publicatie van de atlas (1664) had de Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) de Portugezen en Spanjaarden verdreven en een monopolie op de specerijenhandel weten te krijgen. Informatie over VOC-territoria, zoals de Molukken, was omstreden, omdat hiermee potentiële kennis werd vergeven aan de concurrenten. Belangrijk hierbij te vermelden is het feit dat Joan Blaeu de officiële kaartenmaker van de VOC was, en eigenlijk verplicht tot geheimhouding. Dat maakt de toevoeging van een kaart en beschrijving van de Molukken in de Grooten Atlas zeer opmerkelijk en biedt mogelijkheden tot verder onderzoek.

Suggestie om verder te lezen:

Storms, M. “Geheimhouding bij de VOC? De dubbele petten van Blaeu en van Keulen,” Caert Thresoor, 38(1), pp. 14-25.

| Koeman’s Atlantes Neerlandici, vol. II | 8560:2.2 |

| Title map / Title text | MOLUCCÆ INSULÆ CELEBERRIMÆ / Molvccen |

In Blaeu’s Atlas Maior, the Moluccas encompass the islands Ternata (Ternate), Tidora (Tidore), Motir (Moti), Machian (Makian), and Bachian (Bacan), currently in North Maluku. The Latin title of the map, which is Moluccae insulae celeberrimae [the world-famous islands of the Moluccas], shows that this relatively small archipelago was very well-known as early as in Blaeu’s era. The reason for its ‘fame’ was the presence of spices, some of which, such as clove, were exclusive to this part of the world. European and Asian merchants were very keen to stake their claim on the highly lucrative spice trade.

In his description of the region, Blaeu has much to say about the ‘byzondere’ [special] clove tree. He discusses extensively where clove trees grow, how they are best cultivated, and how cloves should be harvested and dried. This focus points to the relevance of the clove trade. Blaeu measures the productivity of clove trees in monetary terms, saying that they are so productive ‘dat men van eenen twee baren plukt, dat is, 1250 Hollandtsche ponden’ [that one tree will produce two bars, which is 1,250 Dutch pounds].

Blaeu devotes a large section of his description to the fact that competing foreign powers were trying to gain a foothold on the islands. He mentions that Arab merchants were trading in the region earlier and that some of the local population had adopted the Islam religion and Arabic script as a result. In addition, the presence of Dutch, Spanish, and Portuguese merchants in the archipelago led to conflicts in the late-sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries, since they all sought to establish a monopoly to control the spice trade.

Blaeu writes about the alliances between the island of Tidora and the Portuguese, and between the island of Ternata and the Dutch. These neighbouring islands, which he claims are ‘soo na by malkanderen, dat men met een grof-geschuts kogel van d’een kust de andere kan bereyken’ [so close to each other that a cannon ball fired from one coast will reach the other], were constantly at war with each other. Conflicts were mostly fought out at sea, with Moluccans using kora koras, a type of traditional outrigger canoe that is depicted on Blaeu’s map.

At the time of publication of the Atlas (1664), the Dutch East-India Company (VOC) had defeated the Portuguese and the Spanish, and had managed to establish a monopoly on the spice trade. Information about VOC-controlled territories, such as the Moluccas, was sensitive because it might give away potentially useful knowledge to competitors. What is noteworthy in this regard is that Joan Blaeu was the VOC’s official cartographer, which meant that he was basically bound to secrecy. This makes the inclusion of a map and a description of the Moluccas in the Atlas Maior highly unusual and deserving of further research.

Further reading:

Storms, M. “Geheimhouding bij de VOC? De dubbele petten van Blaeu en van Keulen,” Caert Thresoor, 38(1), pp. 14-25.